Tariffs: What are they, who pays for them and who do they benefit?

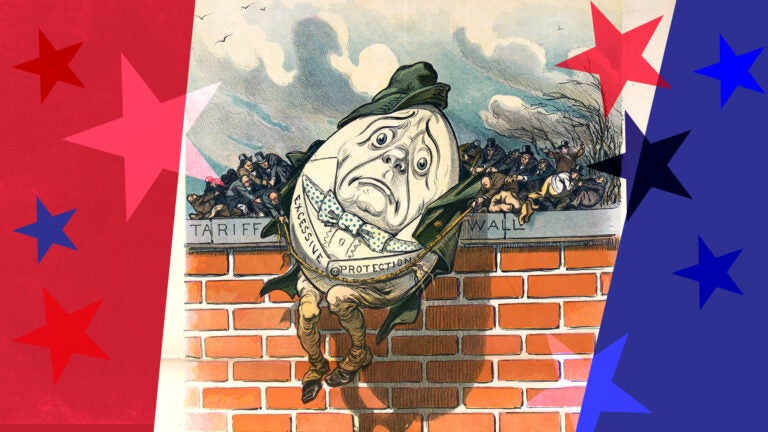

The United States government first implemented tariffs shortly after the Constitution’s ratification to help fund the young nation’s government. Over time, these taxes on internationally traded goods largely fell out of favor, only to resurface between World Wars I and II before fading again. Recently, tariffs have once again emerged as a favored policy tool, sparking debate over their impact and effectiveness.

Monica Morlacco, assistant professor of economics at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, recently answered questions about tariffs, including how they work, who they benefit and who pays the price for them.

What is a tariff and what is its function?

A tariff is a tax placed on goods when they cross national borders. The most common type is an import tariff, which taxes goods brought into a country. There are also export tariffs, which are taxes on goods a country exports, though these are rare. The United States does not allow export tariffs; the Constitution (Article I, Section 9) forbids them.

Tariffs are typically imposed for protection or revenue purposes. A protective tariff increases the price of imported goods relative to domestic goods, encouraging consumers to buy from local producers, who are thus “protected” from foreign competition. A revenue tariff, on the other hand, is mainly used to generate money for the government.

How long have tariffs existed globally, and more specifically, in the U.S.?

Tariffs have been used for centuries. In the U.S., they have been in place since 1789, with the first major tariff law passed to help fund the new government.

Over time, the importance of tariffs as a source of government revenue has declined, particularly in wealthier countries. For example, in 1900, tariffs accounted for more than 41% of U.S. government income, but by 2013, that number had fallen to just 2%. However, many developing nations, like the Bahamas and Ethiopia, still rely on tariffs for a significant portion of their revenue.

While the revenue-raising role of tariffs has diminished, they have made a comeback for protectionist purposes, often being imposed temporarily to shield specific industries or address trade imbalances. In 2018, for example, the U.S. imposed several waves of tariffs on specific products, sectors and countries, raising import tariffs from an average of 2.6% to 17% on more than 12,000 products.

Who has the power to authorize a tariff?

In the U.S., Congress has the power to set tariffs. However, under specific laws, the president can also impose tariffs, particularly in cases involving national security or in economic emergencies.

Who pays a tariff and who benefits from it?

In the U.S., it’s the importer — the company or entity bringing the goods into the country — that pays the actual tariff to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, part of the Department of Homeland Security. This payment occurs when the goods enter the country, though the true financial impact extends beyond the initial payer.

The impact of a tariff depends on whether the country imposing it is “large” or “small” in terms of its ability to influence world prices.

Generally, economists define a “large open economy” as one whose demand or supply can influence the world price of a good. Conversely, “small open economies” cannot influence global prices.

For instance, Vietnam, while geographically small, is the third-largest exporter of coffee. Its trade policies can significantly affect global coffee prices, making it a large open economy in that market. In contrast, a sprawling country like Russia plays a relatively minor role in global coffee imports and exports, meaning it has little effect on world coffee prices, classifying it as a small open economy with respect to coffee.

When a large open economy imposes an import tariff, several effects follow. Consider the example of the U.S. imposing a tariff on coffee imports:

- Higher prices for imported coffee: The price of imported coffee rises, making it more expensive for U.S. consumers and businesses, such as coffee shops.

- Terms of trade gain: Because the U.S. is a large open economy, the tariff can reduce the world price of coffee. Foreign producers, like those in Vietnam, may lower their prices to retain access to the large U.S. market. This price reduction, known as a “terms of trade gain” for the U.S., ensures that the domestic price of imported coffee does not rise by the full amount of the tariff.

- Reduced trade volume: Lastly, the total volume of coffee traded decreases. Higher prices reduce U.S. demand for imported coffee, and foreign producers end up selling less coffee, causing a decline in worldwide coffee exports.

If a small open economy imposes a tariff, the effects are more straightforward. Foreign producers have no incentive to lower their prices, since the small economy’s demand is too insignificant to affect the world market. As a result, the price of the imported goods rises by the full amount of the tariff. Moreover, the overall trade volume decreases just as in the case of a large economy, but without any terms of trade gain.

Who is adversely affected by a tariff and how?

In a large open economy such as the U.S., the effects of a tariff are mixed. Consumers, both individuals and businesses, are negatively impacted by higher prices. However, the domestic industry protected by the tariff, such as U.S. coffee producers, benefits by being able to sell more of their product. The government also benefits by collecting additional revenue from the tariff.

The overall effect depends on whether the benefits, like terms of trade gains, outweigh the losses from changes in production and consumption patterns. If the terms of trade gains are larger than the negative effects, the country can benefit. If not, the overall effect is a loss. For a small country, there are no terms of trade gains, so tariffs generally result in worse outcomes by raising prices and reducing trade.

The effects described above assume that everything else remains constant, meaning only the tariff in a specific sector changes. However, an important factor to consider is that when a country imposes tariffs on other nations, those nations often retaliate by imposing tariffs of their own — so-called “retaliatory tariffs.” These can compound the direct effects by reducing access to foreign markets and raising prices for other goods.

This is exactly what occurred in 2018 when the U.S.. imposed tariffs, prompting retaliatory tariffs from China, the European Union and others. In total, these retaliatory actions affected around $121 billion of U.S. exports, escalating the negative impacts beyond the original tariffs.

Any recommended reading for those who want to learn more about tariffs?

A helpful reference on the subject is the book International Economics: Theory and Policy by Paul R. Krugman, Maurice Obstfeld and Marc Melitz. Another well-regarded text is International Trade by Robert C. Feenstra and Alan M. Taylor.

For a deeper analysis of the costs associated with the 2018 U.S. tariffs, The Economist’s article “Who Pays for Tariffs?” offers valuable insights. [Editor’s Note: This article may require a subscription.]