In Memoriam: Andrei Simic

Andrei Simic, a beloved professor of anthropology at USC Dornsife who was described as a “scholar and gentleman from a world now past,” died on Dec. 26, 2017, in Phoenix. He was 87. The cause of death was Hodgkin lymphoma.

Simic’s primary area of specialization was the Balkans and Eastern Europe, but he had several secondary areas of interest, including Latin American Studies, ethnicity and nationalism, post-communist society, Euro-American ethnic groups, popular culture, social gerontology, and visual anthropology with a focus on film production and film analysis.

“Andrei Simic was an anthropological scholar whose work concerned the ethnography of Europe and the Balkans,” said Craig Stanford, professor of biological sciences and anthropology and co-director of the USC Jane Goodall Research Center. “But above all else, he was a truly beloved teacher who served USC students for decades, and a gentleman of the first order. His intellect, wit and kind nature will be missed by all who knew him.”

A sought-after authority

Simic often served as a consultant for a number of social groups, including the Armenian, Bulgarian, Portuguese, Romanian, and Spanish communities, as well as various East European and Latino associations. Through the years, he was also called upon to consult or provide testimony in a wide range of legal matters, some of which were highly controversial. These included several cases involving Roma defendants; the Amicus Curiae Briefs relating to the controversial Kennewick Man Dispute in 2003 and the Spirit Cave Artifacts in 2005; and most recently, in 2016, an affidavit in defense of a homosexual Serbian national seeking asylum in the United States whose case, according to the attorney involved, was ultimately won because of Simic’s statement.

Simic was the author of several books, including The Peasant Urbanites: A Study of Rural-Urban Mobility in Serbia (Seminar Press, 1973), considered by many in the field to be a seminal work on post-World War II migration patterns in former Yugoslavia. He was a prolific researcher and writer who published numerous articles in academic journals as well as in a wide variety of other publications. He presented research papers at various academic meetings and as an invited lecturer, and conducted ongoing research projects on various aspects of Balkan culture.

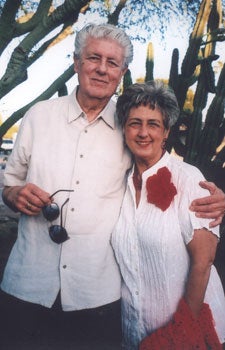

Andrei Simic, left, and his wife, Maria Budisavljevic Oparnica Simic.

In addition to his written work, Simic was credited and involved in the production of 27 ethnographic films, including his two major film projects, 1987’s “Ziveli: Medicine for the Heart” and 2004’s “The Children of Lazo’s Grove” in collaboration with his wife, Maria Budisavljevic Oparnica Simic.

He also presented several major photo exhibits, all focusing on Yugoslav ethnographic issues. The most recent in 2004, “Five Decades of Serbian Life in America: Family and Archival Photographs —1893-1947,” a collaboration with his wife, was presented in Belgrade.

Simic was a member of various academic associations, including the North American Association for Serbian Studies and the Union of Serbian Writers, to which he was elected in 1991.

Worlds of wonder

Simic was born Aug. 21, 1930, in San Francisco. His father, Novak Simic, was a Yugoslav diplomat, and his mother, Marjorie Williams Simic, was an elementary school teacher.

From earliest childhood, Andrei Simic’s imagination was engaged in creative and artistic endeavors. When he was five, he began to write about and draw pictures of his imaginary “homeland,” a planet that he called “Andreinia.” He developed and defined the regions of that planet throughout his life by drawing not only pictures of the land and its inhabitants, but also geographical and topographical maps of it, and by establishing a social hierarchy. He continued this development until just days before his death.

Simic embraced another world of wonder beginning in his childhood when he became aware of and keenly interested in his own Serbian heritage and in all things Slavic. He attributed this interest to the influence of his father, a Serb who had been a medical student in Russia when the revolution erupted, and who subsequently served as a physician with the White Army. Simic’s father regaled his son with romantic stories about his adventures in Russia and the Balkans, including a fairy tale about having grown up in a castle in Herzegovina.

A meticulous researcher, Simic could always be trusted to translate into clear and fluid language the often complicated ideas about culture and tradition held by various Balkan and other peoples. This writing style was consistent no matter the topic of the text, an indication of his innate sincerity and goodwill.

This same sense of accessibility was evident in his human relationships, as well. Many friends, colleagues, and especially students commented about his lack of pretentiousness and his extraordinary ability to put people at ease.

“Andrei was one of a kind, an old soul, a scholar and gentleman from a world now past, but hardly passé,” said Jennifer Cool, assistant professor (teaching) of anthropology. “Beloved by generations — many of his students continued to visit him in office hours decades after graduation — Andrei always had time for a good conversation, whether in Spanish, French, Russian, Serbo-Croatian, or English.”

Renaissance man

Simic held a diversity of interests, abilities and pursuits. In addition to many other talents, Simic was an artist. He had attended art classes as a young man in Berkeley, Calif., and was skilled in various media, preferring to work in oils but not limiting himself to any one genre. He was often heard to say that he never felt he quite belonged “in this world,” and referring to an old Yugoslav film, “Nesto izmedju” (“Something In-Between”), determined that he, too, was “something in-between.” That quality of belonging nowhere and belonging everywhere may have enabled Simic to discover and share so many homelands here on this planet.

Simic is survived by his wife, Maria Budisavljevic Oparnica Simic, whom he married in 1997; daughters Denee Ana Simic and Alisha Saveta Dagis (Andrew); step-son, James A. Struckmeyer III; niece Nova Wallace Alfert; nephews Andrei Wallace, Anthony Wallace and Gerald Wallace and their families; and several relatives in former Yugoslavia.