Kīlauea eruption fosters algae bloom in North Pacific Ocean

Volcanoes are often feared for their destructive power, but a new study reminds us that they can foster new growth.

A year ago in July, researchers from USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and the University of Hawaii rushed out on a boat to Hawaii’s famous KÄ«lauea volcano to collect samples of the surrounding North Pacific Ocean. They were trying to determine why so much algae had begun growing in the water as approximately 1 billion tonnes of hot lava poured in.

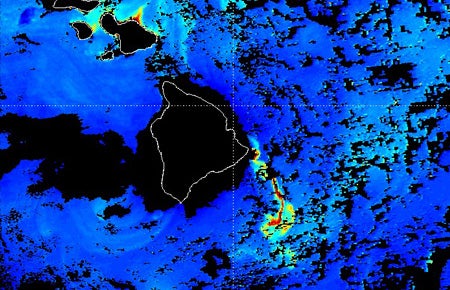

When looking at NASA’s satellite photos of the eruption, the scientists noticed that the ocean water around the volcano was turning green. The satellite had detected huge amounts of chlorophyll, the green pigment in algae and other plants that converts light into energy.

While investigating an algae super bloom near KÄ«lauea’s eruption last year, USC Dornsife researchers teamed with, from front to back, Eric Shimabukuro and Timothy Burrell, both of the University of Hawaii at Manoa, to gather ocean samples. (Photo: Nicholas Hawco.)

The new study, published Sept. 6 in the journal Science, shows that the green plume in the ocean around the volcano contained the perfect cocktail for plant growth — a fertile mix of higher nitrate levels, silicic acid, iron and phosphate.

“There was no reason for us to expect that an algae bloom like this would happen,” said geochemist Seth John, assistant professor of Earth sciences at USC Dornsife and an author of the study. “Lava doesn’t contain any nitrate.”

Nitrogen is a natural fertilizer for plants, even on land. With such rich conditions, the algae bloom exploded, expanding as far as hundreds of miles out into the Pacific Ocean, the researchers said.

“Usually, whenever an algae grows and divides, it gets eaten up right away by other plankton,” said study co-author and USC Dornsife post-doctoral researcher Nicholas Hawco. “The only way you get this bloom is if there is an imbalance.”

USC Dornsife researchers learned that the darkened boundaries surrounding KÄ«lauea on satellite images were a reflection of unusual algae growth, made possible by the unusual conditions of the volcano’s massive 2018 eruption. (Image: NASA.)

The researchers believe that the nitrogen likely was stirred up from the deep ocean. As the hot lava poured in, it forced an upwelling of colder, deep ocean water. When the water rose, it carried nitrogen and other particles to the surface that helped the algae grow.

“All along the coast of California, there is regular upwelling,” said John. “All the kelp beds and marine creatures that inhabit those ecosystems are basically driven by those currents that draw fertilizing nutrients up from deep water to the surface. That is essentially the same process that we saw in HawaiÊ»i, but faster.”

About the study

The study was supported by grants from the Simons Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Balzan Prize for Oceanography.