Art’s Digital Revolution

Faded murals line the walls of the Palace of the Jaguars in Teotihuacan in the Valley of Mexico. But centuries ago, the jaguars glistened — illuminated only by natural sunlight — steeped in vibrant reds, blues, greens and oranges. At twilight on the summer solstice, shadows crept up the paintings, warping viewers’ perceptions of the colors.

And each year, on that summer night, it appeared as if the jaguars were leaping out of the surface of the wall.

Art historian Justin Underhill, USC Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Digital Humanities, recently published his paper “The Phenomenology of Sunset at the Palace of the Jaguars, Teotihuacan” in the journal World Art. His research describes the Purkinje effect, or the idea that — with decreased light — our eyes remain sensitive to greens and blues, while red hues become less visible, creating the effect of the jaguars’ momentary flight.

“Our society is unique in that we have essentially conquered the night,” Underhill said. “People 300 years ago were much more sensitive to fluctuations in daylight, and there are whole cities in the ancient world that are aligned to illuminate artwork at certain times of day.”

A mural at the Palace of the Jaguars. Photo courtesy of Justin Underhill.

Underhill’s work exemplifies the burgeoning field of digital humanities, in which scholars in disciplines such as history, literature and philosophy use technology to push the boundaries of their research. He compares his use of computer programming in art history to that of a scientist developing software to better understand the intricacies of chemical or biological reactions.

Underhill imagines how architecture and paintings once appeared based on unadulterated natural light and their alignments to the sun. Then, using computer software, he reconstructs buildings and archaeological sites — often ones that no longer exist or are in ruins — to show how light would have interacted with paintings at specific times in specific places.

Teotihuacan, for instance, flourished between 250 and 750 A.D. in present-day Mexico, and accounts of its culture have never been documented in writing. Our understanding of it comes only through archaeological investigations.

“I analyze how paintings of pyramids in Mexico came alive at twilight or how paintings kept in secret ceremonial dark places were activated by candles,” said Underhill, who earned a Ph.D. in art history from the University of California, Berkeley in 2012. “I do with architecture and artwork what actors on CSI [Crime Scene Investigation] do in crime scenes.”

Justin Underhill, a USC Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Digital Humanities, published a paper in World Art describing how natural lighting could change perceptions of color in ancient artworks. Photo by Amy Braden.

Where buildings were constructed also had a religious or even ritualistic significance in many cultures, Underhill said.

“Often looking at sites in a particular way reinforced a world view that allowed people to experience something divine,” Underhill said. “Many temples were built to reflect changes in the seasons or the way in which light filtered through a window to align with important events in the biblical calendar.”

This year the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation granted USC funding for four two-year postdoctoral fellowships in the digital humanities and 10 graduate student fellowships.

“Mellon is the major funder of the humanities in the world,” said Peter Mancall, vice dean for the humanities and professor of history and anthropology. “USC Dornsife was chosen because we have such a strong program in the humanities as well as stellar technological resources from the cinema school.”

Mancall, also Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities and Linda and Harlan Martens Director of the USC-Huntington Early Modern Studies Institute, believes that the grant will lead to discoveries that could never have been possible without employing modern technology.

“We are finding scholars at pivotal moments in their careers, either finishing dissertations or starting a postdocs, and giving them the most advanced tools to work on their projects and take them to levels that none of us can yet anticipate,” he said. “Justin’s research is breathtaking — cool beyond belief.”

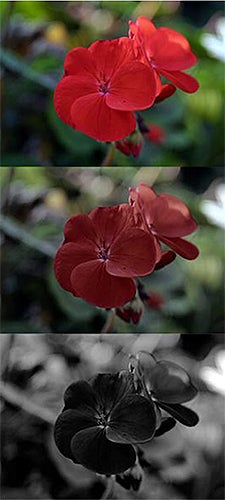

Illustration of the Purkinje effect, or the way in which our perception of the color red becomes less sensitive with decreased light. Photo courtesy of Justin Underhill.

Furthering his research at USC Dornsife, Underhill will incorporate the effects of how sounds people heard while viewing art — such as reverberating echoes or ethereal hymns — change the ways in which they interpreted the pieces.

“Sound is a whole other beast that requires different software,” he said. “Everyone at USC has been wonderful in helping me track down the right programs and learn how to use them.”

Underhill’s ultimate goal is to install his simulations in museums to heighten the experience for patrons.

“Clearly, it is not safe to give every museum visitor a candle and have them walk in front of a devotional icon,” he said. “But it is possible to mount a video next to a work of art and show how it would have looked. I think this melding of technology and art history will reinvigorate people’s ability to fully appreciate art in a way that was never before possible.”