How Charles Dickens created Christmas as we know it

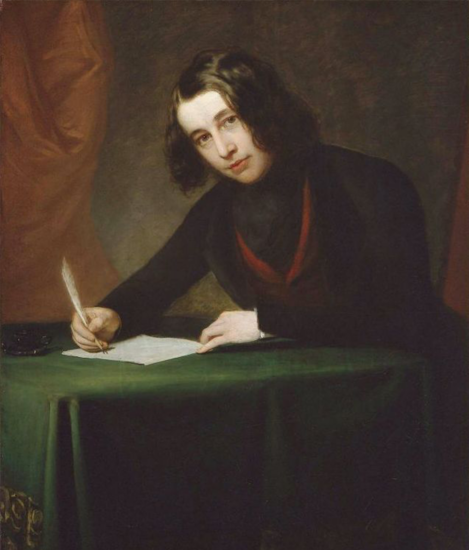

As the year comes to an end, many will enjoy a period of relaxation between Christmas and New Year’s Day. You may want to thank Victorian novelist Charles Dickens for the time off.

Dickens’ novella A Christmas Carol may be remembered today for its various film adaptions and the popular phrase “Bah! Humbug!”; however, the story’s influence is more far-reaching than most know.

Written during Britain’s Industrial Revolution, which was radically upending traditional ways of life, Dickens’ best-selling story was his persuasive plea for why we should keep the Christmas spirit alive.

“One of the things that Dickens was trying to do was to hang onto traditions. We don’t do Saint George’s Day or Saint Michael’s Day anymore, but he thought, ‘For God’s sakes, let’s hold on to Christmas,’” says Tok Thompson, professor (teaching) of anthropology. If you’re off work or school today for winter break, Dickens would consider his story a rousing success.

Charles Dickens classic stems from tumultuous times

When A Christmas Carol was published in 1843, Britain’s Industrial Revolution was in full swing.

Technological advancements had replaced handmade production of goods with factories. Many rural families moved into cities to find work. Once there, they often endured long workdays, dangerous labor conditions, and extreme poverty conditions.

“Farmer peasants were poor, but they had a lot of days off, food on the table and good community,” says Thompson. “Cities were not like that. You had debtor prisons, no worker protections, no child labor laws. It was vicious.”

Dickens experienced this firsthand. After his father was sent to a debtor prison, 12-year-old Dickens worked in a shoe-blacking factory. As an adult, visits to a “ragged school,” which housed street children, and a tour of Cornish mines that employed child laborers solidified his desire to alter social attitudes around poverty.

Dickens decided to write a persuasive Christmas tale, one that emphasized charity (especially towards children), benevolence toward workers, and holiday family gatherings. His story, featuring a miserly business owner, Ebenezer Scrooge, who has a change of heart over Christmas Eve, seems to have paid off.

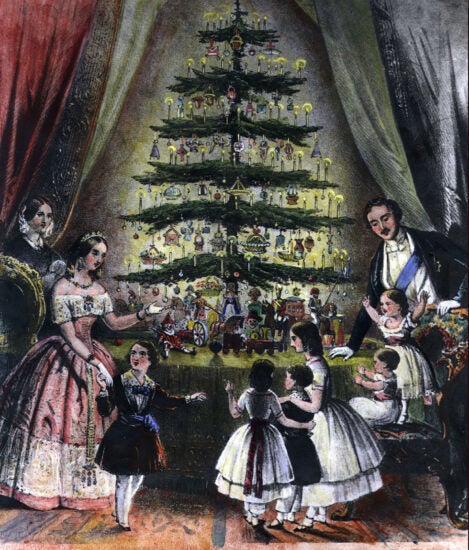

Christmas in Dickens’ era largely focused on fun and food, but today it’s equally associated with giving back. December is the most charitable month of the year. Those who are stingy towards others are called Scrooges.

A Christmas Carol wasn’t entirely driven by moral concerns. Dickens’ wife was pregnant with their fifth child at the time, and sales of his latest work had dropped off. The story was written in a mad rush in just six weeks. Thankfully for Dickens, it was an instant commercial success.

Why ghosts appear in A Christmas Carol

The exodus from the country prompted by the Industrial Revolution also threatened a loss of traditions and folklore. Those who left their ancestral villages might forget their histories. Extended winter breaks, ritualized in pastoral life, weren’t valued in modern factories. As the Industrial Revolution altered social customs, Dickens feared people would lose Christmas as a holiday altogether.

His tale was meant to demonstrate that Christmas could be an urban celebration, weaving old customs into the city environment. One of the oldest of these was ghosts, which appear as the specters of Christmas past, present and future.

Today, we mostly associate ghosts with the month of October. That’s thanks to an influx of Irish immigrants into the United States in the 1840s who brought with them the ancient autumnal celebration of Samhain. It was the Celtic New Year, a time when the veil between the worlds was thin and the dead could return for a time. This influenced the modern holiday of Halloween.

New years are often seen as “liminal periods” in folk traditions, says Thompson. “Liminal is a key word for a folklorist. It’s when things are undefined, neither this nor that, neither here nor there.”

Victorian England was influenced by ancient Germanic culture, which celebrates the new year during the “Yule” time in winter. It was a break for feasting and gathering with family, which conjured up the memories of dead ancestors — who perhaps would take advantage of the liminal space to make a visit themselves.

By placing old traditions in a new setting, Dickens proved that Christmas could be a city celebration. Indeed, snowy Victorian towns are commonplace holiday décor now. Dickens seems nearly synonymous with the season. A Christmas Carol even helped popularize the greeting “Merry Christmas.”

Scrooge: Christian allegory or therapeutic transformation?

Central to A Christmas Carol is Scrooge’s character transformation, from a miserly, isolated man to a magnanimous one. It nicely compliments Christian ideals of redemption, fitting for the holiday, but it’s not strictly a Christian allegory story.

“You can also read it as a kind of therapy session for Scrooge. He comes to realize what’s been holding him back, and how damaging that is,” says Kate Flint, Provost Professor of Art History and English. “It’s about realizing you can let yourself be happy, have an infectious laugh, find pleasure in giving, and also in other people’s sociability. Stop being scared of all this.”

Dickens seems to have believed that a self-reflective tale could change hearts and minds. It was a rather different approach to the problems of class than that of another writer of the era, who was also inspired by the Industrial Revolution. Karl Marx’s The Communist Manifesto was published just five years after A Christmas Carol.

“I think Dickens had a more optimistic view than Marx about whether capitalist bosses could change, and would not be completely greedy,” says Thompson.

Those eager to get into the Dickens spirit today should try reading the story aloud. It’s the way many would have first heard it. The book is divided into “staves,” just long enough for an evening’s read around the fire. In doing so, one can fully enjoy Dickens’ masterful writing, says Flint.

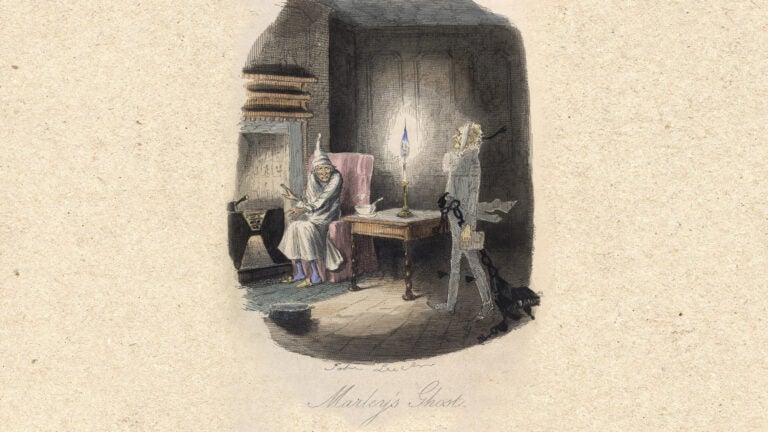

“Snippets of Dickens’s sense of humor come into view beautifully. For example, when Scrooge first sees Marley’s ghostly head on the door knocker, it’s luminous ‘like a bad lobster in a dark cellar,’” says Flint. “Dickens keeps one entertained at a really micro level, not just the bigger macro level of the plot. In a way, it shows that one can be generous and fun, and have that spirit of giving in language as well as anything else.”

If you’re looking for more spooky Christmas tales, Dickens actually wrote five novellas in the same vein. These include The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells that Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In and The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain.