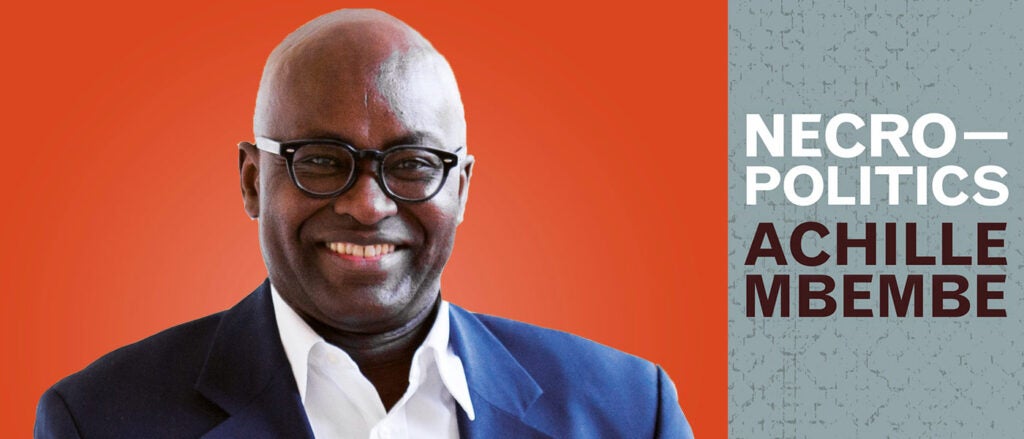

Professor Achille Mbembe, born in Cameroon, obtained his Ph.D in History at the Sorbonne in Paris in 1989 and a D.E.A. in Political Science at the Institut d’Etudes Politiques (Paris). He was Assistant Professor of History at Columbia University, New York (1988-1991), a Senior Research Fellow at the Brookings Institute in Washington, D.C. (1991-1992), Associate Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania (1992-1996), Executive Secretary of the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) in Dakar, Senegal (1996-2000). He was also a Visiting Professor at the University of California, Berkeley (2001), at Yale University (2003), at the University of California at Irvine (2004-2005), at Duke University (2006-2011) and at Harvard University (2012). He has been awarded numerous awards including the 2015 Geswichter Scholl-Preis, the 2018 Gerda Henkel Award and the 2018 Ernst Bloch Award.

A co-founder of Les Ateliers de la pensee de Dakar and a major figure in the emergence of a new wave of French critical theory, he has written extensively on contemporary politics and philosophy, including On the Postcolony (University of California Press, 2001), Critique of Black Reason (Duke University Press, 2016), Necropolitics (Duke University Press, 2019) and Out of the Dark Night. Essays on Decolonization (Columbia University Press, 2020).

ABOUT THE MASTER CLASS

Above: Achille Mbembe speaks with students in Professor Adrian De Leon’s AMST 680; November 11th, 2020 – University of Southern California

Building on the legacies of both Franz Fanon and Michel Foucault, Mbembe wrote his essay on Necropolitics in the aftermath of 9/11 and the Gulf War. Foucault defined the idea of Biopolitics as that which lets live and lets die (passively, sometimes through neglect), but Mbembe argues that we need to pay attention to Necropolitics, defined as that which makes live and makes die, engaging with the more active sense of the right to kill. He argues that the ultimate expression of sovereignty lies in the capacity to bring an end to life.

Colonial expansion began when Europeans were developing rules for war and ideas of legitimate violence, but the laws developed to apply within Europe were not applied to the colonies, where slave owners had a right to end the lives of their slaves.

His more recent work looks at developing a decolonial ethic of care, and the need to repair all life which is “in common”, both human and non-human. Classical humanism positions itself as defending humanity against all of non-human life, but at this point we need to go beyond classical humanism to look at preserving life in more than one species (our own).

He argues that new forms of governmentality have emerged which are based on ideas of government by negligence or abandonment, as some peoples are defined as not counting, being in excess, and so their worth is discounted.

He recently published an essay on “The Universal Right to Breathe”, inspired in part by the killing of George Floyd. In it, he argues the breathing is a relational category, both intangible and corporeal. To communicate is to share breath, but also—in the age of Covid-19—possibly to contaminate others. The forests of the Congo are the planet earth’s second “ecological lung” (after the Amazon) and the trees within these forests are vital objects, cared for by the people who live in these forests. Deforestation can be seen as a slow form of death along multiple scales and amplitudes.

Symbols, including African art objects, are vital resources which communities need to orient themselves in the world. Many of these art objects were looted during the colonial period, and they are now exhibited in ethnological museums and in the Vatican, as trophies of conquest or evangelization. Violence and extraction underpin this capture, so one form of the necropolitical targets those objects.