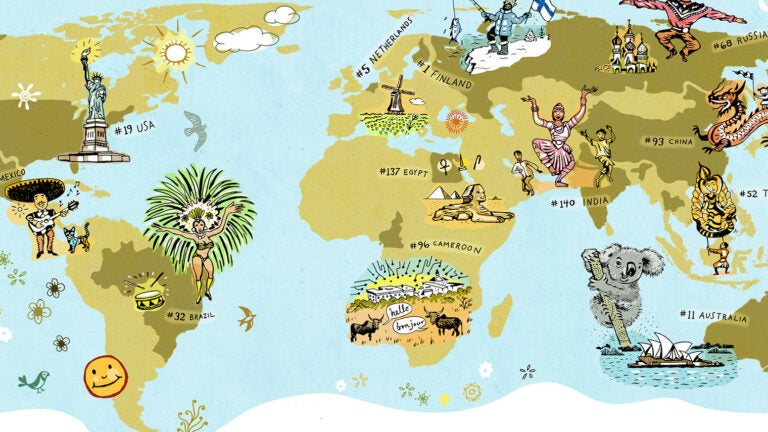

Happiness Around the Globe

Finland, a land of the midnight sun up at the top of the world, is known for its intriguing history, excellent education system, flourishing culinary scene and natural wonders such as the aurora borealis. The Nordic country may be cold and remote, but it is also literally the happiest place on Earth. (Sorry, Disneyland.)

The latest World Happiness Report indicates that, among citizens of the 156 countries around the globe queried by Gallup for the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Finns were the most satisfied with their income, freedom, trust in their government, health, generosity and social support. Most of Northern Europe was right behind them: Denmark, Norway, Iceland and the Netherlands, respectively, rounded out the top-five happiest countries.

These countries tend to be wealthier, though that factor alone is not what propels them to the top of the list, explains Arie Kapteyn. An economist who directs the Center for Economic and Social Research at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Kapteyn studies how economic decision-making affects health and well-being.

Research findings suggest that rich countries provide things that improve the quality of life, he said. “The people in these countries are healthier. They’re safer. More educated.”

He also notes that their governments are less corrupt and people feel a sense of fairness in how incomes are distributed. In Europe, there are also more social safety nets in place, from universal health care to pensions for the elderly, which play a significant role in life satisfaction.

“Evidence shows that these all make a difference,” he said.

Happiness, Ranked

Why measure happiness, and how exactly do we quantify something so subjective?

Think about it like this, says Kapteyn: If we understand what makes people happy — stable governments, good health, a secure income, a sense of community — we can structure policies that strive for those outcomes.

“Happiness is really the most reasonable goal for policy,” he said.

So how do we put a number on something so nebulous? Arthur Stone explains. He directs the Center for Self-Report Science at USC Dornsife and is an expert on subjective well-being — the scientific term for happiness and life satisfaction.

The World Happiness Report uses an evaluation called the “Cantril Ladder.” The method asks respondents to think of a numbered ladder, with the best possible life for them being a 10 at the top, and the worst possible life being a zero at the bottom. They then use the ladder to rate the current status of their lives in six different areas: gross domestic product per capita, life expectancy, generosity, social support, freedom and trust in their government.

However, Stone warns that measuring happiness across cultures is not a straightforward endeavor. How people perceive what constitutes happiness, and the language that people use to describe their well-being, vary from culture to culture.

“Happiness may not translate in exactly the same way across countries,” he said.

A growing body of evidence in recent decades has revealed just how emotions can differ from country to country. Authors of a September 2004 study published by the Journal of Happiness Studies examined this very point.

Americans value autonomy, so performing well on a test, or making the game-winning touchdown, for example, are considered happy moments.

In North America, “happiness may most typically be construed as a state contingent on both personal achievement and positivity of the personal self,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, in East Asia, happiness is likely to be construed as a state that is contingent on social harmony.”

United States of Unhappy?

Despite its prosperity, the United States ranked No. 19, down one spot from 2018 and five spots down from 2017. What gives?

The report postulates that various forms of addiction — from substance abuse to overuse of digital media — play a major factor, as do lack of social connections, worsening health conditions for some of the population and declining trust in the government.

But these are assumptions, Stone explains. “It’s hard to pinpoint the exact causes, especially if there isn’t specific causal evidence.”

World happiness has actually fallen in recent years, according to the report, driven by a sustained downward trend in India, which some experts attribute to the swell in its population. There has also been a recent, widespread upward trend in negative emotions such as worry, sadness and anger, particularly in Asia and Africa.

Unsurprisingly, the world’s least happy countries tend to be places where citizens face challenges to their health, lack access to education, have unstable governments and face economic challenges. Countries at the bottom of the list are Rwanda, Tanzania, Afghanistan, Central African Republic and South Sudan, which comes in last.

But that doesn’t tell the whole story, says Assistant Professor of International Relations Brett Carter, who studies politics in Central Africa, particularly in countries ruled by nondemocratic governments.

“We’re all the same,” Carter said. “We all want to provide for our families and we all feel profound sadness when we watch our loved ones live difficult lives.”

He points to a number of stories of resilience in the face of hardship. For instance, a Cameroonian entrepreneur co-founded a mobile health platform to help mothers and pregnant women access medical advice in remote, rural communities.

“One way to think about that is whenever governments fail to provide social safety nets, communities often respond by coming together and compensating for shortcomings,” Carter said.

But, where living standards are low, maternal and child mortality rates are high, safety nets are few and far between, and governments focus on their own self-interests over the well-being of citizens, finding happiness will continue to be a challenge.

Additional reporting by Emily Gersema.

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2019/Winter 2020 issue >>