In Memoriam: Sidney W. Benson, 93

USC Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Chemistry Sidney W. Benson, who became scientific co-director of USC Dornsife’s Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute when it opened in 1977, has died. He was 93.

Among the world’s most-cited chemists, Benson published more than 500 scientific papers and books on physical chemistry. His research in thermochemistry transformed a once esoteric field into an active branch of modern chemistry. Those who work at modeling complex chemical processes such as air pollution, the ozone layer, combustion, or explosions make use of Benson’s fundamental contributions.

Benson died Friday, Dec. 30, at his home in Brentwood, Calif., after complications from a stroke, his wife of 26 years Anna Bruni Benson said.

In 1977, Benson helped to recruit George Olah, now Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, and Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Chair in Organic Chemistry.

As winners of the American Chemical Society Award in Petroleum Chemistry, Olah in 1977 established the Hydrocarbon Research Institute and Benson became scientific co-director. Later named after the Lokers, it is the nation’s only university-based institution devoted to hydrocarbon research and training, and the only privately funded research center of its kind.

Olah’s research at the institute earned him a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1994.

“In the fall of 1976, I got a phone call from an old friend and his name was Sid Benson,” Olah recalled. “He asked me if I was interested in coming to USC. He was the first person who contacted me. He was a friend and a great scholar.”

The institute’s director G.K. Surya Prakash, George A. and Judith A. Olah Nobel Laureate Chair in Hydrocarbon Chemistry, and professor of chemistry, first met Benson when Prakash was a Ph.D. student at USC.

“Sid was one of the most optimistic scientists I’ve ever met,” Prakash said. “He believed in the future. He was also a great human being. He was always very kind with his younger colleagues.”

Prakash said that unlike many scientists, Benson wasn’t preoccupied with funding, but always focused on the research.

“His philosophy was ‘do good work and good things will happen,’ ” Prakash said.

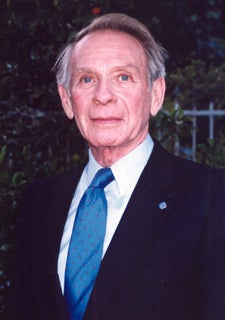

Chemist Sidney W. Benson in 1986 was awarded the USC Presidential Medallion, the university’s top recognition for those who have brought honor and distinction to the campus. Photo by Anna Bruni Benson.

And they did. In 2008, when Los Angeles Lakers owner Jerry Buss pledged $7.5 million to USC Dornsife, it was in part to establish an endowed chair in honor of his mentor, friend and former USC chemistry professor Sidney Benson.

“As an academician and a person, Sidney Benson was inspiring,” said Buss, who earned his Ph.D. in chemistry from USC Dornsife in 1957. “He was a role model, and to a young student, a little intimidating.”

Chi Mak, professor and chair of chemistry in USC Dornsife, said Benson will be remembered for his profound originality and creativity and as a world-renowned expert in the energetics and kinetics of chemical reactions. He said Benson’s studies of reactions involving free radicals are of key importance to our present understanding of atmospheric chemistry and combustion.

“Sid was a walking encyclopedia on bond dissociation energies, and his ability to precisely predict the energy of any chemical bond in any compound was simply magical,” Mak said.

One of Benson’s greatest accomplishments was his idea of using group additivity to calculate the thermochemical properties of complex molecules and bond dissociation energies, Mak said.

“More than 50 years later, the accuracy of these predictions still rivals those generated by the fastest supercomputers based on the most advanced computational chemistry algorithms today,” Mak said.

Benson joined USC Dornsife in 1943, becoming the sixth faculty member in the Department of Chemistry.

When he arrived, there were 6,000 students and 350 full-time faculty members university-wide. That’s compared to 37,000 students and 3,300 full-time faculty now.

“There was no machine shop or glass shop in the chemistry department,” Benson reflected in a 1990 YouTube interview, part of the USC Emeriti Center’s H. Dale Hilton Living History Project. “Remember, this was the end of 1943. We are nearing the end of a war and USC is not yet a research university. USC started as a collection of professional schools. It had aspirations and hopes of becoming a research university and I think that’s why I was hired.”

After the war ended, “the campus doubled in size,” Benson recalled. “There were so many students USC had to borrow 20 barracks from the U.S. Department of Defense. So our labs and classrooms were in barracks. Some of my best work was done in those barracks. I can’t knock the barracks.”

USC Dornsife’s Sidney W. Benson’s research in thermochemistry transformed a once esoteric field into an active branch of modern chemistry. Here, he sits in his laboratory in 1982. Photo by Wendy Rosin Malecki courtesy of USC University Archives.

Born Sept. 26, 1918 in New York City, Benson was among the few hundred exceptional students selected to attend what is now The Bronx High School of Science. In 1938, he earned his A.B. degree with honors in chemistry, physics and mathematics from Columbia College. He obtained his Ph.D. in physical chemistry in 1941 from Harvard University, studying under George Kistiakowsky, a chemistry professor who participated in the Manhattan Project and later served as President Eisenhower’s science adviser.

After a stint teaching at the City College of New York, Benson served as a group leader at Kellex Corporation for the Manhattan Project, the research program that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II.

From 1943 to 1963, he rose through the ranks at USC Dornsife. In addition to his research contributions, in 1947 he co-founded USC’s first governance body, the University Senate, serving as its initial secretary while well-known English professor Frank Baxter became its first president. The group created many changes at USC after the post-World War II G.I. Bill of Rights led to massive increases in the student population.

During his 1990 interview, Benson recalled a tumultuous time when his group negotiated a pay raise for full-time faculty with then-USC President Rufus B. von KleinSmid. At the time, salary for full-time professors ranged from $1,900 to $4,000 a year, he said. After much effort, the fledgling senate secured an initial 10 percent raise.

In 1963, Benson took a post at the Stanford Research Institute, where his colleagues say they were privileged to work with him.

David Golden, professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University, said he also got to know all of Benson’s junior colleagues.

“It is striking that there always existed among us a unanimous affection that went far beyond scientific collaboration,” Benson said.

An expert in air pollution formation as a combustion process, Benson said he took the position in northern California because his wife became allergic to the Los Angeles smog. But in 1976, they returned to L.A., and Benson to USC.

In 1981, Benson became the second scholar at USC elected to the National Academy of Sciences. Now, USC has 16 National Academy of Sciences members.

When asked in 1990 what makes him the most proud of all his work at USC, he answered:

“I’m proud that my election to the National Academy of Sciences was given to me on the basis of my work at USC,” Benson said. “The other thing I’m proud of is my work in the past 10 years at the Loker Institute in the development of patents — two of which look like they will bring back appreciable sums of money to the university.”

Benson was dearly loved by his undergraduates, graduates and post-doctoral researchers.

“He did more for me than even my father did,” said Benson’s former Ph.D. student R. “Sri” Srinivasan, who went on to co-invent LASIK, a procedure to correct vision, and is listed in the National Inventors Hall of Fame. “Therefore, there is a void in my heart.”

Benson’s textbook The Foundations of Chemical Kinetics, first published by Krieger Publishing Co. in 1960, remains a seminal contribution to the field. Another major book includes Thermochemical Kinetics: Methods for the Estimation of Thermochemical Data and Rate Parameters (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2nd ed., 1976).

He earned many honors, including a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1984, he received the USC Associates Award for Creativity in Research and Scholarship. In 1986, he was awarded the USC Presidential Medallion, the university’s top recognition for those who have brought honor and distinction to the campus. He received the USC Faculty Lifetime Achievement Award in 1990 and retired in 1994.

In addition to his wife Anna Bruni Benson, he is survived by his son Nicholas; his adopted daughter Jeannette Hamilton; stepchildren Mara Lee Maltauro, Sumishta Brahm and Mark Seldis; granddaughter Sydney; brother Albert; and sister Rhoda.

USC Dornsife’s Department of Chemistry is organizing a memorial to take place this month. For more information, contact Prakash at gprakash@usc.edu or Mak at cmak@usc.edu.