The Pedagogy of “Learning How to Learn”

Last Tuesday, I started my classes by asking my students to write for ten minutes about their feelings about the end of the semester. What would they remember, after the semester ended? What were they looking forward to most, after finals?

To my surprise, many of them brought up the activity in their one-on-one conferences with me later that week. “It’s crazy to think I’ve been going to college a whole year, and I’ve never even been to campus,” one of my freshmen said. Nearly all of them said they were looking forward to being a “real” college student—living in the dorms, sitting in lecture halls, socializing with friends in McCarthy Quad. An entire year of online learning had also taught them a thing or two about resilience.

“I never really take the time to think back on how far I’ve come,” another student confided.

I chose this journaling exercise, and others, as a means to help students process their feelings about the past year. Some questions I’ve asked in recent weeks include:

- When you look back on this moment ten years from now, what will you remember?

- How has the pandemic changed the way you perceive the world, and others?

- What life skills will you take away from this year of remote learning?

The writing and subsequent discussion provided a space for students to connect with each other and reflect on their experiences—the good along with the bad—and many of my fall semester students later cited the journaling prompts as one of their favorite aspects of the course.

Yet it’s also worth noting that reflective writing isn’t solely diaries or journals. In fact, reflective (or “self-reflective”) writing encompasses a wide variety of writing tasks, such as:

- reflective essays

- fieldwork reports

- freewrites

- self-assessments

- peer feedback

- logbooks (science fields)

- reflective notes (law)[1]

The more guided forms of reflective assignments typically involve having students deliberate on their own learning processes, and by so doing, develop their problem-solving and critical reasoning skills (or what is sometimes informally called “learning how to learn”).

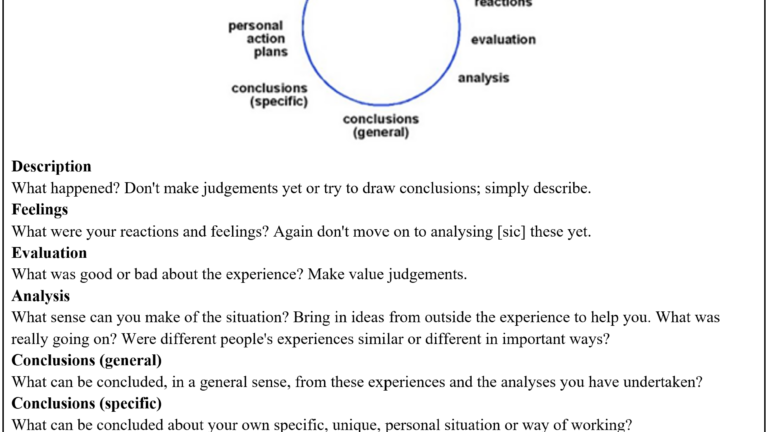

Interestingly, much of the current appraoches to reflective practice are indebted to the foundational work of Graham Gibbs, whose Learning by Doing (1988)generated a step-by-step method for build students’ self-awareness during experiential learning activities. This is now widely known as Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle (shared below, for your reference):

In this method, a student is asked to move through the steps one at a time, reflecting on an experience (or a simulated experience, such as a role play). It forces them to slow down—to not simply record an experience, but learn how to think critically about what occurred and make a plan for next time. This can be especially useful in healthcare and fields with an experiential component.

I do a similar kind of instructor-guided reflection after providing written feedback in my writing and critical reasoning courses. After reading over all of my written comments, students are asked to evaluate their own strengths and weaknesses as writers and respond to my written comments. Much like Gibbs’ “personal action plan,” students must then generate a plan for improvement on the next writing project.

In the decades since the publication of Learning by Doing, reflective writing has become a cornerstone of the student-centered classroom, and for good reason. It is adaptable to many different fields and teaching contexts. It can take whatever form is needed to serve each instructor’s particular learning objective. It can also, as it did in my classes, bring a challenging semester to a close with some deep thought and cautious optimism for the year ahead.

[1] “Examples of Reflective Writing.” University of New South Wales (UNSW) Sydney, student.unsw.edu.au/examples-reflective-writing