USC Dornsife’s Viet Thanh Nguyen pens Time magazine’s cover story

“Love it or leave it.” Viet Thanh Nguyen, a Vietnamese immigrant who came to the United States as a refugee with his parents after the fall of Saigon in 1975, has heard this simplistic phrase with its underlying edge of menace countless times.

Nguyen, University Professor, Aerol Arnold Chair of English and professor of English, American studies and ethnicity, and comparative literature, has made the cover of Time magazine’s Thanksgiving edition with an essay on immigration that argues for a more nuanced, more inclusive vision of America that allows for the fact that criticism can coexist with a love of country.

Here, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Sympathizer (Grove Press, 2015) talks about what inspired his essay, why it’s so timely and how he feels about making the cover.

Did Time approach you or did you approach them?

Ben Goldberger, an editor at Time, asked me to write an essay on immigrants for their July 4 issue two years ago. I did that, and then he very kindly thought of me again for this Thanksgiving issue.

How do you feel about this honor?

It’s very gratifying because they didn’t tell me that it was going to get the cover, so it was a total surprise. Publishing in Time is very important, but I also think of it as a history. The Time cover is an explicit reference to all those Norman Rockwell paintings that also struggled with the idea of “What is America?” There’s a sentimental Rockwell, of course, but he was also trying to confront the challenge of an America that embraced all of its diversity, and we’re still dealing with that today. Some of the same issues of the 1930s and ’40s about confronting fascism and white nationalism versus a more inclusive America that would embrace all of us, but also would be an ideal for the entire world, are divisions we’re still dealing with today.

You wrote the essay in France. Did you find it helpful to be outside America when you wrote it?

Absolutely. I’ve learned a lot in France by confronting my own American ideas about race and diversity and nationality and talking to the French, who have a very different version of these kinds of ideas. It’s important for all Americans to have that kind of ability to step outside of our country because otherwise we just get wrapped up completely within an American set of assumptions. It’s always been crucial for me to think about what it means to be American outside of the United States.

You reflected on this for a long time. How long did it take you to write the essay in the end?

I thought about it for a few months and took a couple of brief stabs at it, wrote a few lines here and there, but it wasn’t working. Once the pieces in my mind clicked together, I wrote it in two drafts fairly quickly. It was really getting that idea of “Love it or leave it” as the opening line that really allowed me to frame the entire essay around this question of love — given my love for my son, the love of family and the love of country, and thinking about why some people would make this idea of love into an ultimatum. I would never want to do that. And so, once I knew that I was going to challenge that idea of ‘Love it or leave it,’ then everything fell into place.

What is the most important point that you want people to take away from your essay?

We live in a complex country with a complex history, and to say ‘Love it or leave it’ is a way of avoiding that complexity. It’s totally possible to love our country, whatever the country is, and understand its complexity and contradictions, as well. And I would argue that it is necessary to understand the complexities and contradictions of the country that we love, if we’re really, truly going to love these places.

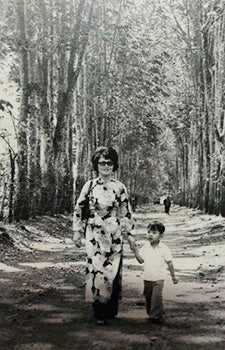

Viet Thanh Nguyen as a child in 1973, with his mother, Linda Kim Nguyen, in Ban Me Thuot, Vietnam. Photo courtesy of Viet Thanh Nguyen.

Your essay carries a very timely message for all Americans. Why is it so important?

We’re at a moment in our American history where there are two visions fighting for what this country means. One vision says we can get along with all Americans, everybody in this country. It’s an inclusive vision. It doesn’t matter who we are, where we come from, how long we’ve been here. Another vision that’s being put forth about this country says no, this country only belongs to a certain group of people, basically white people. That vision is exclusive. It says we need to guard this country, defend this country and keep people out. I just wish most people would understand that the other vision of the country, the one that’s inclusive, says they belong here, too. Everybody belongs. Those who have embraced that vision of a diverse and inclusive America don’t want to kick anybody out; they want everybody to evolve.

Do you think it is a question of love versus fear?

Yes, I do. The people who embrace the vision of fear love this country too, but they mix that in with fear and hatred, and they need to listen to the other people in this country, who I think are actually the majority, who say that love should not be undermined by fear and hatred.