From Hollywood to Malibu: Mapping Joan Didion’s Los Angeles

For nearly five decades, Joan Didion has been one of California’s most compelling literary voices. Her coverage of zeitgeist moments, from ’60s “be-ins” to the election of Ronald Reagan, helped usher in an era of journalism where reporting read as engagingly as a novel. She’s penned books on Miami and El Salvador, covered national politics and now resides in New York City, yet California remains her work’s true north.

Although she was born and raised in Sacramento, Didion’s personal and spiritual nerves are particularly rooted in Los Angeles. In 1965, after an early career as a magazine writer and editor in New York, Didion and her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, moved to L.A.

They raised their daughter in Malibu, collaborated on Hollywood screenplays and socialized with celebrities, politicians and iconoclasts. From the 1960s into the ’80s, Didion piloted her car down smoggy boulevards in pursuit of the stories that showed L.A. to itself.

Using a new book he edited, Joan Didion: The 1960s & 70s (Library of America, November 2019), David Ulin, assistant professor of English at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, creates a map of Didion’s Los Angeles for those wishing to follow in her steps — or tire tracks.

7406 Franklin Avenue, Hollywood

In 1966, Didion and Dunne moved to a tattered, sprawling mansion at 7406 Franklin Avenue. There, as Hollywood pulsed around her, Didion wrote her collection of essays Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

Its skeptical observations of life in countercultural Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco echoed the vibrations of her own neighborhood, which was also undergoing a renaissance of a mixed caliber. Cultists, dreamers and criminals shared the same sidewalks, and downed martinis elbow to elbow at Musso and Frank Grill.

“It was a really marginal area, with a lot of transients in and out,” says Ulin. “There were big houses that had been mansions and were now spiritual cults and communes. There was a real temporary aspect to the neighborhood. This dovetails with her own internal sense of the tenuousness of the city and the era.”

In 1968, on assignment for Parade, photographer Julian Wasser snapped an iconic photo of Didion posing with her white Corvette Stingray in the Franklin house’s driveway. It was the beginning of her very deliberate, stylized presence on the cultural map.

“There are tons of well-done images of her taken across the span of her life,” Ulin says. “In every one of them you get the sense of her manufacturing image. In terms of the style of her prose, it’s a very self-conscious prose style; it’s aware of itself as style. So, it also makes sense that she would have that awareness of herself in the public eye.”

110: The Harbor Freeway

Freeways, the concrete arteries of the southland, appear frequently in Didion’s writing. To her, driving them requires a near ecstatic communion. “Actual participation requires a total surrender, a concentration so intense as to seem a kind of narcosis, a rapture-of-the-freeway,” she writes in her essay On the Road.

In the summer of 1965, the Watts Riots lit the city aflame. In her essay Los Angeles Notebook, Didion said of that August, “For days, one could drive the Harbor Freeway and see the city on fire, just as we had always known it would be in the end.”

Highways lend themselves to Didion’s detached, observational character.

“On the one hand there’s proximity as she’s close enough to see it, but she’s also separate because she’s above it all rather than on the streets of the neighborhood,” says Ulin. On an L.A. freeway, you can drive by a wreck, a fire or a riot and get within arm’s distance without ever leaving your air conditioning.

St. John’s Hospital

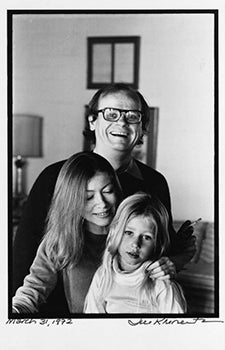

Didion pictured with Dunne and their daughter, Quintana Roo. (Photo: Courtesy of Jill Krementz; all rights reserved.)

By early June of 1968, both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy had been assassinated, the Vietnam war significantly escalated and protests were rising up across the globe.

That summer, Didion checked herself into St. John’s Hospital, now Providence St. John’s Health Center, in Santa Monica for “vertigo/nausea.” Later she reflects in The White Album (in which she also published excerpts from her hospital records during the stay), “By way of comment I offer only that an attack of vertigo and nausea does not now seem to me an inappropriate response to the summer of 1968.”

Didion’s petite frame, combined with the raw anxiety of her writing, gave her a reputation of frailness. She used it to her advantage, however.

“That smallness, that frailty, that physical slightness is something that she uses to get people to lower their guard so she can actually see what the real story is as a reporter,” says Ulin.

“Her writing is anything but frail,” he continues. “There’s a real toughness, even when she’s revealing information about her own psychological condition. That act of self-revelation is anything but slight. That’s a pretty powerful move to make.”

Happier events also occurred at the hospital. In 1966, a physician at St. John’s facilitated the private adoption of their daughter, Quintana Roo, named after a Mexican state on the Yucatán Peninsula.

714 Walden Drive

Didion’s brother-in-law, TV producer and consummate networker Dominick Dunne, and his wife, Lemmy, lived in a Hollywood Hills home not far from Didion’s Franklin Avenue digs.

Dominick Dunne was essential to connecting his brother and sister-in-law to lucrative Hollywood gigs after their move west, says Ulin. “The first movie that Didion and Dunne wrote together, Panic in Needle Park, he produced it. He was very instrumental in helping them get work and also in becoming part of that social milieu.” Didion often attended star-studded gatherings at the house, where she studied California’s elite up close.

It was also where Didion learned of the gruesome Manson murders, while swimming in the Dunne’s pool on an August evening in 1969. She later positioned the events as marking an end to buoyant ’60s naivety. Her 1979 book The White Album shares its name with the Beatles’ album that contains “Helter Skelter,” the song Manson claimed bore subliminal messages directing his violence.

Detour to Delano

If you’re looking for a Didion field trip outside L.A., head three hours north to Delano, in California’s Central Valley. In August 1966, she and her husband traveled to this small town to cover the grape workers’ strike organized by the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee.

Didion’s background in rural California was essential for Dunne’s fieldwork, says Ulin. “She had family history in Sacramento, which was very agricultural, and so she understood that territory in a way that Dunne, coming from the East Coast, did not.” The couple’s research later culminated in Dunne’s book Delano.

Didion and Dunne combined their talents on many projects together over their nearly 40 years of marriage. They produced screenplays, including A Star is Born and True Confessions, and wrote together for the The Saturday Evening Post.

33428 Pacific Coast Highway, Malibu

In 1971, Didion and her husband decamped to a rambling Malibu home floored with Spanish tile and decorated with a quilt sewn by Didion’s great-great-grandmother while on a westward wagon train in the 1800s.

Malibu was not all that different from their prior Hollywood neighborhood. It, too, was marginal, tacked onto the edge of the continent and hemmed in by a fire zone.

“They’re on a natural edge,” says Ulin. “I think that’s important in terms of her own sensibility and writing. For someone who is operating psychologically on that emotional fault line, she is putting herself geographically or physically into communities that are operating on their own fault line.”

Pummeled by the Pacific Ocean on one side and framed by tinder-dry hills on the other, Didion unraveled the Californian struggle with a nature both charming and cruel. In her essays, Malibu lifeguards pulled swimmers from the ocean, orchid growers tended their sensitive charges, and fires, spurred by Santa Ana winds, threatened humanity’s tenuous dominion over the land.

“Los Angeles weather is the weather of catastrophe, of apocalypse,” she writes in her 1965 essay The Santa Ana. “The violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The winds show us how close to the edge we are.”