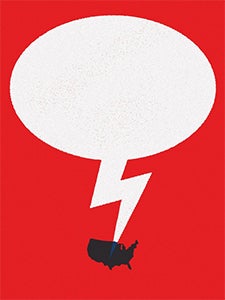

How did American politics lose its civility?

In 1800, Thomas Jefferson found himself in the political race of his life. Jefferson was running for president of the young republic and needed an edge in the election against John Adams, his friend turned philosophical and political foe.

Jefferson called on a journalist and pamphleteer named James Callender. He secretly funded Callender’s attacks on Adams, who was soon denounced as a hypocrite and warmonger. Adams, Callender declared, “behaved neither like a man nor like a woman but instead possessed a hideous hermaphroditical character.”

Adams and his supporters retaliated. They called Jefferson an atheist and seized on racist attitudes, dubbing him the “son of a half-breed Indian squaw.”

When the name-calling ended and operatives finally put down their quills, Jefferson won the election.

Fast forward 216 years, and the mudslinging tone of the presidential race sounds surprisingly familiar. During every presidential election cycle, pundits seem to utter the same declaration: “This could be the nastiest, bloodiest race we’ve seen in years.” Sometimes they’re right.

Alienation and anger

Over the last two decades, fundamental changes in the political landscape, global economy and technology have changed the tenor of politics. The pamphlets and journals of Jefferson’s day have given way to seemingly endless news and opinion outlets with political viewpoints. Discourse often descends into the rude and crude. Republican presidential candidates talk about the size of one’s hands — and its physical implications, nudge nudge — during a national debate. Supporters of a Democratic presidential candidate throw chairs and issue death threats over delegate counts in Nevada.

“Today, anybody can say anything and everyone has a channel,” said veteran political consultant Robert Shrum, Carmen H. and Louis Warschaw Chair in Practical Politics and professor of the practice of political science at USC Dornsife. “Senator Pat Moynihan once said, ‘Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.’ Now everybody has their own facts. You can go to the website you want, to the TV channel you want, and get the facts you want.”

Shrum has witnessed many of the highs and lows of campaign rhetoric during dozens of election cycles in American politics. He has steered campaigns for U.S. Democratic presidential candidates, congressional representatives, governors and mayors for the last 40 years.

He worked with Ted Kennedy in the 1980s when there were clearly strong philosophical and political differences between Republicans and Democrats. But he points out that there was a different tone then.

“Amid their differences, President [Ronald] Reagan and Kennedy worked together on immigration reform. Reagan and [Democratic house speaker] Tip O’Neill compromised on Social Security. Reagan would go out and have a drink with Tip O’Neill, and he could raise funds for the Kennedy Library,” Shrum said.

“Today, a lot of the pragmatism that I have seen in my political career has been driven out of the system. What I see politicians focusing on is not a series of programs and policies, but more on alienation and anger.”

Growing divisions and plunging trust

Data from the Pew Research Center seem to confirm a growing divide in politics: Democrats and Republicans have moved farther apart. In addition, Americans’ trust in government has plunged to new lows, according to national surveys.

During such uncertain times, people have a tendency to return to survival and coping instincts, says Jesse Graham, an associate professor of psychology at USC Dornsife whose research focuses on how ideology and morality interact to influence human thought and behavior.

“We are tribal by nature, and it’s very easy to turn that tribal switch on,” Graham said. “I think politics becomes a trigger for tribalism.”

From left, Carmen H. and Louis Warschaw Chair in Practical Politics Robert Shrum, Jesse Graham of psychology and Christian Grose of political science. Photos by (Shrum) Matt Meindl and (Graham and Grose) Peter Zhaoyu Zhou.

Graham points to a famous study by the social psychologist Muzafer Sherif in the 1950s. Sherif divided up a group of 11- to 12-year-old boys in an isolated, mountainous setting and gave the groups names: the Eagles and the Rattlers. The groups lived near each other, and each group was allowed to bond without contact with the other group. Then the experiment team introduced competition between the Eagles and the Rattlers. Baseball games quickly devolved into name-calling, the tribes vandalized each other’s camps, and soon they were ready to fight with rocks and sticks before the researchers stopped the violence.

Graham believes that the dynamics and dysfunction of the Eagles and Rattlers experiment can be seen in myriad tribes today — liberals versus conservatives, vaccination supporters versus anti-vaxxers, or the National Rifle Association versus the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, for example.

And the goals of the tribes center too much on attacking the credibility and character of the opposing tribe, he notes, rather than on getting along.

“If your goal is just obstruction and to stop the other side, that doesn’t lend itself to civility,” Graham said.

A path to reconciliation

So that raises the most important question during these contentious times: Do people from all of these tribes — Democrats, Republicans, Libertarians, biomedical researchers, environmentalists, climate scientists and climate change skeptics, just to name a few — have any chance to get along in the 21st century?

The USC Schwarzenegger Institute for State and Global Policy has done research on how two California reform measures reduced partisanship in the state. In 2008, California voters approved the creation of an independent panel to draw district lines. The goal was to end political gerrymandering, a practice that allowed elected officials to draw their own political district lines and ensure that districts would consistently be Republican or Democratic.

California voters approved a second significant reform in 2010 by ending the closed primary system — where only partisan voters could participate in primary elections — and replacing it with a top-two primary system. The top-two system allows all voters to participate in one primary, and the two candidates receiving the most votes, regardless of party, face each other in the general election.

Bonnie Reiss, global director of the USC Schwarzenegger Institute, and Christian Grose, associate professor of political science and a USC Schwarzenegger Institute faculty fellow, summarized the results of their research on these two reforms in a 2016 op-ed in the Sacramento Bee:

“The research shows a significant reduction in legislator ideological extremity, with a 34 percent reduction in the Assembly, and a 31 percent reduction in the Senate. This has led observers who once considered California ‘ungovernable’ to look at it as an example of what is possible when partisan polarization is reduced.

“We also conducted research outside of California that compared the outreach and messaging of candidates in states with closed primaries to those with open primaries and top-two primary systems. Here, too, the findings were significant. Candidates were more responsive to independent voters in both open and top-two primaries, and candidate messages to voters of the other party were more bipartisan in open primary states and even more so in top-two primary states.”

Find common ground

Dan Schnur, assistant professor of the practice of political science, still sees the possibility for civil discussion and positive political change during these complicated times — especially starting with young people. Schnur directs USC Dornsife’s Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics, where he helps students from across the political spectrum engage in government and public service, and teaches popular classes in politics, communications and leadership. With decades of experience as a political reformer and a leading political strategist and communicator, he has worked on issues ranging from redistricting to rebuilding the political center.

“At the Unruh Institute, we host 20 to 25 events a year that are designed to include a range of viewpoints and ideologies so our students understand different political perspectives,” Schnur said. “We ask people to explain what they believe without demonizing others. We want our students to understand that people who disagree with them are not stupid or evil — they just happen to have come to different conclusions and deserve respect.”

For Schnur’s colleague Shrum, this approach of teaching measured discourse, well-articulated arguments and agreeing to disagree is perhaps the only way forward. Shrum doesn’t see any neat, simple solutions to the current problems of political discourse. He doesn’t believe that civility can be legislated, and he knows there’s no way to control the accuracy of information as it filters through the internet, social media and the 24-hour news cycle.

For Shrum, it all comes back to the idea that individuals are capable of elevating the way they interact with others and taking responsibility for how they express their arguments. “I think we have to come back to Jefferson’s notion. The best answer to bad speech is good speech,” Shrum said.

Maybe focusing on common problems, rather than fixating on personalities and winning at all costs, is the most promising approach. The Founding Fathers did that. A decade after Jefferson and Adams battled bitterly for the presidency, they became friends and regular correspondents, returning to the intellectual high ground that represented the best of their political careers.

On Jan. 21, 1812, Jefferson wrote words to Adams that perhaps could inspire today’s politicos to opt for civil compromise:

“A letter from you calls up recollections very dear to my mind. It carries me back to the times when, beset with difficulties and dangers, we were fellow laborers in the same cause, struggling for what is most valuable to man, his right of self-government. Laboring always at the same oar, with some wave ever ahead threatening to overwhelm us and yet passing harmless under our bark, we knew not how, we rode through the storm with heart and hand, and made a happy port.”