USC students help train lawyers to better represent detained immigrants

By now we have all seen the distressing news images of immigrant children separated from their parents and detained in cages at the southern border.

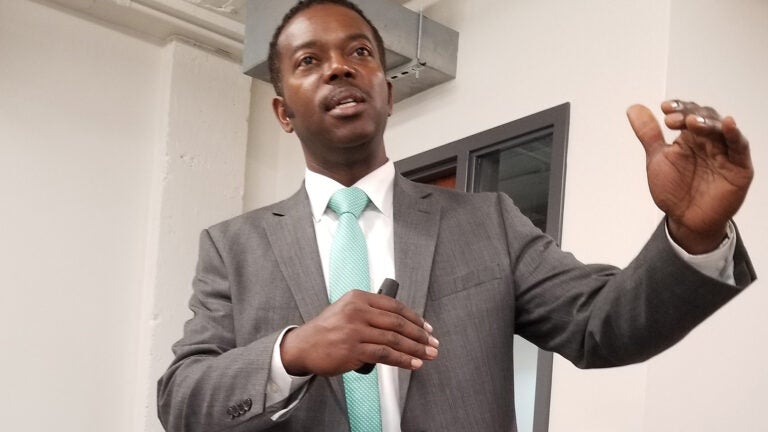

This August, Olu Orange led a group of USC students to South Texas to help train immigration attorneys representing these detained children and families. This was the third such trip to the border Orange has organized for USC students to enable them to support the efforts of those helping immigrant families — trips that are made possible by endowed funds from the Harding and Chaudhry families.

“Our first trip, in May 2018, was inspired by seeing the news of children being detained in dog-kennel type cages,” said Orange, who leads USC Dornsife’s Trial Advocacy Program. “Our second trip, taken in mid-August 2018, was inspired by accounts of parents having their children stripped from them. In both cases, the collective thought process of students in our program was, ‘This is wrong, and we need to go do something about it.’ So, we did.”

On their second trip, Orange’s team assisted with locating and identifying the detention status of more than 100 children around the country, many fleeing abuse or gang violence at home.

“Now those children may be provided legal representation and services,” Orange said.

After last year’s success, program students were enthusiastic to make a third trip to the border this summer. The eight-strong student team came from diverse USC majors including political science, psychology, computer science and philosophy.

A chance to double success rates

The group stayed in Harlingen, Texas, from Aug. 2 to 8, splitting their time between three projects.

First, the team went to Port Isabel Detention Center in nearby Los Fresnos to observe proceedings involving detainees at the border. There they met with attorneys from the South Texas Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project (ProBAR) — a joint project of the American Bar Association, the State Bar of Texas and the American Immigration Lawyers Association. Led by Orange, the USC students provided training and exercises to the ProBAR lawyers representing detained children and families.

Orange’s team designed and delivered presentations on various aspects of advocacy that the lawyers could use during further proceedings, such as ensuring opportunities to cross-examine government witnesses and attacking stereotype-based gang inferences. They also organized mock deportation hearings so the ProBAR attorneys could practice and fine tune aggressive federal court litigation tactics to get access to immigrant detainees’ information, which nearly doubles attorneys’ chances of success.

This summer, Orange’s team tripled the number of ProBAR attorneys who participated in the program, bringing the total to 22.

The attorneys found working with the students invaluable, Orange said, adding that USC is the only university in the country to undertake litigation preparation work with ProBAR.

“The attorneys really embraced our program and saw the value in it,” he added.

“All these kids that go down to South Texas from USC go with a purpose. They’re going because they want to have an impact. They want to change things. And they look up to these lawyers who are down there working so hard to do the best they can in this situation.”

Olu Orange with the USC students who traveled with him on his most recent trip to the southern border to help train immigration attorneys representing detained immigrant children and their families. From left, Elisa Herrera, Yvette Lopez, Anika Gidwani, Orange, Leana Ter-Martirosyan, Stepan Petrosyan, Pauline Roth, Marilyn Aguilar and Dylan Specht.

Emotional reunions

The team also volunteered at the Humanitarian Respite Center at Sacred Heart Church in McAllen, Texas, providing services, clean clothing, food and toiletries to newly released detainees and helping them gain a foothold on skills they will need to be successful as they take the next steps on their journey.

“For some parents, it was their first opportunity to know where their children were and to see them again,” Orange said. “They were tired, distraught, but hopeful because they had just been released. It was, for many people, their first opportunity to really breathe freely and know that they were safe.”

While the USC team weren’t allowed to see the detention conditions at Port Isabel, Orange said the people they saw who had just been released were not in good condition.

“For many folks, it was their first shower in 3,000 miles because those types of things were not available at the detention centers, and people told us that,” Orange said. “Some people had been detained without basic hygiene products and showers for weeks.”

Legal abuses

Orange and his student team found a situation where the law is constantly being changed to make the situation as difficult as possible for lawyers and their clients.

“Every time the attorneys representing detained children and families make strides to effectively represent them, the Trump administration changes the rules of the game to make it more difficult for anyone to be released or even have a fair hearing,” Orange said. “The hearings are not fair and the lawyers are facing constantly moving goal posts.”

Orange says he saw a degradation in the legal situation compared to last year.

In many cases, Orange noted, the courts are flouting detainees’ right to due process by denying them the right to legal representation and proceedings in their own language.

Also, people seeking asylum in the United States because they are fleeing death in their own countries are no longer able to petition safely for asylum from inside the country.

Working with ProBAR, the students conducted a research survey of law in Texas and Mexico and of American Bar Association ethics laws to determine the feasibility, as well as a methodology, of providing asylum services across the border.

Bearing witness

Yvette Lopez, a computer science major at USC Viterbi School of Engineering and program participant, described many heartbreaking cases the students witnessed while in Texas, including a deportation hearing for a Kenyan-Somalian man seeking religious freedom in the U.S. after he had been persecuted for converting to a different religion and preaching it in public in his home country.

“This man was bawling on the witness stand as he talked about how his sister was raped and murdered for their religious beliefs,” Lopez said. “He spoke of being tied up and burned with cigarette butts, leaving scars on his back that still exist today.”

Although they witnessed a lot of pain, Lopez said the students also met many people who gave them hope.

“The attorneys at ProBAR are fighting to their last breath to ensure that migrant children are getting the representation they need to navigate a hostile legal system,” she said.

When Orange suggested a more aggressive approach to trial, the attorneys implemented it and made it a success, Lopez said.

“When the team did presentations on making objections and delivering examinations, they were engaged and asked us hard questions,” she added.

“Their passion is contagious.”

Our best hope

Orange says he thinks students are society’s best hope of a backstop against the current backwards slide on human and legal rights at the border.

“Involving students in hands-on opportunities to see just how horrible things are for less fortunate people involved in unimaginable circumstances prepares them to not only stop the backwards slide, but to push to bring humanity back to where it should be in terms of having genuine appreciation and respect — and I’ll go so far as to say an affection — for other humans,” he said.

“I think this experience does that better than anything else could.”