Discovery

In 1933 archaeologists from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago found a large group of clay tablets and tablet-fragments in small rooms connected to the fortification wall at Persepolis, the palace complex founded by the Achaemenid king Darius I (522-486 BCE) in the heartland of the Persian Empire. The find spot gave its name to the find: Persepolis Fortification Tablets, an estimated 15,000-30,000 of them. The tablets are administrative records stemming from a single bureau of regional administration based at Persepolis; they were written in the middle of the reign of Darius I, about 509-494 BCE, and they thus record an administrative system that touched every stratum of Achaemenid imperial society, from the lowliest workers through bureaucrats and governors to the royal family itself.

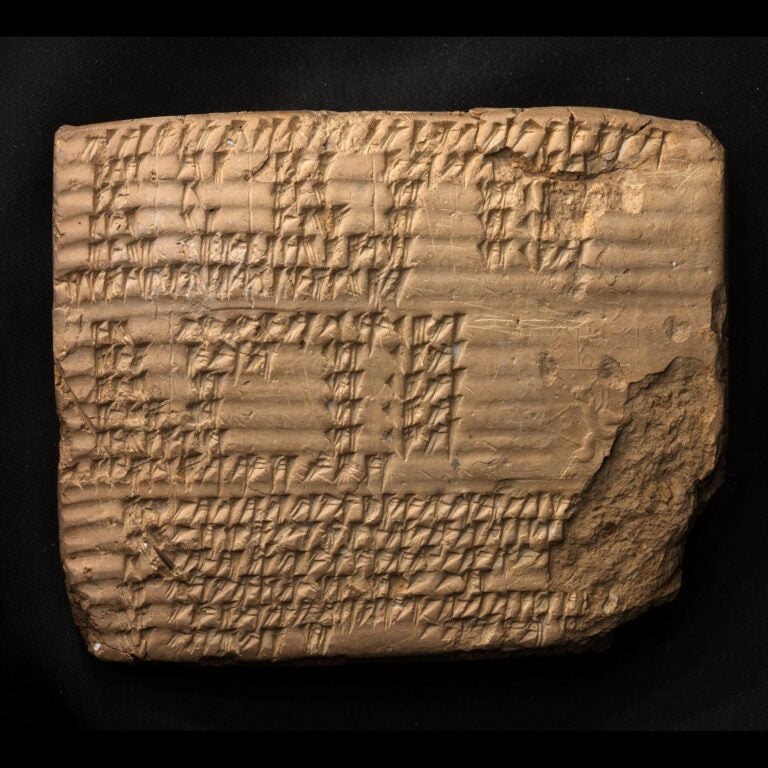

Description

The tablets fall into three main groups, according to script and language. Most (10,000 or more) are written in cuneiform script and Elamite language, in a dialect that abounds in words and names borrowed from contemporary Iranian languages. Some (600-1,000 or more) are written in Aramaic script and Aramaic language, again rich in evidence of Iranian. Others (some thousands) bear no text at all, but only impressions of one or more seals. These groups, interconnected by shared provenience, shared contents and shared seal impressions, were components of a single ancient information system that recorded in turn an ancient regional network of communication, interaction and administration.

Significance

In 1937 the tablets came to the OI on loan for study and publication. The Elamite tablets became the responsibility of Richard T. Hallock (OI). His publication of about 2,000 texts in 1969 transformed every aspect of serious study of Achaemenid languages and history. The Aramaic tablets—the particular focus of this proposal—fell to Raymond A. Bowman (OI). The significance of the Aramaic tablets is of two kinds: first, they will add an entirely new dimension to the study of the Fortification Archive and the administrative system that was long represented only by the Elamite records, a system that has provided new clues for a wide range of topics in the study of the entire Achaemenid empire; second, they supply a new corpus of Imperial Aramaic texts, of unparalleled contents and unmatched size, precisely dated, precisely provenienced and contextualized, with wide implications for the paleography, dialect, and history of Aramaic, as well as later Jewish and Christian cultures that employed Aramaic.

The Project

In 2007 the West Semitic Research Project and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (now the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures) began a joint project to digitally image a significant portion of the archive using high-end imaging technologies. An imaging lab was set up at the OI, and processing was carried out both at the OI and the WSRP at USC. In order to capture the ink inscriptions on the Aramaic tablets, they set up a view camera with a BetterLight scanning back and continuous lighting. To capture the Elamite cuneiform writing, as well as the seal impressions, over the several years of the projects two Reflectance Transformation Imaging domes were constructed, utilizing DSLR cameras and LED lights (See Our Technology—RTI).

For further information on the project, see Persepolis Fortification Archive.

Images from this project can be found on the following sites:

Article Categories

Non-Biblical Ancient Texts Relating to the Biblical World: Non-biblical inscriptions and documents from ancient times that improve our understanding of the world of the Bible.

Biblical Manuscripts: Images and commentary on ancient and medieval copies of the Bible.

Dead Sea Scrolls: Images and commentary on selected Dead Sea Scrolls manuscripts.

USC Archaeology Research Center: Images of artifacts from the teaching collection of the University of Southern California.