Celestial Inspiration

Across much of Earth, pervasive light pollution now makes seeing most of them virtually impossible, but they are out there. Billions of them, pinpricks of light burning unfathomable distances from a blue and white marble orbiting a yellow dwarf star on the outskirts of a spiral galaxy known as the Milky Way.

Travel into the wild, away from populated areas, and we can see what our ancestors saw and share their sense of awe: countless jewels visible to the naked eye sparkling against the night sky, with the moon often dominating the view as it transitions through its phases from near invisible to a crescent shape to a luminous full disc and back again.

This view, and the possibilities it represents, have inspired some of humanity’s greatest artists to explore and express our sense of mystical wonder at the cosmos — and try to make sense of our place within it — through the arts and popular culture.

AN ENCHANTING VIEW

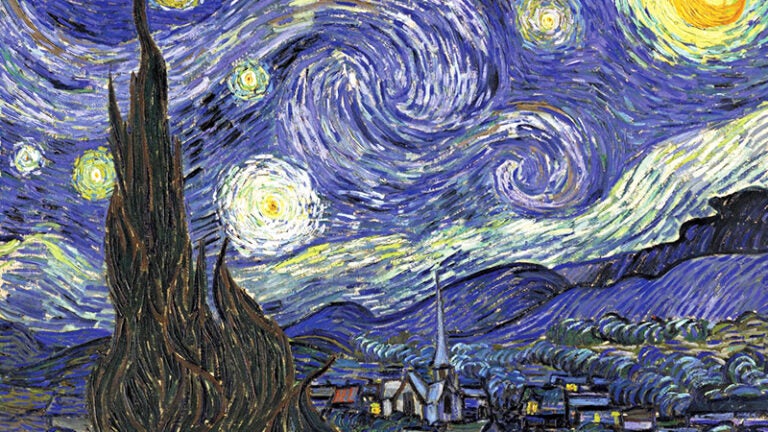

Gazing out of his asylum room window in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in southern France, Vincent van Gogh was struck by those sparkling lights in the night sky.

“This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big,” he wrote in a letter to his brother.

Whether he knew it or not, van Gogh was looking into space, seeing the planet Venus (the “morning star”) against a background of distant suns. This view of the night sky — and certainly his struggle with mental illness — led him to create one of the most famous portraits of the cosmos known to humankind.

“It’s this mysterious beauty and this really intense contemplation of the sky,” says Amy Ogata, professor of art history at USC Dornsife. “And that’s something probably that many people can identify with, of looking up and seeing these stars.”

Ogata’s assertion appears to be spot on, based on the popularity of the painting. The Starry Night, which van Gogh completed in 1889, is one of the most popular images in the world, captivating millions and appearing on everything from key chains to calendars to T-shirts and, of course, walls.

But it’s also something more. “What he has painted is not something that we would see if we were just going out to look up to the sky,” says Ogata. “He’s painted something that’s so super personal, this vision of this roiling sky that is flickering with this halo around this gibbous moon. … And then this kind of swirl that we could interpret as wind, as cloud, as reflected light, as emotion.”

It’s not a simple documentation of the artist’s view out of a window, she says. Much of it is made up.

Van Gogh doesn’t mention the moon in his note to his brother, only the morning star. And Ogata says the view from his asylum probably didn’t include a small village, or a church with a tall steeple, or a large cypress tree.

While inspired by his view of the night sky, the image is one of the artist’s making, his interpretation of what he sees in the heavens above him driven by his post-impressionist fascination with night and a near obsessive devotion to color.

And what more could we expect? It’s not as if he could travel into space for a closer look.

That would come later, as humanity’s ability to venture outside Earth’s atmosphere progressed over the next 70 years, in the process sparking the creative imaginations of writers, filmmakers, musicians and even fashion designers — all eager to imagine what the universe might hold.

A Trip to the Moon: Georges Méliès.

EARLY EXPLORATION

Science fiction as a distinct genre, and in particular the notion of traveling into space to visit other worlds, began to emerge during the Enlightenment. Scientific advances in physics and astronomy changed how humans viewed their world and its place in the universe. Earth was no longer at the center. Rather, it was one celestial body among many moving around a star and through the larger void of space.

For early science fiction writers, the moon — the closest extraterrestrial destination — was the obvious first stop when venturing into space.

German astronomer Johannes Kepler, a giant of scientific history responsible for foundational breakthroughs in our understanding of the motion of planets around the sun, penned what may be the first example in 1608. His novel, Somnium (Latin for The Dream), tells of a demon who can transport humans to the moon. The tale addresses various scientific concepts, including the transition from Earth’s gravity to the moon’s.

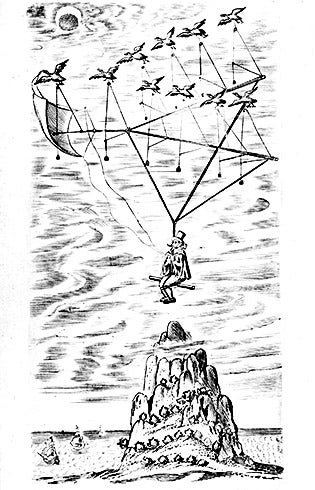

The Man in the Moone: Francis Godwin, Bishop of Hereford.

Two decades later, English historian and bishop Francis Godwin wrote The Man in the Moone, in which the protagonist builds a flying machine powered by swans that carries him to the lunar surface. This story, too, draws on the burgeoning astronomical theories of Kepler and other scientists.

Perhaps best known among early space-travel tales is French writer Jules Verne’s 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon: A Direct Route in 97 Hours, 20 Minutes, and its sequel, Around the Moon. The tales describe how the characters employ a massive canon to fire them at the moon in a large, hollow projectile.

Verne’s science fiction and adventure novels inspired several early motion pictures, including Georges Méliès’ 1902 masterpiece, A Trip to the Moon. The film, considered by many to be among the greatest ever made, pioneered deeply innovative special visual effects and produced one of the most iconic images in the history of cinema: a space capsule landing in the moon’s eye.

Space also inspired what is widely considered the worst movie ever made, Plan 9 from Outer Space. Shot in black and white in 1956, it features the final screen appearance by actor Bela Lugosi, though the footage of the faded celebrity had been shot for another movie and inserted into Plan 9, presumably to give it some star power. As for the plot, well, never mind.

THE GOLDEN AGE

Despite these remarkable early fictional endeavors, it wasn’t until the mid-20th century that stories of space adventure hit their stride. Inspired by earlier scientific advances — quantum theory, Einstein’s theory of relativity and the emergence of atomic energy — that all but guaranteed humans would soon find a way into outer space, writers such as Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Theodore Sturgeon and Frederick Pohl ushered in the Golden Age of science fiction. Joined later by the likes of Arthur C. Clarke, Poul Anderson and Philip K. Dick, these futurists and fantasists enthralled readers with their tales of deep space exploration, alien encounters, mysterious cosmic phenomena and alternate universes.

But for all their futuristic settings and devices, these stories bear roots in a seemingly simpler, and uniquely American, tradition, according to University Professor Leo Braudy, professor of English, art history and historyat USC Dornsife.

“I think it’s very much connected to the whole idea of the West,” he says. Like classic Western tales, stories of space travel embody the desire to escape to or explore an untamed, sometimes terrifying but also hopeful land, he explains, just as European settlers had been doing since shortly after they arrived on the shores of America’s East Coast.

“The idea of open space, the idea of somehow finding this place to build in, that you can restart civilization or, on the other hand, find monsters. There’s an interesting connection … in terms of popular culture between stories about the West and stories about outer space,” says Braudy, who holds the Leo S. Bing Chair in English and American Literature.

To affirm this connection to the American West, one need only look to one of pop culture’s most revered sci-fi phenomena, he notes. “That’s what Star Trek said: ‘Space, the final frontier,’ right?”

Pierre Cardin fashion photo courtesy of The Ebersole Hughes Company from their film House of Cardin.

SPACING OUT

By the 1960s, as humanity inched closer to the moon and experienced the breathless excitement of witnessing man’s first steps on its surface, the idea of a real future in space had infused the zeitgeist.

The Space Age changed the way designers looked at the world, influencing architecture, cars, furniture, appliances and fashion.

Paris fashion designers of the period, among them Pierre Cardin, Paco Rabanne and the so-called “godfather of Space-Age fashion,” André Courrèges, began to imagine a future among the stars. Who could forget those groovy flat ankle — or thigh-high — patent leather boots; chin-strap space bonnets; and minimalist silver mini dresses? Their influence has not abated, with leading designers such as Nicolas Ghesquière for Louis Vuitton and Raf Simons continuing the trend well into the new millennium.

According to Professor of Art History and History Vanessa Schwartz, author of Jet Age Aesthetic: The Glamour of Media in Motion (Yale University Press, 2020), the stage had already been set for the futuristic fantasies associated with the Space Age by the advent of jet travel.

“A Jet Age aesthetic developed in which the jet’s smooth and quiet ride extended to life on the ground in a variety of spaces and media experiences, such as newly redesigned airports, at Disneyland, and in the bright photos that circulated abundantly in news and fashion magazines,” says Schwartz, director of USC Dornsife’s Visual Studies Research Institute.

“People in the Jet Age lived as though the future had already arrived in the present, rather than dreaming of futuristic scenarios and styles.”

The cosmos also enthralled another group of artists: musicians. During World War I, British composer Gustav Holst wrote the innovative and influential orchestral suite, The Planets. Half a century later, popular music also found inspiration in the idea of space, particularly among those exploring the frontiers of their genre. Rock icon David Bowie, with his legendary “Space Oddity” and “Life on Mars,” jumped to the fore just as the Apollo missions finally put humans on the moon. And his iconic album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars would fully embrace the aesthetic with several space-influenced titles. Bowie displayed a lifelong fascination with the cosmos, with his final studio album — released two days before his death in 2016 — titled Blackstar.

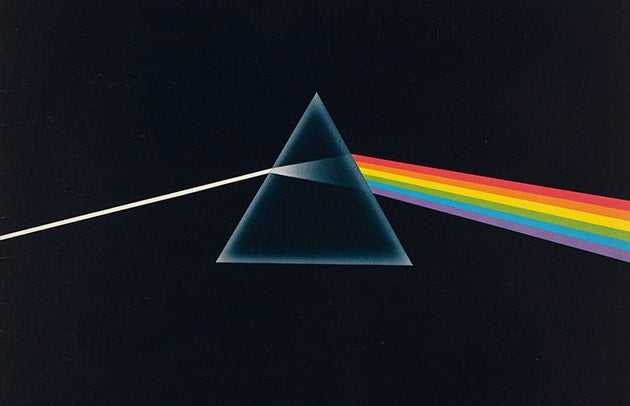

Other musicians — Elton John with his mournful ode to the “Rocket Man,” Pink Floyd exploring The Dark Side of the Moon and dozens more (too many to list) — shared Bowie’s fascination as space exploration proved an enduring inspiration.

The Dark Side of the Moon cover art by George Hardie ©The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

PUT IT ON SCREEN

As Hollywood began to translate science fiction stories to the big and small screens, visual appeal became an important component. Images of iridescent nebulae, stars streaked by “warp fields” and twin suns setting behind a planetary ring play to the eye, often with great success. But some viewers look for something deeper.

For Nicholas Warner, the most appealing fictional explorations of the cosmos focus on the characters, on how they address the unknown or unexpected, on how they problem-solve.

Professor of physics and astronomy and mathematics at USC Dornsife, Warner studies black holes. He grew up watching Doctor Who, the long-running (nearly 60 years!) BBC television sci-fi series depicting a “Time Lord” who travels through space and time. The show proved to be a key influence in his life.

“I knew I was going to be a scientist probably from the age of seven,” he says. “There was one thing that really reinforced it: Doctor Who.

“Here was a cool guy who went around figuring out how to solve problems, never used a weapon, and always outsmarted everybody.”

Warner, who occasionally serves as a science consultant in Hollywood, laments the sacrifice of thoughtfulness in favor of dazzling imagery. He cites 2014’s Interstellar as an example.

“So much of that movie and the essential plotting was driven by the visuals and not by any form of common sense.”

So, which movie gains the approval of a scientist like Warner?

“The Martian,” he says. “The fidelity of the science is great. You’re with the protagonist and he’s solving problems.”

In other words, it inspires us, not so much because it’s about space, but because of how we humans interact with it.

This ultimately rings true for all our cosmically inspired forays in creativity, be they Space-Age design, literary moonshots, great works of art, musical musings or visual flights of cinematic fancy. At their heart lies the human factor — our primal desire to push to the frontiers and beyond by challenging the limits of our Earth-bound existence through our imagination.