Why asbestos litigation won’t go away: Because asbestos won’t go away

It is tempting to dismiss asbestos as a problem of the past. The height of its consumption was in the 1970s, and asbestos litigation began over a half century ago. Many of its leading manufacturers and mining companies are long gone.

Yet asbestos litigation is back in the news.

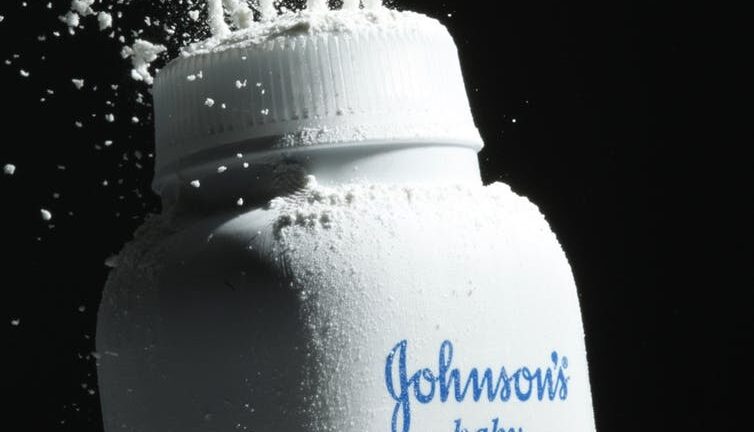

A trial court ordered Johnson & Johnson in July 2018 to pay US$4.69 billion for failing to warn customers that its baby powder contained asbestos, which naturally occurs in talc. The company now faces thousands of these suits, and its stock took a nosedive in December 2018 on a report that it knew its talc was contaminated. The company plans to appeal and continue to fight these cases, but, even if it eventually wins, their emergence raises the question: Why does asbestos litigation persist?

I have studied asbestos for decades and written books about its dangers and public policy around it. The issues surrounding asbestos or the material itself will not go away.

Stronger than steel, and potentially lethal

One reason for the persistence of the problem is that tons of asbestos remain in our communities, a legacy from when asbestos was prized for its remarkable commercial properties. It is a fiber made of rock that is stronger than steel, yet flexible enough to be woven into cloth. It is waterproof, corrosion proof and fireproof, as well as abundant and easy to mine.

Manufacturers found ways to add asbestos to everything from hair driers to battleships, roof shingles to children’s modeling clay, car parts to missile silos. Asbestos is still used legally in the U. S. for some purposes, despite efforts to ban it completely, like many other countries, including those in the European Union, Australia and dozens more.

Scientists now know that exposure to asbestos’ fibers can be lethal, causing a number of fatal diseases including mesothelioma, an aggressive cancer of the lining of organs, and asbestosis, a progressive scarring of the lungs. Asbestos exposure can also cause pleural plaques, fibrous thickenings of the membrane around the lung. This condition is asymptomatic and may not develop into serious diseases. But those who have been exposed face years of uncertainty because many of the worst asbestos-related diseases can take decades to appear.

And, yesterday’s asbestos can be today’s health hazard. Because it is a mineral, asbestos does not evaporate, and its dangers do not diminish over time. If anything, some asbestos products can become more dangerous as they become brittle and likely to release fibers into the environment.

Asbestos fibers can also be released when disturbed, a fact tragically illustrated by the Sept. 11 terrorists attacks when the collapse of the World Trade Center towers released a cloud of dust containing asbestos.

Finally, asbestos is part of the landscape of some communities, and epidemiologists have found higher rates of asbestos-related cancers in areas that are known to have deposits of asbestos-containing rock.

Accordingly, even if the U.S. followed the lead of other countries and prohibited its use, health risks from asbestos would continue. Consistent with this assessment, the World Health Organization reported that asbestos-related deaths have persisted worldwide, including in countries that banned it in the early 1990s.

Lawsuits, a result of politics?

A final reason for continued litigation is political. Asbestos is a global problem, but the American response has been distinct. Whereas other countries have addressed asbestos injuries through centralized benefit programs that pool costs and risks, the U.S. has relied much more heavily on litigation.

Consider the Netherlands. During the 1970s and 1980s, Dutch workers suffered five to 10 times the incidence of asbestos-related diseases compared to American workers. Dutch law allows workers to sue their employers for workplace injuries, yet there were only 10 asbestos-related lawsuits in the Netherlands in the 1990s. During the same period, one in three of all civil cases filed in the Eastern District of Texas were asbestos-related.

Dutch workers did not file lawsuits because they did not need to. They enjoyed much more comprehensive health and unemployment benefits, which were deducted from any recovery in the courts.

American workers also did not sue at first. Instead, they sought relief from state workers’ compensation programs. But these programs were designed to compensate workers for traumatic injuries, like broken arms and legs, and not slowly manifesting occupational diseases, like mesothelioma and asbestosis. As a result, these programs offered very limited relief.

With no relief, lawyers moved in

Entrepreneurial lawyers stepped into the breach. Aided by favorable rulings and the discovery of decades of corporate efforts to conceal the risks of their products, asbestos litigation took hold and ramped up. By the early 2000s, an estimated 730,000 claims had been filed targeting over 8,400 companies in 75 of 83 categories of economic activity within the U.S. economy. Building on their early successes, lawyers created an extensive infrastructure to support these claims, giving rise to a cottage industry complete with extensive marketing campaigns and sophisticated strategies for finding new claims. The final price tag has been estimated at over $325 billion in today’s dollars.

Initially, this litigation illustrated the heroic side of the American legal system: its flexibility, innovativeness and ability to take on powerful interests. Over time, however, serious concerns emerged from lawyers, policy experts and judges about its costs and fairness. Numerous studies demonstrated that administrative costs of asbestos litigation gobble up over half of all compensation paid. These costs might be tolerable if asbestos litigation has delivered consistent and timely compensation to victims, but payments have been erratic and slow.

Meanwhile, claims now are often herded into massive settlements or bankruptcy compensation trusts, where compensation varies and claimants are offered little, if any, individual due process. Even worse, asbestos litigation has reportedly become plagued by questionable practices and accusations of fraudulent practices that displace consideration of those suffering the most and unfairly burden the courts and businesses.

Given these problems, judges, interest groups and members of both political parties have repeatedly begged Congress to create a national asbestos injury compensation fund along the lines of other economically advanced democracies. These efforts have all failed at the federal level for a variety of complex political reasons, which have thwarted compromises over who pays, how much and to whom.

As a result, the erratic beat of asbestos litigation will continue, as the problem of asbestos will not go away on its own. People without adequate health insurance and social benefits will continue to suffer, and lawyers will continue to find ways to bring claims. Just ask Johnson & Johnson.![]()

Jeb Barnes, Professor of Political Science, University of Southern California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.