In Memoriam: Philip J. Stephens, 71

Philip J. Stephens, professor emeritus of chemistry at USC Dornsife, who invented and developed two major techniques for characterizing molecular structure, has died. He was 71.

Stephens died July 31 in Los Angeles after a battle with a dementia-related illness.

In addition to being a brilliant chemist, Stephens was “fun, witty, adventuresome and a go-getter,” said his wife, Anne-Marie Stephens. “I shall always remember him as a loving, funny, irrepressible and generous companion, a talented musician, a man of impact in any company.”

In 2008, Stephens, then a USC Dornsife faculty member for more than 40 years, was named a Fellow of the Royal Society, the highest distinction given to a British scientist and the equivalent to the National Academy of Sciences in the United States.

In 2008, Professor Emeritus of Chemistry Philip J. Stephens was named a Fellow of the Royal Society. Here, he speaks during a ceremony at USC celebrating the honor. Photo by Melanie Stephens.

Stephens pioneered the use of two chiral spectroscopies — magnetic and vibrational circular dichroism (MCD and VCD) — and the application of advanced theory (density functional theory DFT) to ascertain the absolute molecular configurations of organic and biomolecules. Spectroscopy is the study of the interaction between matter and radiated energy, or light. Stephens applied the techniques he invented to study a diverse group of systems, ranging from heme proteins (red proteins that carry oxygen in the blood and have other important biological functions ) and blue copper proteins to the iron-sulfur complex in ferredoxin, a protein that transfers electrons.

The technical innovations Philip brought to the field of CD can be found in virtually all of today’s CD instruments. His technique has been applied in the pharmaceutical industry to determine drug structures, help calculate safe temperatures for accelerated stability studies and to screen for better formulations.

“Professor Stephens had a stellar career as an outstanding scientist, scholar and teacher,” said Chi Mak, professor and chair of chemistry at USC Dornsife, adding that Stephens served as chemistry department chair two consecutive terms, from 1992 to 1998.

“He was known for his administrative acumen and his charming sense of humor,” Mak said. “His many contributions to the department will be felt by generations to come.”

Charles McKenna, professor of chemistry at USC Dornsife, collaborated closely with Stephens in pioneering studies on nitrogenase CD and MCD. Most recently, McKenna worked with Stephens and Stephens’ long-time associate, Frank Devlin — a lecturer who oversees the spectroscopic instruments in the chemistry department — on an effort to detect chiral spectroscopic effects in phosphate ion made chiral by isotopic substitution. They were working together on a joint National Science Foundation proposal about new VCD research at the time Stephens became ill in late 2009.

“Philip was a very rigorous, demanding and ambitious scientist who did not suffer fools gladly,” McKenna said. “To those who knew him well, he could be a convivial and loyal friend, and showed a typically English sense of understated humor.”

McKenna recalled that Stephens would sometimes complain that his English friends claimed he had acquired an American accent.

“Since to American ears he retained a distinctly British accent, we joked that his accent was somewhere over mid-Atlantic, heading slowly west,” McKenna said.

Born in West Bromwich, England, in 1940, Stephens earned his Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Oxford. He studied at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark and the University of Chicago before joining the faculty at USC Dornsife in 1967.

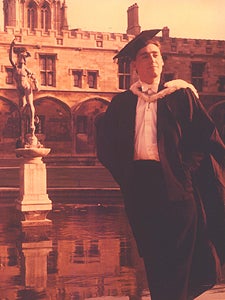

Philip Stephens at the University of Oxford on the day he received his bachelor’s degree. Photo courtesy of the Stephens family.

Stephens wrote more than 200 published papers across many areas of chemistry. He received the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellowship, the USC Associates Award for Creative Scholarship and Research, as well as a Guggenheim Fellowship.

In a “scientific memoir” article in Theoretical Chemistry Accounts in 2007, Stephens wrote about hiring in 1977 his then-postdoctoral fellow, Devlin, who had obtained his Ph.D. from University College Dublin in Ireland.

“This was one of the smartest things I ever did,” Stephens wrote. “Frank is a brilliant instrumentalist and he has been responsible for all of the instrumental developments in my laboratories from his arrival to the present time. I am deeply grateful to him for his work of the past three decades.”

Stephens and Devlin had been writing a book presenting a thorough analysis of VCD and the theoretical prediction of VCD. After Stephens became ill and the funding ran out, Devlin and theoretical chemist James Cheeseman completed the book, VCD Spectroscopy for Organic Chemists, published by CRC Press in June 2012.

“Philip dearly wanted this book to be finished and in print,” Devlin said. “James and I really wanted to complete it so we kept at it.”

Devlin said Stephens was a novel thinker who could quickly find the kernel of a problem.

“Philip was a true scientist,” Devlin said. “He wanted to pursue the research no matter the outcome. He strived to find the true answer to something even if it wasn’t what he expected.

“Philip had a talent for explaining difficult concepts — I will dearly miss our long and fruitful conversations.”

In 2008, Stephens reflected on his many breakthroughs.

“The thing that’s very important, is the great support of the chemistry department, the university and [USC Dornsife],” Stephens said then. “If they had regarded chemistry as an uninteresting and insignificant field and department, things would have been much more complicated.”

In addition to Anne-Marie Stephens, Stephens is survived by his daughter, Melanie Stephens.

The funeral is private. The Department of Chemistry is organizing an event in honor of Stephens to take place in Spring 2013.