A Photographic Exhibition of Ancient Text and Artifacts of Biblical Times from the Archives of the West Semitic Research Project

For 40 years, the West Semitic Research Project (WSRP) of USC’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences has been photographing ancient texts from the biblical world. Directed by Emeritus Professor of Religion Bruce Zuckerman, a fellow of the Annenberg Center for Communication, WSRP’s team of scholars and technologists are generally acknowledged to be the world leaders in developing and adapting the most advanced photographic and computer imaging techniques for the analysis, decipherment, and dissemination of a wide range of texts from the ancient Near East. The West Semitic Research archive now consists of well over 1.5 million images of ancient texts, including, among others, the oldest alphabetic text yet discovered, ancient narratives of Canaanite gods and goddesses, dispatches sent to the pharaoh in Egypt from Jerusalem and neighboring cities, Aramaic documents of the Persian empire, Dead Sea Scrolls, early Coptic papyri and biblical manuscripts of both the Old and New Testaments. Through the USC Digital Library, high resolution WSRP images of some 250,000 ancient texts and artifacts are now at fingertip access to scholars, educators and students worldwide—with more being added to the image database on a regular basis.

Although the primary aim of the WSRP is to make technical photographic images that convey to scholars and students the clearest readings of ancient texts, the images themselves are frequently stunning stunningly beautiful—an exquisite mirror that reflects the artistic abilities of the scribes and artisans in biblical times. In the following series of selected photographs from the WSRP archives, some highlights are featured which show how the art of photography and the power of technology can work together to reclaim faint messages from a remote and ancient world that are both of scholarly importance and of great beauty.

(Updated from an Annenberg Exhibit in 2007)

First Jewish Revolt Year 3 Silver Shekel, USCARC 10534

Coin from the First Jewish Revolt, 68/69 CE. When the Jews revolted against Rome in the year 65 C.E., they minted their own coins as a symbol of their break from the Roman Emperor. This coin was minted during the third year of the revolt. The obverse (left) shows a Temple vessel, and the inscription “Shekel of Israel” in paleo-Hebrew, the archaic Hebrew alphabet. The reverse depicts pomegranates, and the inscription “Jerusalem the Holy.”

Photograph by Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research. Courtesy University of Southern California Archaeological Research Collection.

3Q15 Copper Scroll, Cut 15, Column 8

One of the Dead Sea Scrolls, written on copper, early 1st century CE. The Copper Scroll is unique among the Dead Sea Scrolls, being the only one inscribed in metal. The scroll was found in Qumran Cave 3, rolled up into two parts. The copper was so heavily oxidized that it had to be cut into twenty-three half-cylinder segments, rather than unrolled. The text lists a vast quantity of buried treasure. Unfortunately, after 2,000 years the directions for finding the treasure remain rather obscure. One paragraph in Column 8 reads, in Hebrew, “In the irrigation cistern of the Shaveh, in the outlet that is in it, buried at eleven cubits: 70 talents of silver.”

Photograph by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Department of Antiquities, Jordan.

Achaemenid Agate Cylinder Seal, Spurlock 1900.53.0052A

A cylinder seal from the Persian Period c. 5th-4th centuries B.C.E. This is a roll-out image, side view and seal impression image of a cylinder seal in the Spurlock Collection, showing three Magi, or Zoroastrian priests. Each Magus holds a bundle of sticks, and all rest upon a winged sun-disk. Note how the artist has used the pattern in the agate stone to form an apex with the sun-disk.

Photograph by Bruce Zuckerman, Marilyn Lundberg and Wayne Pitard, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

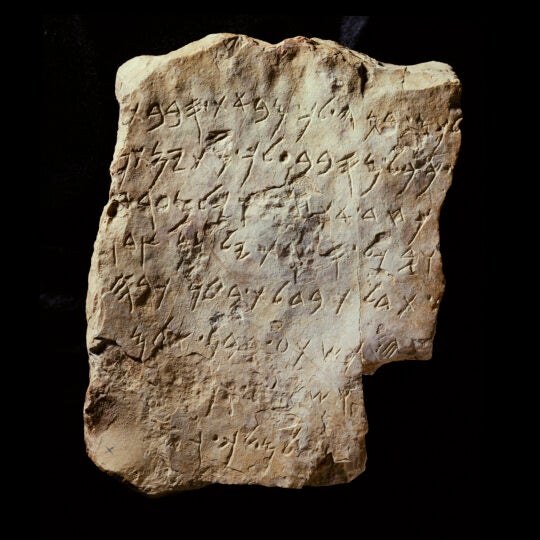

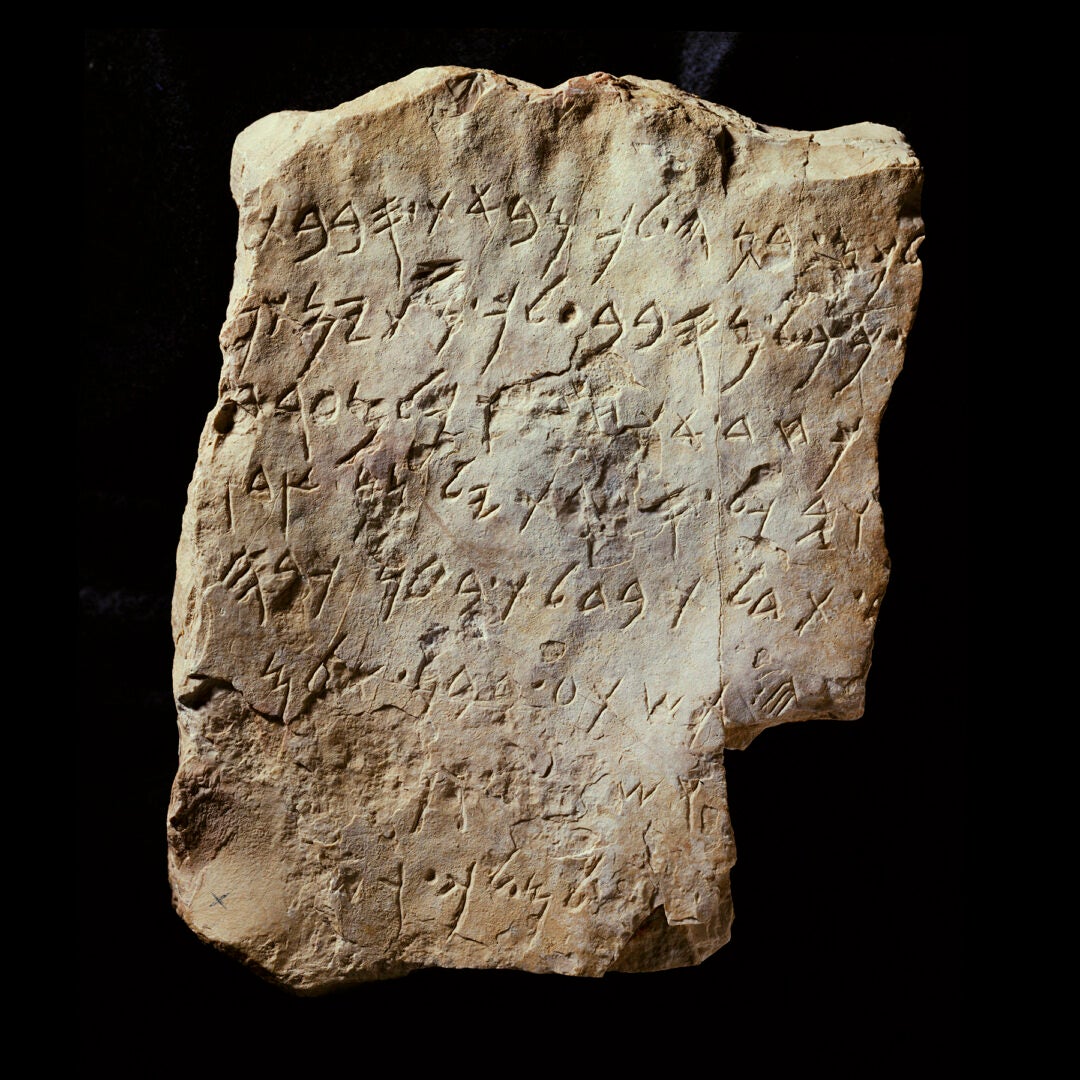

Amman Citadel Inscription, 9th c. BCE

The Ammonite inscription pictured here was found in the 1960s on the site of the Citadel, or fortress, of Amman, Jordan, ancient Rabbath-Ammon. It is generally believed to be a building inscription, of either a temple or the Citadel itself, although some have suggested that it is an oracle or instruction from the god Milkom, god of the Ammonites.

This is the most extensive text as yet discovered in the Ammonite language.

Photograph by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Department of Antiquities, Jordan.

Early Dynastic III Serpentine Cylinder Seal, Spurlock 1900.53.0112A

Cylinder Seal rollout from c. 2500-2350 BCE. Cylinder Seals are small objects carved from stone or shell, about the size of a AAA battery, up to a size D battery. They were used much like a signet ring in the Middle Ages, or a credit card today, in that they were rolled across clay tablets to verify a person’s participation in an economic transaction. In other words, they were the ancient equivalent of a signed charge card.

Photograph by Bruce Zuckerman, Marilyn Lundberg and Wayne Pitard, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

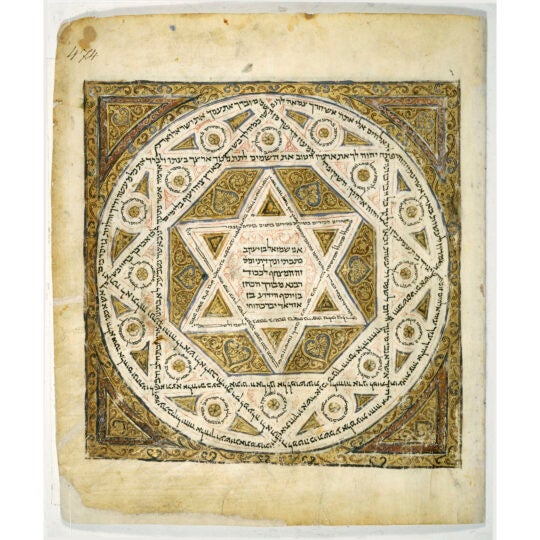

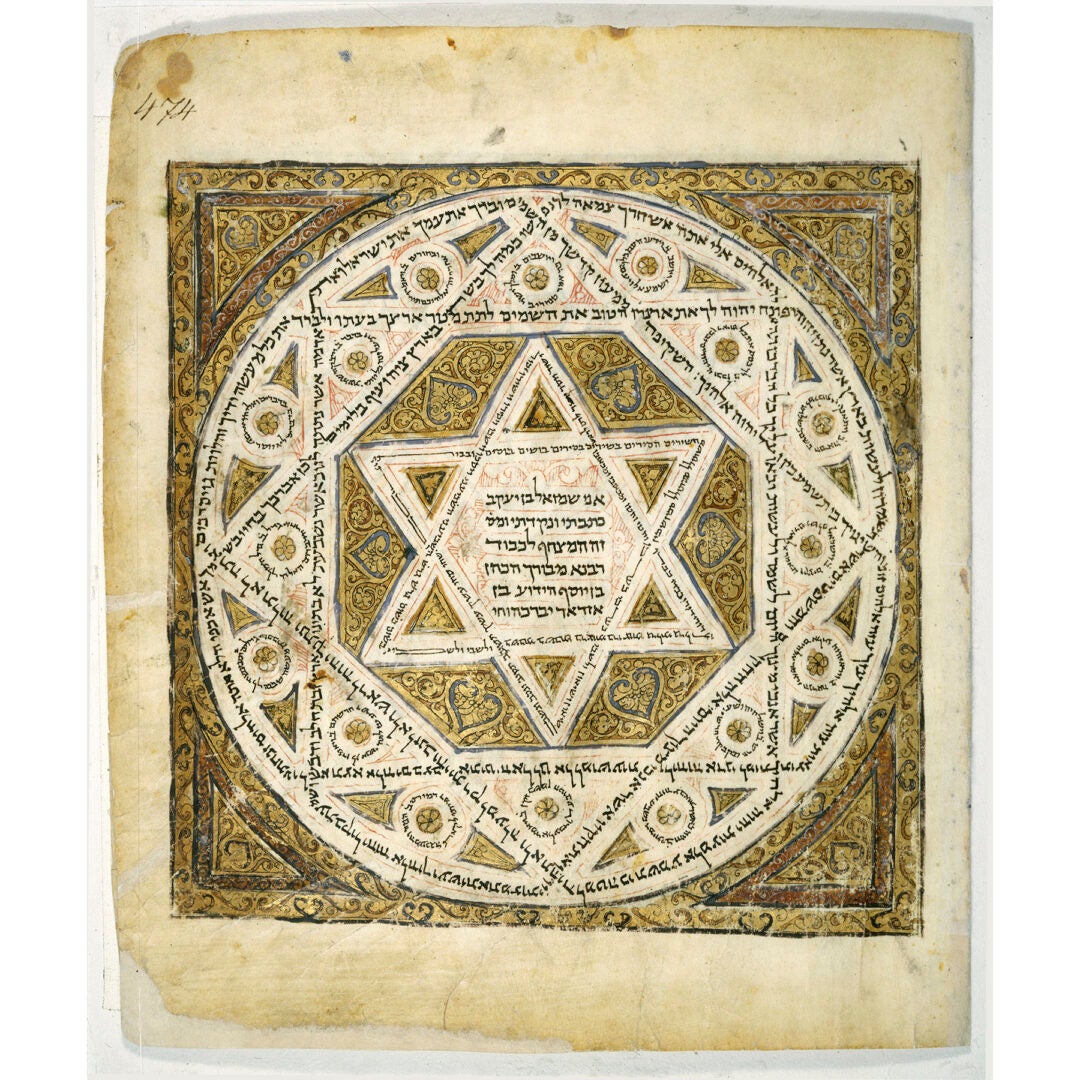

Leningrad Codex, Firkowitch B19A, folio 474a, c. 1008 C.E.

The Leningrad Codex is the oldest complete copy of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) still in existence. The manuscript was probably written in Cairo and was the prize manuscript in the collection of Abraham Firkowitch, who discovered and purchased it in the first half of the nineteenth century. He later gifted the collection to the Russian Imperial Library in St. Petersburg. The importance of this manuscript was first recognized by Paul Kahle, when he studied the manuscript after the Russian Revolution in the renamed Leningrad, from which the manuscript gets its more familiar name. Manuscripti “L,” as it is usually abbreviated, is generally recognized as the manuscript of reference for all modern Hebrew (Masoretic) Bibles today. At the end of this biblical text are sixteen “carpet pages,” illuminated pages that use verses from the Bible as part of the decoration. In the center of folio 474a is a Star of David. The text in the middle reads “I Shemuel the son of Ya`akov wrote and pointed and transmitted this manuscript for the honor of our blessed teacher the priest, the son of Yosef the sage, the son of Azdak, may the Living One bless him.”

Photograph by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research, in collaboration with the Ancient Biblical Manuscript Center. Courtesy National Library of Russia.

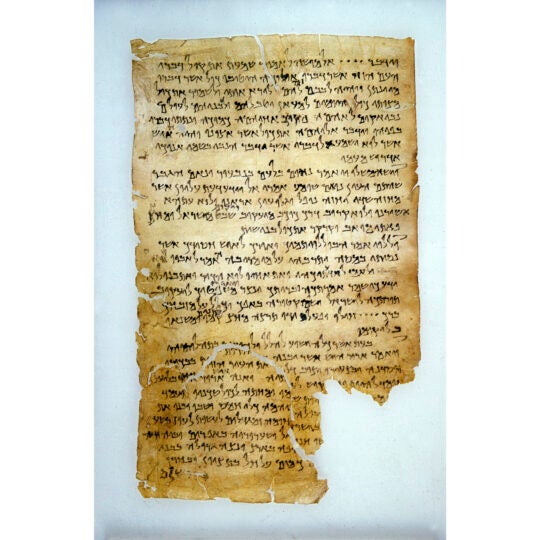

4Q175 Testimonia (or Messianic Anthology), middle 1st century B.C.E.

This Dead Sea Scroll text from Qumran Cave 4 text includes five biblical quotations in Hebrew connected by interpretation. The first two quotations refer to the raising up of a prophet like Moses. The third quotation refers to a royal Messiah, the fourth to a priestly Messiah. A quotation from Joshua is connected to the coming of a time of great disaster, brought on by those dedicated to evil. A “testimonia” is a collection of verses from the Bible, strung together to prove a point. Note that the scribe piously substitutes four dots for the letters that constitute the biblical God’s sacred name.

Photograph by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Department of Antiquities, Jordan.

Limestone Funerary Stele, from Marion, Cyprus, c. 480-420 B.C.E.

In this lovely funerary monument, a seated woman gazes at a bird that she holds in her hand. A Greek inscription in Cypriot Syllabary script: reads “I am Aristila of Salamis, daughter of Onasis.” The syllabic writing system shown here was widely used on Cyprus before being replaced by the Greek alphabet.

Photograph by Bruce Zuckerman and Marilyn Lundberg, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Department of Antiquities, Cyprus.

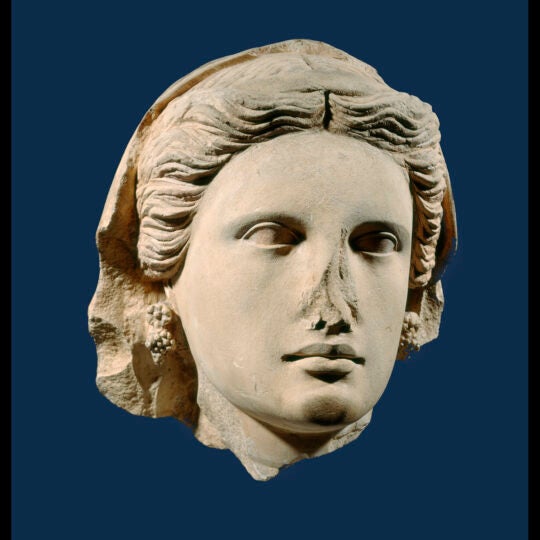

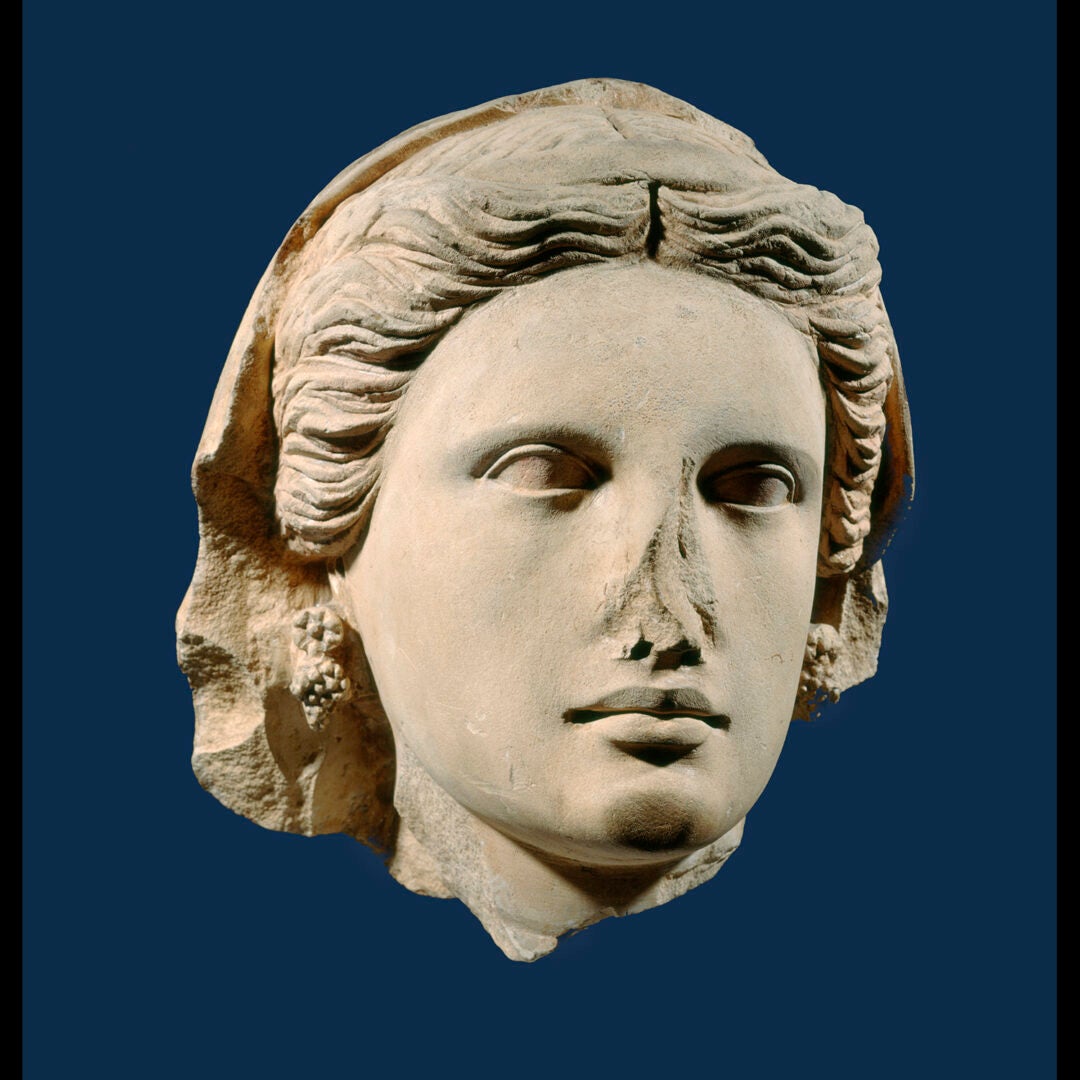

Head of a Woman from Arsos, Cyprus, c. 3rd c. B.C.E.

This beautiful portrait of a woman’s head is carved from limestone in a Hellenistic style and also comes from Cyprus. Because Cyprus served as the cross-road of the eastern Mediterranean, it reflects many cultures—Egyptian, Phoenician, Roman and, most especially, Greek.

Photograph by Bruce Zuckerman and Marilyn Lundberg, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Department of Antiquities, Cyprus.

Moabite Seal in Bronze Bezel, c. 8th century B.C.E.

Stamp seals, like cylinder seals and medieval signet rings, were used to seal and therefore verify economic transactions. Unlike cylinder seals (see nos. 2-5), stamp seals were more frequently employed to seal papyrus documents. In the ancient Near East, a contract or other document would be written on papyrus, rolled, folded, and tied with string. The participants in the transaction would all impress their seals in blobs of clay placed on the knots of the string to prevent the document from being changed. If the legal conditions of the document came into question, then the document could be unsealed and reviewed in front of a judge or a group of witnesses. The inscription on this Moabite seal reads “Belonging to Kemosh’u/or, literally, “Kemosh [=the Moabite’s patron god] is fire/light.” A four-winged deity stands in the middle.

Photograph by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research. Courtesy S. Moussaieff.

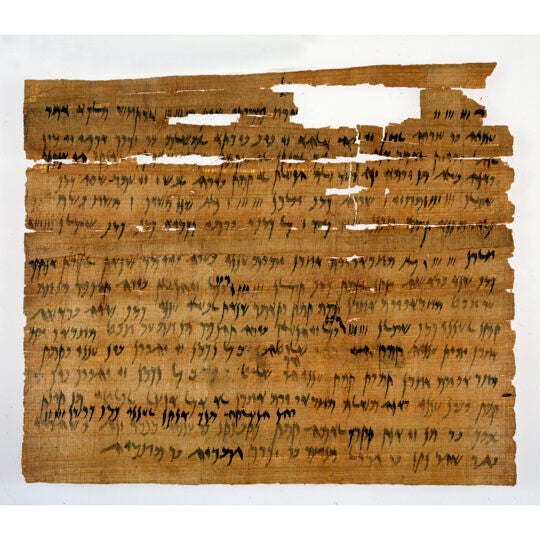

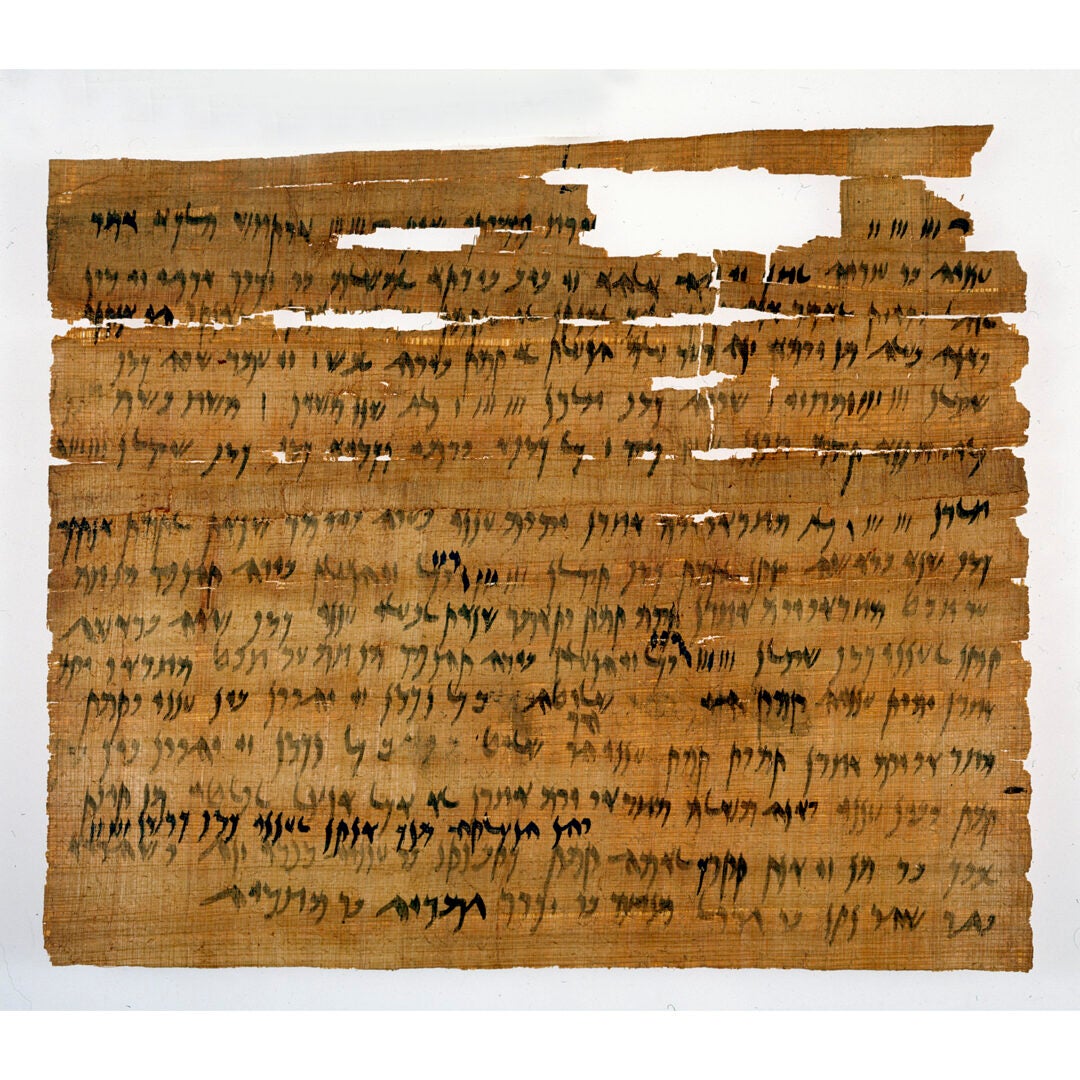

Jewish Aramaic Marriage Contract for the Marriage of Ananiah ben Azariah and the Handmaiden Tamut, Kraeling 2, BM 47.218.89, dated, August 9, 449 B.C.E.

In the late 19th century, a cache of papyrus documents from a private archive was found by farmers on the island of Elephantine, in the Nile River near Aswan, Egypt. Many other documents from a Jewish community in Egypt were later found by archaeologists in the same area. The Ananiah (or Anani) mentioned here was a priest of Yahu, the Aramaic version of Yahweh, the God of Israel. The document records his marriage with the slave of another resident of Elephantine. Note the writing between the lines and the erasures, indicating that negotiations were probably going on right up to the last minute!

Photographs by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum.

Egyptian Scarab Seals, Back and Face

The scarabs shown here are part of a collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art which were studied and documented by USC’s West Semitic Research Project. A catalogue of the collection was published by Johnna Tyrrell and Cara Cooney. The scarabs further served as the basis for a number of undergraduate research projects at USC, some of which received awards at the annual Undergraduate Research Symposium.

Top left: LM 86.313.27, Steatite Protection Scaraboid with Hippopotamus Back, “Amun-Ra, Lord,” c. 664-332 B.C.E.

Top middle: LM 50.4.7 (17-18/18), Faience Scarab, King worshipping solar boat.

Top right: LM 86.313.42, Steatite Protection Scarab, “Amun is Protection,” c. 1550-1069 B.C.E.

Bottom left: LM 50.4.5 (5-8/8), Faience Royal Name Scarab, “Thutmosis IV,” c. 1550-1069 B.C.E.

Bottom middle: LM 50.4.7 (3-18/18), Faience Protection Scarab, Symbols of Rejuvenation, Kingship and Afterlife, c. 1648-1540 B.C.E.

Bottom right: LM 50.4.5 (3-8/8), Faience Royal Named Scarab, “Thutmosis III, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands,” c. 1550-1069 B.C.E.

Photographs by Johnna Tyrrell, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

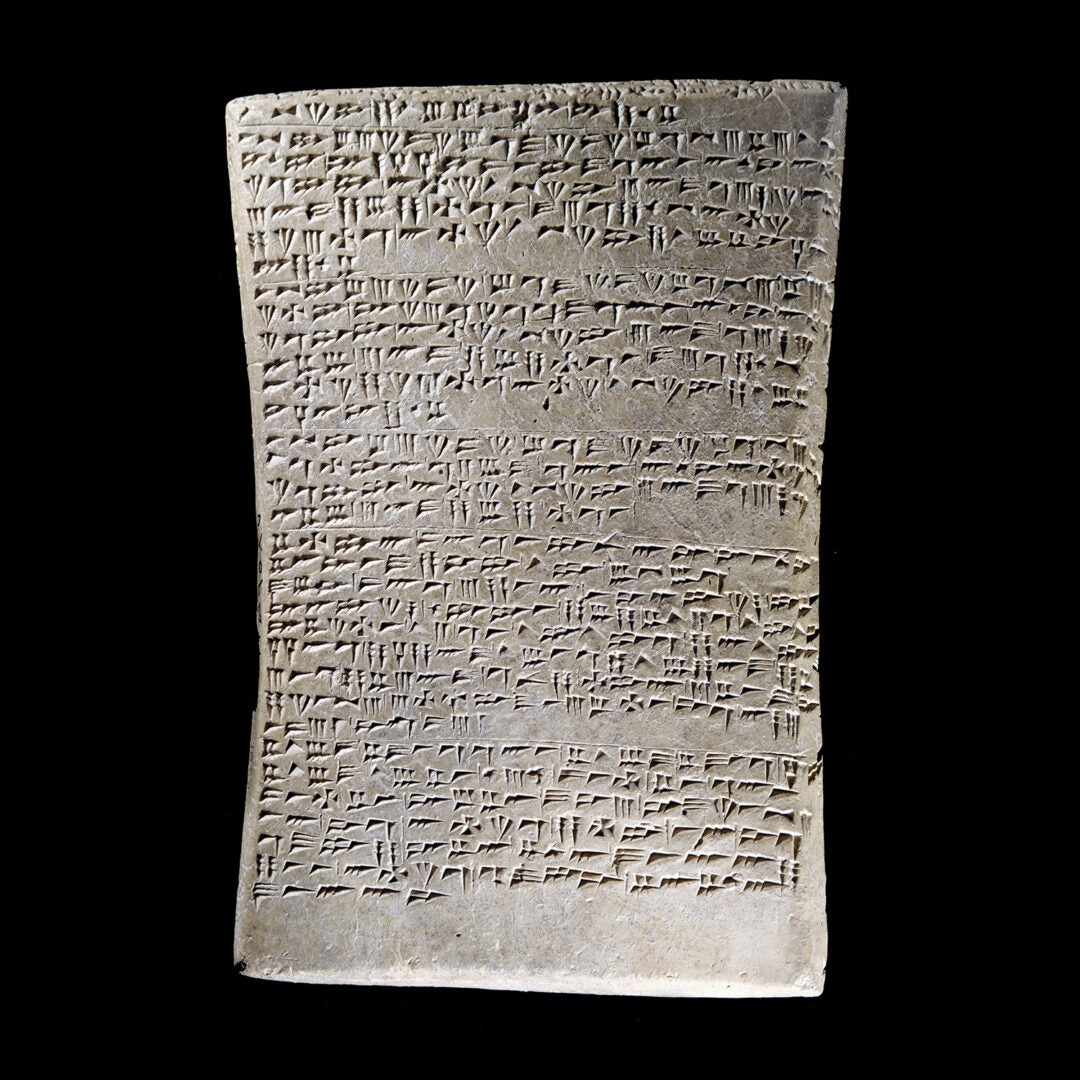

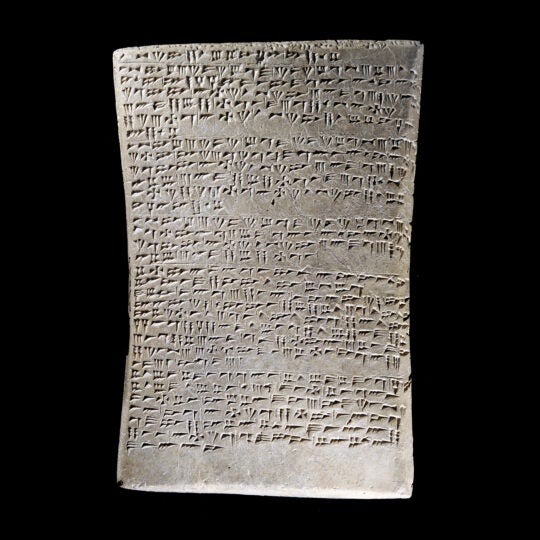

Snake Bite Incantation, KTU 1.100, c. 1400-1200 B.C.E.

An alphabetic cuneiform tablet from ancient Ugarit, this text was excavated at Ras Shamra on the coast of northern Syria. Although the writing system looks like Mesopotamian cuneiform (wedge-shaped characters), it uses only thirty or so characters to represent consonants in a language related to ancient Phoenician and Hebrew. This is one of a number of images of the Ugaritic corpus made by West Semitic Research as part of a joint research project between USC and the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign.

Photograph by Wayne Pitard, West Semitic Research. Courtesy Mission de Ras Shamra and the Department of Antiquities, Syria.