Filmmaker and Rebel

In the communist-era Soviet bloc, all forms of artistic expression were subject to censorship and even suppression by the government. This reality gave rise to a dissident, grassroots practice called samizdat in which censored publications and films were covertly hand-reproduced and hand-distributed, from person to person, for underground consumption. It was an extremely risky undertaking, but often successful.

This is exactly how Polish film director Ryszard Bugajski’s 1982 feature film Interrogation, a carefully-researched depiction of Stalin-era political life that was banned by communist authorities, became one of Poland’s most popular films of the era.

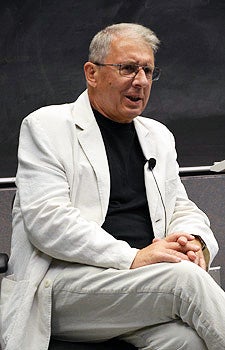

Warsaw-born Bugajski recounted his story Oct. 15 to students taking Assistant Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures Anna Krakus’ course “Crime Stories: Eastern European Fiction from Crime to Punishment.” His stop at Krakus’ class was part of a university-wide visit, including a screening of the film.

“In making this film, I wanted to look at the victims [of communism], the ordinary people, the people who were innocent and maybe not even interested in politics,” Bugajski told the students. “My heroine goes from a completely passive, politically unaware person to someone who starts to defend her own self and define her own moral code for the first time.”

The director described the unlikely origins of his controversial film, which he had developed for several years, and finally began shooting in the early 1980s during the rise of Solidarity in Poland, a short-lived movement of anti-bureaucracy and civil resistance.

Before he completed the film, however, martial law was imposed in Poland. Beginning in early 1982, this stringent period was intended to crush political opposition by severely restricting normal life — for example, people were no longer allowed to be out of their homes past dinnertime. This makes the film’s completion all the more impressive.

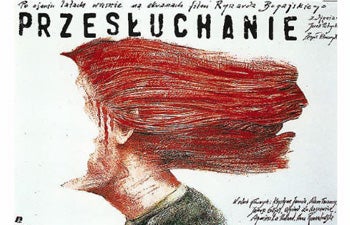

Designed by Andrzej Pagowski in 1989, this poster was created for Ryszard Bugajski’s 1982 film Interrogation (PrzesÅ‚uchanie in Polish). The film, a scathing criticism of the communist regime, was banned for 8 years in Poland, but later nominated for a Palme d’Or prize at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival.

Interrogation is a story concerning unjust imprisonment under the pro-Soviet regime of the early 1950s. The protagonist is a politically apathetic, fun-loving, young cabaret singer named Tonia, who is arrested without explanation and sent to political prison for interrogation. The prison officials use torture and humiliation to try to force her to confess to crimes she did not commit and implicate people she does not know.

When Interrogation was finally completed and reviewed at a censorship board hearing, it was denounced as anti-communist, banned and locked in a vault. Bugajski was forbidden from making any more films in Poland and eventually immigrated to Canada with his wife in 1985.

“I knew [the ban] would happen even while I was shooting it, so I surreptitiously made a copy of the film, a 35 mm print, and hid it,” Bugajski said. “Later I made more copies, dubbed it all into VHS, and it was distributed by an underground samizdat publisher. It became enormously successful.”

The quality of the VHS tapes was crude; people were often watching copies of copies of copies. Despite the terrible picture and sound, it was a profound act of resistance to see the film, usually screened in churches or private homes. According to Bugajski, the film uncovered the layers of lies and showed how communism really worked.

USC Dornsife sophomore Bradley Rava said Bugajski was a “wonder to listen to.”

“I was astounded by how dedicated he was to his film and creative ideas,” said Rava, an applied computational mathematics major. “He valued his movie and overall creativity over his own personal well-being. It really showed me how far someone would go to display their ideas and artistic talents even if, in his case, he was in opposition to the current regime.”

“In making this film, I wanted to look at the victims [of communism], the ordinary people, the people who were innocent and maybe not even interested in politics,” Ryszard Bugajski said during a recent visit to a USC Dornsife classroom. Photo by Erica Christianson.

During the event, a student asked how the director was able to create the prison and interrogation scenes with such accurate detail. Bugajski explained that some of this knowledge came from books such as Darkness at Noon and other nonfiction memoirs, documents and depositions from ex-prisoners that were smuggled in to Poland underground.

Another crucial source was an influential communist figure whom Bugajski met when he started writing the screenplay. She put him in contact with two women who had been in political prisons and these women became invaluable resources. Despite the danger, one woman served as a consultant to the set designer for the prison scenes.

After the fall of communism and the subsequent release of many banned films, Interrogation in 1990 was selected as the official Polish entry at the Cannes Film Festival. The film was nominated for a Palme d’Or prize and Krystyna Janda won best actress at the festival. The film has enduring significance for its deft characterization of the political situation under communism — it earned Bugajski a reputation as a specialist on communist secret police.

“I was so honored to have Mr. Bugajski in my classroom,” Krakus said. “Whenever I talk about him, I say that he is a filmmaker and a rebel — he made a film that no one else could possibly have made at a time when it was incredibly dangerous to make it. If that isn’t being a rebel, I don’t know what is.”

Krakus said Bugajski gave her students a firsthand account of a crucial time in history.

“I can teach the students to analyze and understand Bugajski’s film, but only he can teach them about the experience of creating it and help them understand the conditions under which it was made,” she said. “Hearing about how he was banned from making cinema for having presented an undesirable view, or about how his film was not publicly screened but instead kept in a locked vault — well, his stories bring my theory to life.”