Experts discuss the Nazi’s use of propaganda to advance their cause

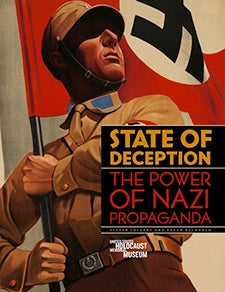

A painting of a handsome square-jawed man wearing an army uniform looks ahead into the future, a flag waving behind him. It’s an image that evokes strong emotions — exactly as it was meant to do.

The flag, emblazoned with a swastika, was designed by the Nazis to rally support for their cause among the German people.

The image and others like it were the topic of a “Casden Conversation” at USC on March 6. Sponsored by the Casden Institute for the Study of the Jewish Role in American Life, the event featured a discussion between Stephen Smith, executive director of USC Shoah Foundation — the Institute for Visual History and Education, and Steven Luckert, curator of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s special exhibit “State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda.”

The exhibit is currently on display at the Los Angeles Public Library’s central branch in downtown L.A.

What is propaganda?

Overseen by Joseph Goebbels, propaganda was an integral part of Hitler’s rise to power. It then became a way to make the Holocaust seem more palatable to the German people.

As one survivor explained in a short film shown at the start of the presentation: “The Holocaust did not start with murder. The Holocaust started with propaganda.”

The book cover of State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda, written by Steven Luckert and Susan Bachrach. The image is from a poster for the 1933 film S.A. Mann Brand. Kunstbibliothek Berlin/BPK, Berlin/Art Resource, NY.

Smith, who holds the Andrew J. and Erna Finci Viterbi Executive Director Chair of the USC Shoah Foundation, launched the conversation by asking what is propaganda.

“When I hear the word ‘propaganda,’ I automatically assume it has a negative connotation,” Smith said. “Is the word getting a bad rap when it’s always associated with negative, totalitarian regimes and hateful organizations?”

Luckert explained that the term originally had to do with the propagation of plants and animals, but then later changed to mean the spreading of religious doctrine. It wasn’t until World War I that it became associated with negative manipulation.

“We wanted people to think about what propaganda is and how it functions,” he said. “We define propaganda as the biased information designed to shape public opinion and behavior. It can be true, partially true or blatantly false, and plays on emotions.”

But propaganda doesn’t work in a vacuum. The deception requires someone to accept it as true.

“Not only is it the conscious effort on the part of the Nazi party to manipulate audiences,” Luckert said. “The audience can deceive itself by buying into the deception. If an audience doesn’t buy into it, it doesn’t work.”

Hitler’s obsession with imagery

In the years leading up to Hitler’s rise to power, the Nazis needed to win public support, so they used propaganda to convey a sense of strength and unity. Whether through artwork, films or the fairly new medium of radio, the Nazis were masters of stoking emotions. Luckert said they even used television, then in its infancy, to further its ends.

One early image Luckert showed contained only a close-up of Hitler’s frowning face staring directly back at the viewer. In a particularly unnerving painting, Hitler stands in front of a group of people while light seems to shine from his face into the crowd. Using a less-than-subtle religious reference, he titled the painting, “In the Beginning Was the Word.” This painting was considered so potent that the U.S. Army never returned it to Germany after the war.

Nazis as niche marketers

Notably, overt anti-Semitism was largely missing from early Nazi propaganda. Their focus was gaining influence, not the Final Solution. But that changed as Hitler consolidated his power. Cartoons of shifty-looking caricatures of men with large noses began to appear. Others warned Germans not to trust the Jews, who cared only about money.

Masters of niche marketing, Nazis targeted specific groups of people with their propaganda.

“This is a party that has no record of supporting women’s rights, has no women in its parliamentary delegation, yet it’s successful in winning over a large number of women,” he said. “It astounded people.”

The propaganda campaign was so successful that the Nazis were able to convince an entire nation to follow their path to destruction.

“Even for people who saw in Nazi ideology something they found offensive, whether anti-Semitism or militarization, they would overlook that in favor of something very vague,” he said. “The Nazis used amorphous but very appealing slogans — ‘work,’ ‘bread,’ ‘freedom.’ Those are appealing to everybody.”