‘Thou Whoreson Zed! Thou Unnecessary Letter!’

Although Shakespeare is famous for his cerebral language, USC College’s Bruce Smith wants his students to absorb the Bard with not only their minds — but their entire bodies.

The Dean’s Professor of English believes there is such a thing as over-thinking Shakespeare.

His teaching philosophy echoes Isabella, when she tells Angelo in Measure for Measure, “Go to your bosom, knock there and ask your heart what it doth know.”

Formerly of Georgetown University, Smith joined the College as part of its Senior Faculty Hiring Initiative in 2003. He’s interested in reintroducing the aesthetic experience in Shakespeare.

With a joint appointment in the USC School of Theatre, the Shakespeare scholar’s students read plays then interpret the works through written papers and live classroom performances.

In his undergraduate English 430 course, his students deconstruct the four major components in dramatic performance: body, space, time and sound. They read and together attend Shakespeare plays.

Then they act out scenes in class, or produce a video of their performance to show, or perform Shakespearean-inspired music. One student did a gymnastic interpretation of Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Carrying out these myriad forms gives students a chance to understand Shakespeare from the inside out.

“It’s their bodies that are doing it, it’s their voices, their sounds, their space, their time,” Smith said. “It’s more of an interior reaction. It’s not just something you see outside yourself, it’s something that becomes part of yourself.”

Smith, an early modern English literature and culture expert, teaches a university-wide undergraduate elective housed in the College that draws students from engineering to business. Called, “Body, Poetry, Self,” the course requires each student to perform work from a living poet.

“In some way, they have to put the poems across,” Smith said. “They can dance it, draw it, in a few cases they have cooked it.”

At times, students select a poet of their same ethnic background, then bake cookies or a dish representing the country, treats classmates can enjoy during the performance.

Smith also teaches in USC’s Visual Studies Graduate Certificate program for Ph.D. students throughout the university whose scholarly work focuses on visual culture — an important aspect of Smith’s own research.

He became hooked on the world’s preeminent dramatist after watching his plays. Becoming a theatergoer was accidental.

Bruce Smith’s most recently published book, The Key of Green (University of Chicago Press, 2008), looks at the color green from Shakespeare’s “green-eyed monster,” to the “green thought in a green shade” in Andrew Marvell’s The Garden.

Growing up in Mississippi, he completed his undergraduate degree at Tulane University, where he was accepted to a study abroad program in England. If he chose to study English, he would attend the University of Birmingham. If he chose psychology, he would be sent to the University of Hull.

“I got out a map and saw that Birmingham was 100 miles from London and Hull was over 200 miles from London, so I chose Birmingham,” Smith said. “As it turned out, that was a key decision because the University of Birmingham has the Shakespeare Institute.”

Living only a few miles up the road from Stratford-upon-Avon, Smith was able to attend Royal Shakespeare Company productions.

“My interest in Shakespeare had to do with it being a live proposition in theater,” Smith said. “It’s a different way of knowing Shakespeare than reading text.”

Smith is constantly encouraging his students to experience Shakespeare with all of their senses.

“I try to shake people up and try to get them to look at language in a different way,” he said.

In his forthcoming book, Phenomenal Shakespeare (Wiley-Blackwell, Dec. 2009), an original examination of Shakespeare’s staying power, he considers Shakespeare in American Sign Language. Watching Shakespeare through a language of gestures rather than words can bring out a more visceral response. He also considers accessing Shakespeare through Braille.

One chapter examines the intrinsic reflexes of audience members watching Shakespeare, especially violent scenes. In King Lear, for example, Gloucester’s eyes are plucked out of his head and crushed on the floor.

In such scenes, audience members may feel as if their own bodies are being touched, in this case their eyes, Smith said. He backs up his argument with a 2007 study in Science. In experiments with virtual reality, the journal said, subjects watching a projected image of their own bodies being tapped on their backs could feel tactile sensations in the same area.

“People who think about the power of Shakespeare think about power of language. I don’t deny that,” said, Smith, former president of the Shakespeare Association of America. “But I’m interested in seeing how the power of language is actually cuing the bodies on stage to do certain things and the bodies in the audience to feel certain things.”

There are other ways to enjoy the aesthetic experience and that is through color, Smith said.

His most recently published book, The Key of Green (University of Chicago Press, 2008), looks at the color green from Shakespeare’s “green-eyed monster,” to the “green thought in a green shade” in Andrew Marvell’s The Garden. In a unique cultural history, the book considers the significance of the color green in the literature, visual arts and popular culture of early modern England.

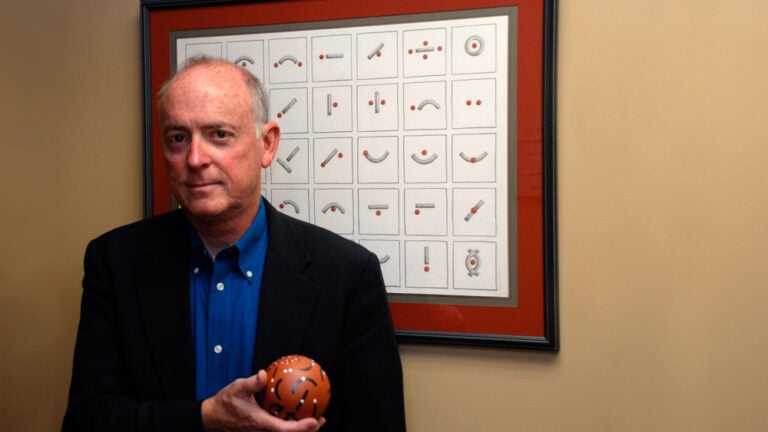

Emphasizing to his students they don’t need only words to appreciate Shakespeare, Smith shows them a different kind of alphabet. Called the spatial relations alphabet and created by artist Dana Chodzko, this alphabet is a series of black lines and curves with red dots, each representing a preposition. “Nouns and verbs can be overrated,” he said.

“This is a way of getting people off the page,” Smith said, holding in his hand a red clay ball painted with the same preposition alphabet. “I try to shock people into giving up their tacit assumptions.”