Grotesque yet beloved: the fascination with Abraham Lincoln’s body

Speaking to an 1856 convention of newspaper editors in Decatur, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, never at a loss for a humorous quip or story, told this amusing tale.

While riding a horse through the woods, a man Lincoln described as “not possessed of features the ladies would call handsome,” stopped on the path to let a woman rider pass.

She stopped in turn and said, “Well, for land sake, you are the homeliest man I ever saw.”

“Yes, madam, but I cannot help it.”

“No I suppose not,” she said, “but you might stay at home.”

Richard Fox, professor of history at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, recounts this anecdote in his new book Lincoln’s Body: A Cultural History (W.W. Norton & Company, 2015). The tale, reported decades later by one of those present, was thought to be a “personal reminiscence” on the part of Lincoln.

Examining images, speeches, monuments, Hollywood movies, and many other sources, Fox charts the ways Americans have remembered and imagined Lincoln and used his physical presence as a vehicle for evaluating Lincoln’s continuing impact on American culture.

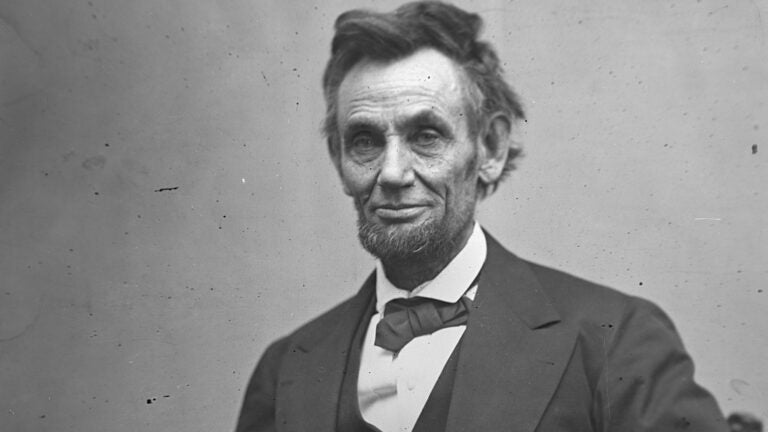

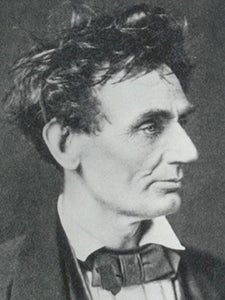

“During Lincoln’s lifetime, everybody was preoccupied with his looks and that meant his physical appearance, as well as the way he dressed, the way he carried his body,” Fox said. “When people used the word grotesque to describe him — and that was an adjective used by friends as well as foes — they meant not hideous, but uncanny or alien.”

In his book, Fox explores how Lincoln used his innate gift for humor and storytelling to make light of what everyone concurred was his unfortunate physical frame. He was thereby able to overcome what might have been a serious handicap, even turning his gift for comical self-depreciation to his advantage as a political tool. “Millions were inspired by Lincoln’s knowing how to overcome the unfortunate hand nature had dealt him,” Fox writes.

“He himself thought he’d been dealt a poor hand in personal looks, but it never stopped him,” Fox said. “I think that’s why millions of people found him so endearing, because he would make fun of his own appearance. Some of his most humorous remarks are about it and that, of course, made him irresistible.”

As a result, despite the jokes and the insults — or perhaps because of them — Lincoln’s body, all six foot, four inches of it, occupied a unique place in the hearts and minds of Americans for generations.

However, by the 1970s, this obsession with Lincoln’s appearance — and the use to which he had put his body — was fading, to be replaced in the 1990s with a fixation on his words. Fox credits Daniel Day Lewis’s performance in Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film Lincoln with reviving interest in Lincoln’s looks, accessibility and physical sacrifice —and in confirming his role as an emancipator.

“Most people pay little conscious attention to Lincoln’s body these days, but once they focus on it they can see how it’s been tied to his words and deeds ever since he entered politics,” Fox writes. Lincoln’s physical being fascinated his contemporaries, as well as following generations, he argues, because they realized how much it mattered to him.

“Lincoln made people care about [his body] by tying it to their national saga,” Fox writes in his book. “Only in America was self-making possible on such a grand scale, he kept saying, and only in America, was a man like him — of such unprepossessing origins, in appearance and social standing — able to rise to such heights of power and respect.”

After commencing his book with an examination of the importance of Lincoln’s looks, Fox moves on to what he calls “the second dimension” — the accessibility of Lincoln’s body, in life and in death.

“He had learned early on from Illinois politics in the 1830s and ’40s that if he could get people into the same room with him, they stopped seeing ugliness in his face because they reveled in his animation,” Fox said, noting the transformation of Lincoln’s appearance when he engaged in conversation, or delivered speeches.

Yet, his desire to mingle with the people — to show them they were living not in a monarchy, but in a republic, where leaders ultimately go back to being average citizens once their terms of office end, Fox argues, increased his chances of being attacked.

Thus the historian believes that a now almost forgotten event that occurred 10 days before his assassination can help advance our understanding of Lincoln. It shows that for him republicanism was a way of living, not just a doctrine.

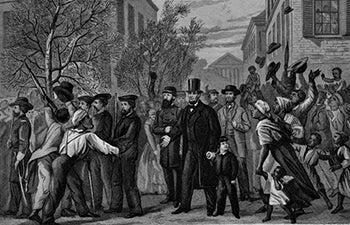

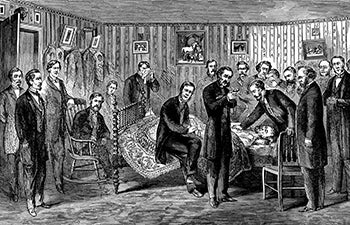

The Civil War was almost over in Virginia when Confederate troops withdrew from Richmond during the night of April 2-3, 1865. On April 4, Lincoln arrived in the city and walked through the streets surrounded by thousands of slaves who were, in practice, now free to welcome their emancipator.

“I don’t think we can begin to imagine how that felt to the slaves of Virginia,” Fox said. “Their liberator had arrived in their midst. And Lincoln made that happen himself. He could have waited at the dock for an army vehicle. But instead, protected only by the mariners who had rowed him ashore, he walked out into the streets, hand-in-hand with his 12 year-old son, Tad, with the crowd growing bigger minute by minute. The spring afternoon was hot and smoky, because the ruins of Richmond were still smoldering, but he trekked through the downtown all the way up to the former Confederate White House, which was now Union army headquarters.”

This moment, Fox maintains, underscores Lincoln’s accessibility and what some later perceived as his vulnerability.

“I never expected that a Republican friend of Lincoln would blame him for his own assassination, but that’s what happened,” Fox said. “Henry Raymond, the editor of The New York Times, wrote in the paper on the day that Lincoln’s corpse arrived in Manhattan that Lincoln was ‘culpably remiss’ in making himself so accessible that he could be shot. In fact, Raymond said he was ‘far more surprised that [Lincoln] was not assassinated months or years ago, than that he did at last perish by the hand’ of John Wilkes Booth.”

Fox estimates that six million people saw the funeral train carrying Lincoln’s body from Washington, D.C., to its final resting place in Springfield, Illinois, and another million people probably saw his face in death during the 12 different lyings-in-state in six states, plus the District of Columbia.

By the end of the journey, anxious officials brought the funeral forward by two days, so worried were they by the rapid decomposition of Lincoln’s corpse.

Fox believes the accessibility of Lincoln’s body in death echoed how he wanted himself to be accessible to all people during his lifetime.

“In my book, I tried to present black experiences of Lincoln as being equal to white experiences,” he said. “I felt that was my responsibility since Lincoln was so clear about his commitment to natural equality and to greater civic equality.”