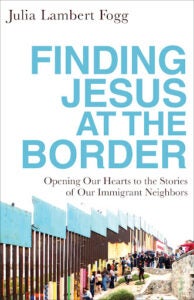

Finding Jesus at the Border: Opening Our Hearts to the Stories of Our Immigrant Neighbors

Rev. Julia Lambert Fogg, Ph.D. is a religion professor at California Lutheran University and the author of Finding Jesus at the Border: Opening Our Hearts to the Stories of Our Immigrant Neighbors.

Rev. Julia Lambert Fogg, Ph.D. is a religion professor at California Lutheran University and the author of Finding Jesus at the Border: Opening Our Hearts to the Stories of Our Immigrant Neighbors.

She is a panelist in the IACS event Neighbors at the Border: An ecumenical conversation about migration and immigration in Christian thought. The conversation will feature top scholars and be moderated by Religion News Service Reporter Alejandra Molina.

Rev. Fogg is ordained in the Presbyterian Church and serves on the board of The Abundant Table, a non-profit helping farmworkers in Ventura County.

IACS spoke to Rev. Fogg about her book Finding Jesus, and migration and immigration in Christian thought.

Q: Why did you write this book, and how did you find the powerful personal stories you include?

Rev. Fogg: Our neighbors in every direction all have powerful stories. The short answer is I wrote this book because Santiago, a college student of mine and a congregational leader, encouraged me to. He heard me speak and preach about the Bible and the stories of Jesus in ways he’d never heard before — ways that included and honored his experience in the world as a first-generation Mexican growing up in Southern California. Santiago and I worked closely together doing research. We created church programing that directly responded to the needs of the youth in the parish neighborhood. The stories of people I know in Finding Jesus are the stories of this neighborhood, those students and their family members and parallels between their lives and the scriptures. As I started writing the book, I also began visiting detention centers and accompanying local neighbors to their ICE check-in visits. I continue to work closely with farmers in Oxnard, Calif. for The Abundant Table and Farm Church.

Q: From a theological standpoint, what does Christianity teach us about immigration and migration?

Rev. Fogg: When I teach the Bible and immigration, my university students tell me that they’ve “never heard this in church” or, “didn’t know the Bible said that about Jesus crossing borders!” The Bible says a lot about immigration, migration, divided families, geographical, ethnic and religious borders and boundaries — we just haven’t read it that way, and we haven’t educated pastors and congregations to hear these words and stories from this perspective. Look, my interpretations aren’t “new” and I haven’t invented them. In many respects, they are thousands of years old — recorded in the very scriptures themselves. One way to see migration in scripture is to read the Bible with a map. Border crossing is fundamental to human movement, especially the movement of God’s people through economics, war, love and the building of households. I argue that migration is fundamental to the divine incarnation. In Finding Jesus I write about God’s incarnational commitment to cross the existential border between the divine and human. God literally becomes human to accompany us in our humanity and, in that act, shows us how to also cross borders to accompany our human neighbors on their journeys. We follow a God who migrates. God leads people out of slavery to cross deserts; Jesus leads people from the rural life of Galilee to the big city for profound prophetic and salvific work; God calls, sends and accompanies prophets, judges, apostles and disciples to meet and engage other cultures and peoples; God moves people like Paul, Ruth, Rahab and Phoebe across borders to build communities of care and compassion. Paul even calls these networked communities of care the Body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12).

For Paul, Christ’s body forms a network across the Roman Empire but gives allegiance and ultimate loyalty only to the Holy Spirit that animates Christ’s body. Christ’s networked body depends on the hubs of local house churches and the “spokes” of migrating teachers and traders who communicate between the hubs and unite the body in such a way that joy and suffering, resources and debts are shared (Philippians; Galatians; Romans). Christians serve a God who crosses borders through the incarnation and who shapes a living resurrection body of believers spread across the globe to serve and accompany one another “in Christ.”

Border crossing is fundamental to human movement, especially the movement of God’s people through economics, war, love and the building of households.”

Q: Scripture calls on us to love our neighbors and care for those suffering. Yet a 2018 Pew Research study found that the majority of white evangelical Protestants say the U.S. does not have a responsibility to accept refugees. Why is this the case and how can more people be drawn to Christian theology on immigration?

Rev. Fogg: It is possible that the Christian call to receive refugees — that is, to offer hospitality, or to care for one’s neighbor in the Matthew 25 movement — and the geopolitical secular responsibility of the U.S. to receive refugees may be two different questions. They at least may require different paths of reasoning. For example, I wonder if the same Christians who think the U.S. doesn’t have a political responsibility to receive refugees would at least agree that all Christians are called to offer hospitality by providing water, food or housing to those in need. Matthew 25 doesn’t restrict offering a cup of water only to those inside our national borders. And Matthew makes it very clear in Jesus’ birth story that at least one refugee family who fled the threat of violence held salvation in their hands for all of us — U.S. born or not. So reading the stories of scripture with Christians who disagree on U.S. responses to immigrants and refugees might develop some theological common ground in all of us to welcome immigrants.

But another theological path is to start with basic practices of hospitality in one’s own community. To commit first to developing habits of hospitality and to addressing need with one’s physical neighbors. And to continually expand one’s practice to include more neighbors, especially and critically including those who are different than us. As we expand our own theological borders to include more diverse neighbors within our own country, we may one day see our national borders, and the rights and restrictions they connote, much differently. Meanwhile, those who are called to work at the border with immigrants from outside, or in their neighborhoods to receive and sponsor refugees, are also practicing Christian habits of hospitality. We need both sets of work and practice.

As we expand our own theological borders to include more diverse neighbors within our own country, we may one day see our national borders, and the rights and restrictions they connote, much differently.”

Q: How have your experiences as a pastor in a bilingual church impacted your views on immigration and migration?

Rev. Fogg: Two ways. First, and this is why I wrote the book, crafting a message from the Gospel on a regular basis for a specific congregation of young people — many first, second and third generation immigrants — means I began to read Jesus’ stories differently. I began to see the parallels between Jesus’ life as a migrant child and the lives of the migrant families in my congregation. I listened to children in elementary school navigating multilingual homes, navigating multiple cultures — at school, in church and at home — while also trying to avoid the social bullying and pressures of local gangs. What was the gospel saying to them? A lot, it turns out.

Second, these young people and their families taught me what immigration concerns looked like on the ground: “Uncle so and so got deported.” “My grandmother passed away in Mexico and I never met her.” “I can’t go to college because I don’t have documentation.” “I’m afraid to visit relatives in Arizona because they are picking people up off the street and deporting them if they don’t speak English — whether they have papers or not.”

These are the daily effects of U.S. immigration policies on the ground from the perspective of families who are living them. Reading the Bible in this context is different than the experiences through which I read the Bible growing up. The stories of my Southern California congregation changed me.

Q: How can we create public policies that ensure the safety of U.S. citizens through secure borders, while simultaneously creating open pathways that welcome immigrants and refugees into our country and providing the support they need to achieve a better life?

Rev. Fogg: Many U.S. border towns have figured out a balance between security, the rights of citizens, and the economic and personal needs of visa holders, family members, shoppers and workers to cross the border regularly. The tricky part is developing such policies nationally to address the inconsistencies between, for example, our northern and southern borders, or outdated quota limits on specific countries. Another problem is the lack of legislative support for border crossing permits to fill the U.S. economic demand for a lower-paid, short term, and skilled work force (farming, poultry and pork processing, are examples of skilled and physically demanding jobs that are short on labor). Everyone agrees our immigration policies are in shambles. But there has been no political will from the top, or widespread support from the ground to change them. Understanding the issues is only a first step. Electing committed legislators who understand the issues and then supporting them to make needed changes from the ground up has to be a next step.

Q: How should Christians respond to the current migration crisis at the U.S. border?

Rev. Fogg: With open curiosity, compassion and a willingness to listen and act on behalf of neighbors in need. That is, we don’t know what others have gone through to get to our borders, or what laws govern our borders, unless we regularly ask and investigate. Our U.S. immigration laws are changing often and they are not clear to people on the ground traveling for months to get here. We cannot assume immigrants know the laws or have the possibility of waiting during the multi-year processes to gain access to the U.S. when they and their families are in acute need. The economic situations and the political contexts for immigrants are changing all the time. What holds true for one group does not hold true for another.

Christians need to investigate, ask questions and listen. If we feel called to help we can investigate further and find concrete ways to do so effectively. I offer multiple steps we can take to accompany migrants in Finding Jesus, as do many local immigrant assistance groups.

Editor’s note: Rev. Dr. Julia Lambert Fogg is a professor in the Religion Department at California Lutheran University in Thousand Oaks, Calif. She specializes in the New Testament, first century Christianity, theologies from the margins, border crossing narratives, and cross-cultural reading practices. She was named Professor of the Year by the CLU class of 2008.