Mind Your Language

Most teachers and parents will tell you that certain words prove more challenging to pronounce for a child learning to read.

Jason Zevin explains why. Take the word pint. If young Scarlet is familiar with the words “hint,” “mint” or “lint,” the first time she attempts to read the word “pint,” she will likely pronounce it to rhyme with the similar words she knows.

“Your experience with words that are spelled similarly to the words you’re trying to learn gives you a pretty good guess about how they’re pronounced, unless they’re something really unusual, like hors d’oeuvres or colonel,” said Zevin, associate professor of psychology and linguistics at USC Dornsife.

“Even if you guess wrong, you might get close enough and be able to self-correct.”

Zevin, a cognitive neuroscientist, joined USC Dornsife’s faculty in Fall 2013. He studies how people learn to read and speak, specifically how the brain’s architecture responds to what language is being learned. His research focuses on the similarities and differences between English and Chinese speakers.

“The question is: Are profiles of reading difficulty across languages the result of different brain organization for those languages?” Zevin said.

Or, could it be that readers have the same brain organization, but because the structure of the language is different, the problems for learning one language might be different in another?

“Those are some of the questions we’re working on.”

Zevin recently completed a sabbatical in Beijing where he worked with scientists at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Beijing Normal University in collaboration with the Haskins Laboratory in New Haven, Conn. He studied whether computer models using the same cognitive architecture — behavior learning patterns — to learn to read in English and Chinese could work despite the differences in the languages.

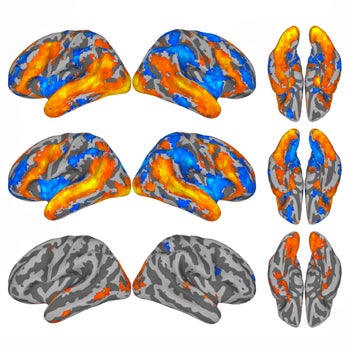

In Beijing, Zevin and his colleagues also observed the brain functions of study participants as they read fairy tales in English and Chinese while functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data were collected. The scientists compared images of the brain when the same phrase was read by a Chinese-language reader and an English language-reader.

Jason Zevin and his colleagues observed the brain functions of participants as they read fairy tales in English and Chinese. Magnetic resonance imaging data showed that very similar patterns of brain activity are engaged by reading across languages (top and middle images). Image courtesy of Jason Zevin.

They found that the underlying network in the brain of each speaker looked somewhat different — but not as different as expected.

“They seem to be differences in degree, rather than in kind,” Zevin said.

Zevin’s research also looks at speech perception, the process by which the sounds of language are heard, interpreted and understood.

At USC Dornsife, he will use neuroimaging to study how the age at which one learns a second language influences their ability to perceive and recreate nuances in the sounds of that language. For instance, how do English-speaking college students learning a second language differ from children learning a second language in the time window during development from age four to eight when youths have an easier time acquiring language and other skills?

“Those college students may never produce or perceive sounds as a native speaker, but they can learn words and get much of the grammar right. They can communicate very fluently,” Zevin said.

Zevin’s arrival brings him full circle to his doctoral training. He earned his Ph.D. in neuroscience from USC Dornsife in 2003, under adviser Mark Seidenberg, now at University of Wisconsin-Madison. His doctoral research focused on computational models of reading, forging the path for his current work.

Previously, Zevin was an assistant professor of psychology in psychiatry at the Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology at Weill-Cornell Medical College in New York City.

At USC Dornsife, he is establishing a psycholinguistics and cognitive neuroscience laboratory. He said he looks forward to building a team of postdoctoral, graduate and undergraduate students to continue researching reading and speech perception. He is also looking forward to developing research partnerships with other faculty at USC.

“USC Dornsife has great strength in linguistics, psychology and neuroscience,” Zevin said. “It’s a perfect environment for interdisciplinary collaboration on studies.”

This semester, he is teaching an upper-level undergraduate course called “Psycholinguistics,” where students learn experimental and theoretical aspects of how spoken and written language is produced and understood. He also writes a blog called “The Magnet Is Always On,” where he discusses news and findings in his field.

Zevin said he is happy to be back at USC Dornsife, which has seen the addition of the Dana and David Dornsife Cognitive Neuroscience Imaging Center since he completed his doctoral degree. Now he can pop over to the neuroimaging facility to conduct his research.

“USC has just gotten better since I’ve left. It’s an amazing place to be.”