The 2,300-year-old philosophy of Stoicism finds a foothold in modern times

In 2012, Penguin Random House sold 12,000 copies of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, reflections influenced by the Ancient Greek philosophy Stoicism. In 2019, the book sold 100,000 copies.

YouTube channels devoted to “Modern Stoicism” have millions of subscribers, and Silicon Valley tech millionaires expound its wisdom. What prompted a 2,300-year-old philosophy to stage a comeback in such spectacular fashion?

It may be that Stoicism’s ancient framework for managing emotions feels particularly relevant for navigating modernity’s crises. Our phones buzz ceaselessly with alarm about rising authoritarianism, the threat of nuclear war, or AI’s impending takeover, yet responding constructively to all of these disasters feels impossible.

Enter Stoicism, which urges you to ignore the rage bait, put down the phone and think more constructively. “Men are disturbed not by things, but by the views which they take of them,” says the Stoic Epictetus in his Handbook.

“Stoics think that each of us are finite, limited beings. There are a few things we can control and other things we can’t control, and we should keep track of those things and have different attitudes towards those domains,” says Ralph Wedgwood, director of the School of Philosophy and professor of philosophy at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “That’s the goal of life, to have this accurate understanding, and to be guided by this.”

Stoicism: The phoenix philosophy

Stoicism was born from disaster and has rerisen, rather Phoenix-like, for centuries. Around 300 B.C., a shipwreck bankrupted a merchant named Zeno and landed him in Athens, Greece. There, he began studying philosophy, eventually developing and teaching his own. He held forth at the Stoa Poikile, a columned walkway from which his acolytes, Stoics, would later draw their name.

For nearly 500 years, the philosophy held great influence in both Greece and the Roman Empire. It was eclipsed over the years by other branches of philosophical thought, and then Christianity. A millennium passed, and Stoicism became mostly forgotten, the vast majority of its texts lost or destroyed, including those of Zeno. (Most of what remains is Roman like the Meditations.)

In the 15th century, the Renaissance’s renewed interest in classical antiquity sent excited scholars diving into the archives to dredge up older ideas. One of these was Stoicism. The debut of the printing press in the 1440s made broad distribution of ideas easier, and Stoicism gained a more permanent cultural foothold, although its popularity would continue to wax and wane over the years.

Although Stoicism’s ascendance seems relatively recent, it’s actually been a somewhat steadily growing, subliminal influence since the 1970s.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a form of talk therapy that encourages patients to rethink their emotional reactions, was directly inspired by Stoicism. Its founder, the psychiatrist Aaron Beck, told an interviewer in 2007, “I also was influenced by the Stoic philosophers who stated that it was a meaning of events rather than the events themselves that affected people.”

CBT is now one of the most popular forms of mental health treatment. Small wonder, then, that Stoicism’s popularity has grown alongside the widespread clinical use of its philosophical relative.

Stoicism as a tool for the warrior scholar

However, unlike traditional therapy, which often conjures up visions of pastel couches and comforting Kleenex, Stoicism has a reputation for tactical, mindful hardiness.

Aurelius wrote down his reflections while planning military campaigns. Navy Officer James Stockdale famously deployed its teachings to help him endure years of torture and imprisonment during the Vietnam War. Stockdale turned in particular to the lectures of Epictetus, who himself suffered as a slave in ancient Rome.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that its current revival has sprung up in large part from the “manosphere” of male podcasters, YouTubers and Substack writers, an association that has some poo-pooing its revival as just a toxic return to repression of male emotions.

Wedgwood, whose USC Dornsife courses include “The Ancient Stoics” (PHIL 416), says that’s an inaccurate understanding of the philosophy. “It’s not about tamping down feelings. For Stoics, it’s about achieving an emotional intelligence, trying to change your habits so they’re not so destructive,” he says.

Stoics criticized emotions like anger, which they regarded as misleading. They analogized the beginnings of anger to being splashed with cold water, the jolt of which makes you feel you must immediately react. “This is an illusion, that somehow revenge would fix the wrong,” says Wedgwood. “Rather than raging or fuming, you should try to have feelings that are productive. We should think of the future rather than avenging the past.”

Women will find the philosophy’s wisdom just as useful; Stoics themselves made a number of egalitarian arguments, observes Wedgwood. “The later Stoics are not social reformers, but they believed women should receive the same education as men and insisted they have the same capacities as men for courage, wisdom and self-control.”

Stoics offer “circles of concern” to guide priorities

In addition to better management of emotions, Stoics offer helpful insight into how to prioritize demands on our time and resources, says Wedgwood. Such a framework may be increasingly helpful in an era in which we’re grappling with how to best respond to the crises of the entire world.

Consider the debate over rebuilding Notre Dame: Effective altruists decried the millions spent to fund the reconstruction of the Notre Dame Cathedral, arguing that the money would have been better spent on lifesaving mosquito tents in Africa. In recent discussions around immigration, Vice President JD Vance revived St. Augustine’s notion of “Ordo Amoris” (“Order of Love”) as a guide to how we deploy our attention and resources.

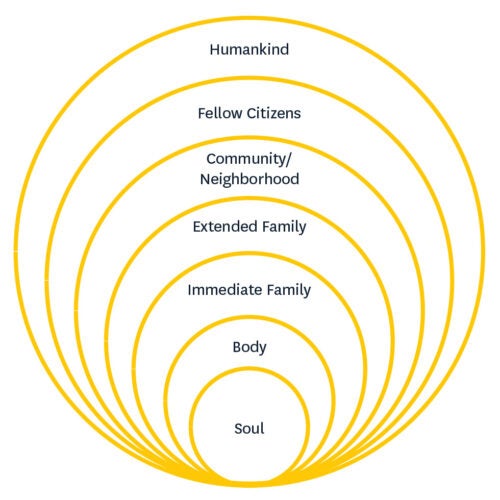

Stoics have been contemplating the best way to order our priorities since Zeno himself. They proposed that humans inhabit a nested set of circles, a framework of affinity dubbed “Oikeiosis.” The innermost circle was our soul, next came one’s physical body, then various layers of family, after that one’s community, and so on, to the entirety of humankind.

Closer circles are usually given more weight, but those closer to the edge of the ring can still be valued. We may even strive to collapse some of the difference between outer circles at times by treating them as if they inhabited a more inner ring. “For the Stoics, we do not belong to just one whole, we are part of many wholes, called to serve all those many communities,” says Wedgwood.

Recommended reading on Stoicism

For those interested in reading more Stoic philosophy, Wedgwood recommends:

- The Stoic Life: Emotions, Duties, and Fate by Tad Brennan

- Stoicism (Ancient Philosophies) by John Sellars

- Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience by Nancy Sherman

Becoming a Stoic requires reading about more than just Stoicism, adds Wedgwood. “The Stoic ideal is acquiring a reliably accurate understanding of the world.” Hence, the ancient Stoics studied a wide range of topics, from formal logic to theology to physics — all available for study at USC Dornsife.