Why Dante and his ‘Divine Comedy’ remain relevant 700 years after his death

Dante’s Divine Comedy is the second-most translated book in the world. (Only the Bible has it beat.) It’s a staple on any list of the Western Canon and is standard reading fare for most college students in America.

But, why exactly, has a deeply religious medieval text about a journey to find God, peppered with graphic depictions of sinners writhing in hell, remained so culturally relevant? It’s partly, say scholars at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, because the text contains a universality that transcends Dante’s own era.

“It’s a poem that seeks to encompass everything, with artistic beauty and mathematical precision,” says Jay Rubenstein, professor of history. “The world, all the universe and everyone who ever lived is potentially a part of Dante’s story.”

It also offers up some of the most age-old of amusements — romance, gore and redemption — that are as captivating today as they were 700 years ago.

All the world’s his stage

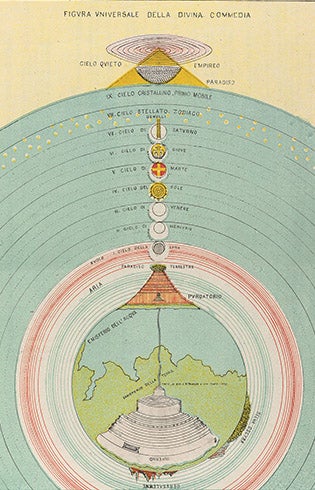

The Divine Comedy might be deeply religious — Dante himself wanted people to interpret it with the same rigor as people approached the Bible — but it endures in secular times partly for how thoroughly and imaginatively it organizes the cosmos. Dante takes the chaos and uncertainty of the afterlife and the universe and turns it all into a precisely structured map.

His studious organizing starts with the structure of the poem itself. The book is divided into 100 sections, or “cantos.” One canto serves as an introduction, and the remaining 99 are evenly divided among three books: Inferno (hell); Purgatorio (purgatory) and Paradiso (paradise).

Each of these realms is composed of nine rings, into which the dead are divvied up after their demise. The nine rings of heaven correspond with the planets and stars. “The world, the universe, humanity, the angels and demons — everything is in perfect balance,” says Rubenstein, who is director of USC Dornsife’s Center for the Premodern World.

Dante’s structure was so compelling that in 1588, a young Galileo Galilei attempted to map out the dimensions of hell as described by Dante. The exercise eventually convinced him that Dante’s fantasy could never be structurally achieved, taking an important first step, some say, toward theoretical physics.

Dante’s pilgrimage adds a third dimension: It is both an ascent, from the bowels of hell to the airy kingdom of heaven, and an inner journey, as Dante (and the reader) get closer and closer to meeting God. There are so many metaphysical layers to decipher that, 700 years after Dante’s death, scholars still have much to ponder.

May the punishment fit the crime

Of course, visionary genius only gets you so far. Dante’s work also persevered through the ages because of his penchant for captivatingly violent imagery. In his vision of hell, the condemned receive punishments that correspond with sins committed on Earth, a form of retribution dubbed “contrapasso.” The deranged forms of torture put to paper by Dante would fit seamlessly into any modern horror film.

Military leader Alexander the Great burns forever in a river of blood. Gluttons are forced to roll in stinking putrefaction, like swine in a pigpen, battered by freezing rain. Astrologers and false prophets have their heads twisted backwards as a comeuppance for leading others astray. At the very bottom of hell, the three worst sinners in history spend eternity having their skulls eaten by a three-headed Satan.

It seems both medieval and modern readers share an enduring penchant for the macabre. “We like shock and violence and gore as much as Dante did,” says Rubenstein.

Love lifts us up where we belong

Dante wasn’t just a horror fan, however. One of the reasons for Dante’s enduring popularity might also be his deep romanticism.

In the last book of the Divine Comedy, a woman named Beatrice takes Dante into paradise. (The Greek poet Virgil, Dante’s original guide, can’t enter the pearly gates because he’s a pagan.) Beatrice leads the reader both literally and figuratively into the realm of the divine, speaking eloquently about theology along the way. It is Beatrice who brings Dante face-to-face with God himself.

“In my opinion, Dante’s most significant contribution to medieval Christianity was reconciling romantic love with spiritual love. Whereas saints and martyrs abandoned the love of a woman for love of God, Dante showed how love could lead us to God and salvation,” says Kathryn Dickason, a recent postdoctoral scholar in religion and USC’s Society of Fellows in the Humanities.

Beatrice was more than just a fictional character. She was a real woman who lived in Florence, Dante’s place of birth, although her exact identity remains fuzzy.

For Dante, even her name is significant. The literal meaning of Beatrice is the blessed one, or one who confers blessing.

She was married to another man, and Dante only met her twice, but their brief encounters so affected him that he wrote a book of love poems for her, titled La Vita Nuova, and cast her as his guide to salvation in the Divine Comedy.

It’s all politics

The Divine Comedy might be primarily concerned with religion, but politics was also very much on Dante’s mind. At the time, Northern Italy was dominated by complex political divisions. For a while, Dante’s side was triumphant, and he began pursuing a career as a politician.

Unfortunately, his own party then split into opposing factions and Dante’s side was defeated. Dante was banished from Florence; his political aspirations were ruined and he would never again see the beloved city of his birth. Dante’s loss, however, was our gain.

“In terms of literature, it was a happy development. Dante would have been an obscure politician, probably, if his side had won. Instead, he had lots of time on his hands to develop his work of genius,” says Rubenstein.

His exile also inspired one of the most relatable journeys in literature. Dante began writing the Divine Comedy only after his expulsion from Florence, and it is as much an attempt to make sense of his estrangement from home (and his anger over the situation) as it is a spiritual journey to understand God.

“Dante is lost in a dark wood, which signifies the errancy of his soul. By the end of his epic journey, he gains both the desire to do good and the willpower to do good,” says Dickason. Dante concludes the Divine Comedy with these lines: “Here my high imagining failed out of power; but already my desire and the will were turned, like a wheel being moved evenly, by the Love that moves the sun and the other stars.”

“He clearly believed that salvation was possible even in the darkest of circumstances. I think people really resonate with this story of redemption.”

Dante would probably be pleased that his legacy is now so enduring that his home of Florence has spent centuries attempting to get his body back from Ravenna, Italy, where he died in 1321.

A tomb for Dante was built in Florence in 1829, but it remains empty.