Methanol, a Fuel for the Future

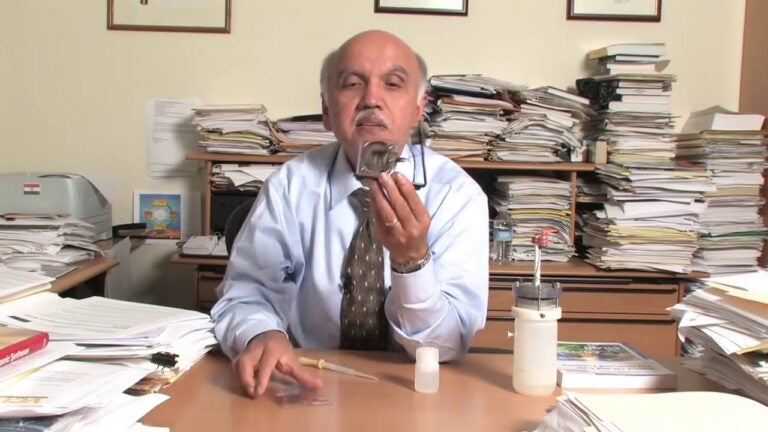

Surya Prakash, the George A. and Judith A. Olah Nobel Laureate Chair in Hydrocarbon Chemistry and Professor of Chemistry, demonstrates how methanol can be used as power. Video by Mira Zimet

Tapped by USC in 1977 during the world oil crisis to start a hydrocarbon institute from the ground floor, George Olah headed west, where he was more than up for the challenge. Olah, the Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, and Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Chair in Organic Chemistry, established the Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute that is housed in USC College.

Olah, who formerly taught at Case Western University in Cleveland, brought with him Surya Prakash, a brilliant young graduate student working in his laboratory, who completed his Ph.D. in chemistry from USC College in 1978. Prakash, the holder of the George A. and Judith A. Olah Nobel Laureate Chair in Hydrocarbon Chemistry and organic chemistry professor, has worked closely with Olah through the years as the institute has grown and experienced a multitude of scientific successes. And this includes a shared passion for the power and possibilities of the methanol economy.

“The energy conundrum is not about the energy, but its storage and energy carrier problems,” Prakash said.

Fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas that produce greenhouse warming carbon dioxide upon combustion, unlike methanol, are not only becoming depleted but are environmentally damaging. While nuclear plants don’t produce carbon dioxide, they are still problematic due to radioactive wastes and challenged by transmission and energy storage issues.

Sun and wind energy are excellent and clean sources of energy, but intermittent at best. Even in Southern California the sun does not shine much in June and the winds are not always blowing off the ocean.

Prakash said that most people are unaware that the energy dilemma comes down to the current 390 parts per million or 0.0390 percent of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. “By the end of the 19th century, carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere was 200 parts per million, but by the 21st century, it has grown to 390 parts per million and is expected to reach 550 parts per million by the end of this century, causing an imbalance and global warming and retention.”

Since 1989, Prakash has collaborated with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) administered by the California Institute of Technology to develop the methanol fuel cell as part of a project funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The agency sought a solution to charge the batteries of the communication equipment of military troops including the United States Army.

In the ’90s and in response to the DARPA request, Prakash, Olah and colleagues at JPL made a science altering discovery that has generated a huge intellectual property portfolio.

Explained in a fuel cell demonstration, Prakash shows how electricity is produced with a two-sided (anode and cathode) membrane electrode assembly that he brings with him as he gives talks around the world. The anode side of the apparatus is injected with two milliliters of 10 percent methanol and water mixture while the cathode side is exposed to air (oxygen). The chemical energy in methanol on reaction with oxygen in the air at the membrane electrode assembly turns into a very highly efficient DC electricity producing carbon dioxide and water.

“The gasoline engine in a car is roughly 17 percent efficient and requires a temperature of 600 to 700 degrees Celsius to operate — this is called well to wheel efficiency based on Carnot limitations,” Prakash said. “At room temperature, methanol can be up to 97 percent theoretically efficient.”

While multiple chemistry projects simultaneously percolate in his lab, Prakash along with Olah and colleagues at the institute continue to work on maximizing methanol efficiency and producing methanol from chemical recycling of carbon dioxide.

Prakash noted that Toshiba in Japan has produced two-watt/hour fuel cells for cell phones and laptops, and Smart Fuel Cells in Germany have manufactured similar devices using methanol for the U.S. Army.

“Methanol can also be used to produce diesel substitutes, petrochemicals, plastics, pharmaceuticals and agri-chemicals,” Prakash said. “China and Iceland are currently adapting some aspects of the methanol economy, and race cars are already fueled by methanol.”

Prakash foresees methanol powering laptops, cell phones, motorcycles, cars, trucks, locomotives, buses and ultimately homes. “Methanol is the fuel of the future. Its time has come,” Prakash said.

Olah, Prakash, and their research associate, Alain Goeppert, wrote 2006’s best-selling science book, now in its second edition and translated in five different languages, Beyond Oil and Gas: The Methanol Economy.

Prakash was appointed the director of the Loker Hydrocarbon Institute by Dean Howard Gillman in September, and Olah, the 1994 Nobel Prize Winner in Chemistry, who relinquished his position as the director, was named the institute’s Founding Director.

Related event:

On Monday, Oct. 18, the Annual George A. Olah Lecture in Chemistry will be held at 4 p.m. in room 123 of the Seeley G. Mudd Building featuring distinguished speaker Professor Helmut Schwarz of Technische Universität Berlin.