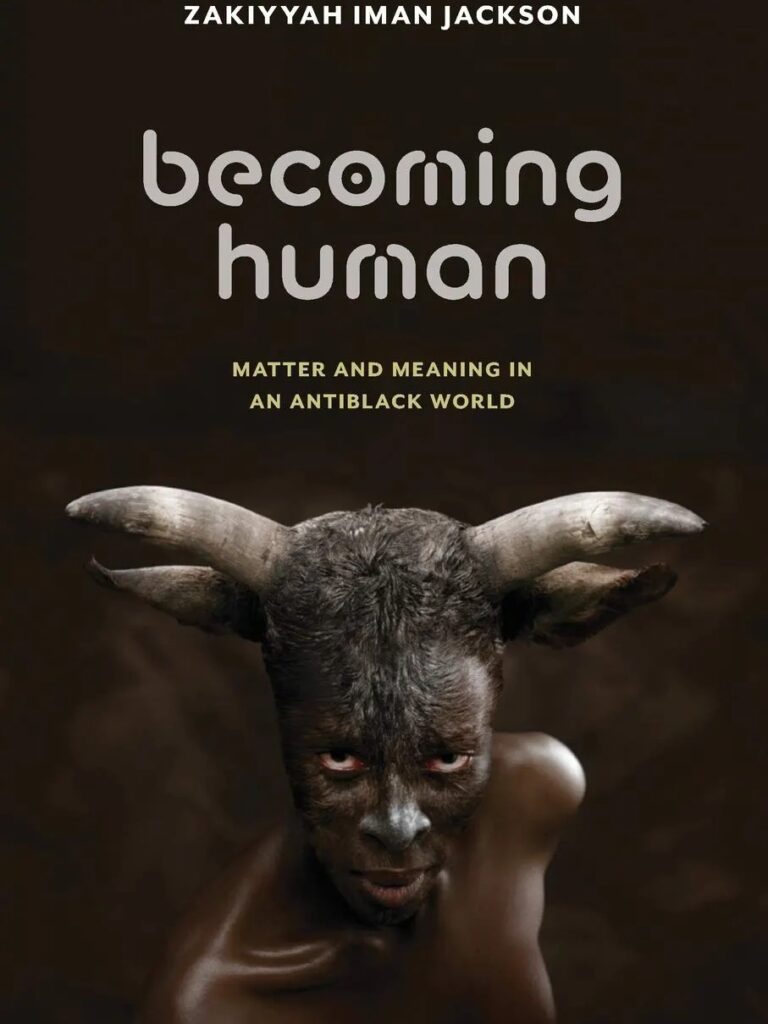

Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World

Rewriting the pernicious, enduring relationship between blackness and animality in the history of Western science and philosophy, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World breaks open the rancorous debate between black critical theory and posthumanism. Through the cultural terrain of literature by Toni Morrison, Nalo Hopkinson, Audre Lorde, and Octavia Butler, the art of Wangechi Mutu and Ezrom Legae, and the oratory of Frederick Douglass, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson both critiques and displaces the racial logic that has dominated scientific thought since the Enlightenment. In so doing, Becoming Human demonstrates that the history of racialized gender and maternity, specifically antiblackness, is indispensable to future thought on matter, materiality, animality, and posthumanism.

Jackson argues that African diasporic cultural production alters the meaning of being human and engages in imaginative practices of world-building against a history of the bestialization and thingification of blackness—the process of imagining the black person as an empty vessel, a non-being, an ontological zero—and the violent imposition of colonial myths of racial hierarchy. She creatively responds to the animalization of blackness by generating alternative frameworks of thought and relationality that not only disrupt the racialization of the human/animal distinction found in Western science and philosophy but also challenge the epistemic and material terms under which the specter of animal life acquires its authority. What emerges is a radically unruly sense of a being, knowing, feeling existence: one that necessarily ruptures the foundations of “the human.”

Forum Contributors

Penelope Deutscher

Northwestern University

Tavia Nyong’o

Yale University

Joshua Chambers-Letson

Northwestern University

Penelope Deutscher

The many debates into which Becoming Human intervenes include post-Foucauldian interest in the interrelation of power’s multiple techniques and forms, a relationality to which Zakiyyah Jackson adds the term “ontological plasticization” (Jackson 2020, 71).[1] Jackson and others have pursued a question also explored (less richly) by Michel Foucault: how these forms of power cohabit or inter-penetrate? More specifically, what role does the entangled relationality of diverse forms of power play in effecting racism’s violence and ontocide? As used by Jackson, the term plasticity[2] refers to the “dynamic motility of antiblack arrangement” (Jackson 2020, 72, 73) and is routed less via Malabou than through Saidiya Hartman’s use of the term to characterize concurrent recognition and denial of humanity under slavery (Hartman 1997, 119; Jackson 2020, 219, n. 2).

Foucault, whose work contains a number of accounts of the interrelationship of different forms of power,[3] is also an intermittent reference. But for all that he makes mention of domination, as Jackson points out, he was far less inclined than have been Jackson (and others, including Banu Bargu, Saidiya Hartman, and Jasbir Puar) to understand the very inter-penetration of diverse forms of power (among these: sovereign, discipline, securitizing, bio- and necro-political forms of power, pastoral, neoliberal and debt governmentality, states of exception, ontological terror) as critical to understanding the complexity of domination specifically, still less as the complexity of racial domination.[4] Also prominent in this emerging cluster of conceptual problematics is the Deleuzian term assemblage.[5] It, too, is annexed by a number of post-Foucauldian theorists to revisit domination’s multiplicity of interrelated forms, all in a way that gives prominence to paradox and contradiction within this interrelationality.

All these elements are at work, for example, in Banu Bargu’s analysis of how disciplinary, sovereign, and biopolitical forms of power interact. Their very relationship should itself, she argues, be understood as a further, distinct form of power, “biosovereignty” (Bargu 2016, 84). Moreover, to this nexus corresponds the similarly specific form of resistance she has termed “necroresistance.” To the difference of Jackson, Bargu reserves the term “resistance” for concerted actions arising from individual or group agency (Bargu 2016, 83, 85-6). By contrast, in the diversity of resistant embodiment and resistant aesthetic production explored in Becoming Human, Jackson broadens considerably the scope of resistance and the transformation with which agency is associated (now extended to the biology of antiblackness’ biopolitical formations). Moreover, her interest in Hartman’s use of the term plasticity allows closer attention to the materiality of domination’s contradictory or paradoxical forms.

When Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection speaks to how the immediate conditions for ex-slaves (new laws restricting freedom of movement, enforcing work contracts, deflating wages, necessitating debt, an extensive system of penalties, fines, debt, and arrest for minor infractions, and the extensive use of prisoner labor) undermined the ability to realize the promoted norms of autonomous individuality and self-improvement, it could be said that different forms of power, including disciplinary norms for the conduct of freedom and sovereign strategies of domination impose contradictory expectations. But this very phenomenon intensifies the viciousness of racial domination, in an environment that coerces and renders inevitable a “failing” conduct of freedom that is also deemed blameworthy. Jackson amplifies the potential effect of turning to the term plasticity in this context. Here, she is not referring to a more general “movement and passage between the formation and dissolution of form” (Jackson 2020, 226n39, citing James 2012) but to a more specific “potential that can turn against itself” (Jackson 2020, 72, 73). This potential has at least two overlapping dimensions: on the one hand, racial domination’s drive to transform blackness maximally into a resource of extraction within the limits of viability (Jackson 2020, 10, also discussing Smallwood 2007, 36). On the other hand, Jackson gives attention to how the very multiplicity of forms of power effecting racial domination can also give rise to dissonance and conflicting effects. A coincidence of aims does not preclude a conjunction of contradictory techniques. And since “power only takes direction from its own shifting exigencies,” (Jackson 2020, 10), the complex cruelty of domination will sometimes have “chaotic results” (Jackson 2020, 10).

This is explored in Becoming Human’s brilliant reading of Toni Morrison. Insofar as sovereign domination both aimed to reduce slaves to animality while coercing sufficient humanity to extract productive work and reproduction, Beloved speaks to how its own technologies can undermine this aim: an enslaved man might come to be mesmerized by the greater autonomy of a rooster, in a competition concerning prestige and masculinity whose incoherence is also eloquent. It engages and confuses the hierarchical binaries of gender, animality and humanity it also supposes. Scene of torture might destroy the capacity for interaction, speech or work. Brutal conditions intended to animalize might produce a form of maternal care whose expression is infanticide, disrupting control or profitability.[6]

Jackson revisits black maternity differently in “Organs of War.” Discussing the relationship between racial violence, debilitated environments, and the biological milieux of reproduction, she argues that the necropoliticized reproductive environments of racial domination should not just be seen in terms of debilitated effect. When the biological materiality of racism in the United States has included higher adult and infant mortality, or the increased likelihood of cancer, “biology’s agency is not prior to or independent of the biopolitical order but embedded in biopolitical systems” (Jackson 2020, 199). The toxic environments of antiblackness also produce bodily environments, with the result that the latter are not only the passive recipients of power’s effects. Rather, Jackson describes biological environments in which the “very agency of the body produces the conditions of possibility for the racially disparate gutting of bodies by reproductive tumors and cancerous cells” (Jackson 2020, 199).

So, when Jackson specifies, “If the aim is to argue that blackness is nothingness and to demystify the machinations that make blackness appear as something, my aim is the opposite: I maintain that blackness, and the abject fleshly figures that bear the weight of the world, is a being . . . and I aim to reveal and unsettle the machinations that suggest that blackness is nothingness” (Jackson,2020,85), a number of interventions into contemporary debates are clustering together at this point. Jackson’s lexicon includes being, matter, and power. Where ontocide would refer to racial domination’s capacity to effect blackness’ status of non-being (an ontological status in which being is intertwined with forms of power associated with domination and sovereign decision), Jackson’s agreement that racial domination requires contradictory and mutually unsettling forms has a different result:

Antiblackness — if it is a system rather than a ground — will have to confront that which exceeds its structure of stable replication and confounds its adaptive operations, which are the very conditions that generate mutational possibility. (Jackson, 2020, 214)

This is to locate subtle forms of resistance at the level of biological formations. Racial ontocide’s contradiction between being and blackness (Warren 2018), also works though contradictory effects arising from the sometimes conflicting techniques required by a plurality of forms of power. These techniques are corporeal (at once presupposing and producing the bodies that are molecular, individual, and multiplicities). To locate contradictory effects within the capacity for mutation is, for Jackson, to excavate something other than non-being. When racism relies on multiple techniques of power coalescing as a corporeal relationality, that relationality can also be understood as a form of mutual interrogation. The recent critical reflection in Miller’s Embryos and Alphabets (Miller 2017) on new materialist theorization of biological agency that still assigns “intelligent” agency elsewhere, might see an alternative in Jackson’s account of the paradoxical biology and contradictory reproductive environments of racial domination. In Becoming Human, to speak of the paradox, contradiction and even the chaos of corporeal forms and states can also be a means of acknowledging them to be astute.

NOTES

[1] “Slavery’s technologies were not the denial of humanity but the plasticization of humanity,” (Jackson 2020, 71).

[2] See Jackson, 2020, 10 and 71-3 for her differentiation from Malabou’s usage of plasticity.

[3] See particularly his College de France lectures: Security, Territory, Population and Society Must Be Defended. In Society Must Be Defended Foucault mentions the “penetration”, “permeation” of these forms of power, in Security, Territory Population, he refers to their coincidence and also to their transformation, taking up, redeploying, reactivation of each other (Foucault 2003, 241; Foucault 2007, 8-9).

[4] While emphasizing in a footnote that she is “theorizing what Foucault would not, namely domination,” Jackson points out that while for Foucault domination is a calcified form poorly adapted to analyzing power’s multiple relationalities, he does sometimes “allow for some modicum of relational capacity and distributed agency to exist in domination” (Jackson 2020, 234).

[5] Used, for example by Bargu (2016), Jackson (2020), Puar (2017), and Gago (2017).

[6] Adding to the dialogue, Weinbaum speaks to Morrison’s (deliberately “true but not factual”) choice in Beloved to have Schoolteacher abandon Sethe, and her sons, deeming them to be past the point from which value can be extracted, as contrasting with the historical account of Margaret Garner who was recaptured along with her sons, and returned to slavery (Weinbaum 2019, 90).

Bibliography

Bargu, Banu. 2016. Starve and Immolate: The Politics of Human Weapons. New York: Columbia University Press

Foucault, Michel. 2003. Society must be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-76. London: Picador.

Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977-1978. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Foucault, Michel. 2014. “Bio-history and Bio‐politics,” Foucault Studies 18 (2014): 128‐130.

Gago, Verónica. 2017. Neoliberalism From Below: Popular Pragmatics and Baroque Economics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hartman, Saidiya. 1997. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman. 2020. Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World. New York: New York University Press.

James, Ian. 2012. The New French Philosophy. New York and London: Polity.

Miller, Ruth A. 2017. The Biopolitics of Embryos and Alphabets: A Reproductive History of the Nonhuman. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Puar, Jasbir. 2017. The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Smallwood, Stephanie E. 2007. Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa American Diaspora. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Warren, Calvin. 2018. Ontological Terror: Blackness, Nihilism, and Emancipation. Durham: Duke University Press.

Weheliye, Alex. 2014. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham: Duke University Press.

Weinbaum, Alys. 2019. The Afterlife of Reproductive Slavery. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Tavia Nyong’o

Becoming Human arrives at a time when we urgently need to rethink the humanist and posthumanist terms that constrain even our most radical proposals to overthrow the present order. Although critical theory has long been skeptical of anthropocentrism, and although political praxis has become increasingly attuned to the existential threat of the anthropocene, (post)humanist discourse in general has failed to unflinchingly confront the antiblackness that underpins discourses of the human. Even more devastatingly, the interventions of black feminism have yet to be fully acknowledged as critiques of the universalizing tendencies that seek to constrain their relevance to the local and identitarian. Zakiyyah Jackson’s Becoming Human takes up this necessary task. At a theoretical level, it holds the promise of breaking open a quickly calcifying debate between critical race studies and (post)humanism over the polemical uses of the figure of the animal as a target of humanitarian concern. At a political level, it renews the scope and urgency of black feminist study as the critique of an antiblack world. And it accomplishes both its theoretical and its political task by intervening decisively into the philosophy of plasticity—a term which has grown almost into a critical fetish in recent years—and grounding it in the speculative and abolitionist project of black studies.

Becoming Human achieves all this with both care and rigor, attending to art and literature that are, in Christina Sharpe’s resonant phrase, “in excess of the matrix of antiblackness and its constitutive forms of the human, animal, gender, and matter.” At a moment when the matter of black life is again shaking the neoliberal order to its core, proving once again that spectacularized pain and suffering can never, in and of itself, redeem the humanist project, Becoming Human is a deep dive into the radical alternative imaginary through which African diasporic aesthetics challenge and displace white supremacist and Eurocentric hierarchical orderings of the human. In so doing, Jackson joins recent thinkers like Denise da Silva, Jayna Brown, Alexander Weheliye, Fred Moten, and Kandice Chuh, all of whom have argued powerfully against the pursuit of sovereign individuality as a remedy for historical and present-day dehumanization, and have instead looked to a radical aesthetic grounded in social and relational figurations. Jackson’s detailed readings of speculative art and literature advance this project through her singular and virtuosic erudition: hers is an intelligence that encompasses without recapitulating, that explains without reducing, and that, above all, affirms the complexity of life without succumbing to a vague or sentimental vitalism.

For a long while now, the black radical tradition has asked the question: how do we live with the seeming permanence of antiblack violence? One recent answer has been to embrace world-annihilating forms of nihilism and pessimism, and to seek to wield these forms of negativity to extricate black critical thought from any lingering residual attachment to either liberal or radical humanism. Becoming Human intervenes within this contemporary debate over critical negativity by decisively insisting that the terms of the debate must include sexuality, reproduction, and gender. But it insists equally that these terms cannot be thought of in humanist or white-normative frameworks. The speculative turn that Jackson makes is therefore not one into escapist fantasy, as skeptics often assume. Black queer feminist speculation, to the contrary, is a crucial form of thought experiment, a necessary propaedeutic to any future collective project of unbecoming human.

But what can aesthetic forms like speculative fiction teach us about the violence of liberal conceptions of the human in racial capitalism? How can we possibly think or imagine when the policeman’s boot is on our neck? Becoming Human understands this crisis as a crisis of meaning, and enjoins us not to surrender our critical faculties in the face of annihilatory violence. We can see this violence at work in the present moment, in which the “sovereign” rights of “citizens” to peacefully assemble are being invidiously contrasted with indefensible and criminal acts of looting and the destruction of property. Violent police suppression of protest is being justified as necessary to preserve the sanctity of property relations that, Jackson reminds us, are grounded in the property relation that was slavery. In her reading of Octavia Butler’s story “Bloodchild,” Jackson charts a path beyond this liberal humanist subject, showing how Butler “replaces it with a radical conception of subjectivity that sees generative possibility” in the relational (Jackson 2020, 140). Butler’s tale of interspecies symbiotic dependency between humans and an insectoid alien species, Jackson argues, dismantles the ruse of the “self-determining and self-defining” subject, showing it to be grounded in gendered fantasies that “reject the master’s authority but not the property relation” (Jackson 2020, 143). In the place of this self-determining and autonomous individual, Jackson’s reading derives a black feminist political ontology from “Bloodchild,” one in which “the political is now the ever-expanding processual field of the relational dynamics of life in ceaseless flux and directionless becoming” (Jackson 2020, 157).

Joshua Chambers-Letson

Vertigo. A disordering, whirling sensation. A loss of equilibrium, loss of bearing, loss of a foothold in the world. The loss of a world coming undone. Vertigo, as Zakiyyah Iman Jackson describes it in Becoming Human’s second chapter, is “that sense of unhinged reality, a communion with death and that realm which exceeds life [and] seems to threaten a total loss of self as incommensurable metaphysical frameworks and sensory maps meet” (Jackson 2020, 114). But, here, this sense of “unhinged reality” is not merely some abstract conceptualization of “being in the world”: it is the sense of blackness, or even black people’s experience of being within a world constituted through the registers of antiblackness. As Jackson describes it in her reading of a speculative novel by Nalo Hopkinson), vertigo is a state that “functions as a metaphor for the ‘onto-epistemological’ predicament of black mater, as mater, as matter under conditions of imperial Western modernity or the conception of Man within the terms of a taxonomical telos” (Jackson 2020, 83).

The density of this passage requires a slow unpacking, but notice first how the encounter with Jackson’s prose may produce a vertiginous effect for the reader (or listener). In both of these quotations one becomes entangled within beautiful, dark, difficult and revelatory language from a theoretician who is fully in grasp of her powers such that the experience of reading Becoming Human affects a vertiginous pull towards the letting go of an idea of the world in which matter and being are determined by and determinative of antiblackness. Giving up on an antiblack world will, indeed, produce a sense of vertigo. But, as the work of one of Jackson’s chief interlocutors (Octavia Butler) routinely reminds us, the teleology of this world (which is to say, of this antiblack world) is almost certainly on a collision course with catastrophic annihilation. Vertigo, as an alternative to a telos that keeps black life on a trajectory towards death, becomes a constricted but no less immanent condition of possibility.

The vertiginous pull of Becoming Human is not a fall into the abyss of nihilistic negation. It’s the experience of accompanying Jackson as she weaves together a new language for speaking of the way that, as she writes, “black mater holds the potential to transform the terms of reality and feeling, therefore rewriting the conditions of possibility of the empirical” (Jackson 2020, 39). Working with interlocutors that include Hopkinson, Butler, Sylvia Wynter, Hortense Spillers, Audre Lorde, Wangechi Mutu, Toni Morrison, Frank Wilderson, Alex Weheliye, and Saidiya Hartman, among others, Jackson insists that antiblackness is not just a thing-in-the-world, it is the environment: an “ecology of violence—pervasive and chronic” (Jackson 2020, 208). Antiblackness isn’t just the air we breathe, or can’t breathe (depending on the circumstances), it is also the particulate, molecular stuff of being-in-an-antiblackworld.

Playing with the aural resemblance between matter (referring to a thing, a physical substance, a concept, and, ultimately, the stuff of being) and mater (the mother), Becoming Human insists that blackness and the black mater(nal) are not simply sites of negation or the constitutive limits against which Man and his order of dominion is defined.[i] Through a critique and deposition of the “prevailing conceptions of [and racialized cleavages between] ‘the human’ [and the animal]” within Western science and philosophy, Becoming Human shows us how “Blackness has been central to, rather than excluded from liberal humanism: the black body is an essential index for the calculation of degree of humanity and the measure of human progress” (Jackson 2020, 46). Mere inclusion or recognition within the ranks of humanity will always be insufficient (may, indeed, reify the very onto-epistemological order that constitutes itself by and through antiblackness), insofar as black being is used as a matrix and metric for the definition of the orders of humanity (quite literally, within the taxonomic charting of a continuum between animal and human life in the history of Western science). Nor will Jackson will not let us rest in an abstract articulation of blackness that delinks it from the experiences of black people and black femmes, in particular. Indeed, where blackness is a central antagonism at the heart of liberal humanism, “black female flesh” and the black mater(nal)function as the paradigmatic, zero-sum ontological index on, against, and through which (depending on how she is needed) Man is defined such that, “the black maternal figure functions as a signifier that apportions and delimits Reason and the Universal” (Jackson 2020, 108).

Becoming Human rigorously and principally insists that this world is not only insufficient for the fostering of black life, but is in fact a necropolitical order that maintains itself by fixing black being on a telos towards death. Where antiblackness is a constitutive component of the making of the world as such, Jackson will not settle for merely changing or reforming this world; she wants something else entirely. But this is not to be mistaken for the howling of that immature, greasy haired, white leftist boy anarchist (or graduate student) as he stages his call to tear this world apart with no care for how many black people pay the cost or bear the burden of his oedipal rage against his father’s machine: a machine built by coerced black labor, using black blood as its fuel.

Where Xena Warrior Princess battled the chthonic gods of a dying Hellenic ideology, Zakiyyah Warrior Theorist goes toe to toe with the death-dealing prophets of the En-White-enment (a history of Whiteness universalization and hegemonic dominance as embedded within, but not fully contained by or reducible to the Enlightenment). Battling the bros of imperial Western modernity—from Hegel and Darwin to J. Marion Sims, Hans Haeckel, and Heidegger—she slays left and right as she reveals their production of and universalization of Man (and the taxonomic orders of “humanity” and “animality” that follow from Him), in order to show how these epistemological and ontological systems fix black matter and the black mater(nal) as the “enabling condition” of an antiblack concept of the world as such. The word “fixes” may be misleading, as Jackson defines the appropriation of black(ened) humanity in modern imperial Western thought as a form of plasticity, whereby “blackness is experimented with as if it were infinitely malleable lexical and biological matter, such that blackness is produced as sub/super/human at once, a form where form shall not hold; potentially ‘everything and nothing’ at the register of ontology” (Jackson 2020, 3). This experimenting with blackness, and the black mater(nal) is both literal and figurative—as is paradigmatically exemplified in J. Marion Sims’ brutal experimentation on enslaved women during the founding of modern gynecology. The impassioned demand to make a seat at the table for black people in this world reveals that the seat has always been there. The seat is the cornerstone of the table, in fact: in it sits Henrietta, Lucy, Anarcha, Betsey as Sim’s experiments on their flesh with no anesthesia applied. A reading of Becoming Human makes it clear that asking for standing in the world will only ever reconstitute the world. What’s needed is a sense of vertigo.

For many white people in this occupation we call a country, the feeling of the last week, of the last few months, and of the last few years has been, precisely, the vertiginous experience of losing one’s footing in a world spinning apart. One could almost say, “welcome,” but this is not—this moment is not, no matter how much they post on Instagram about it, about white people—nor is the feeling of vertigo being experienced by the nonblack world the same mode of vertigo described here: though they’re not unrelated. Becoming Human reflects the fact that for black folk living in the wake of slavery’s historical rupture, this vertiginous sense dates back at least four hundred years. It is the very experience of blackened being and being not that makes possible the telos of imperial Western modernity. Becoming Human is thus a love letter to and for black people, whose vertiginous black powers keep opening up the possibility of possibility for blackened being. As Jackson writes, in language with which I’ll conclude: “Vertigo, here, is a measure and means for the disordering and inoperability of a metaphysics that takes the black mater(nal)’s nonrepresentatibility as its enabling condition… Vertigo is both the apprehension of unlived possibilities and the salvific irruption into consciousness of discredited sensation, of other ways of living, other modes of life that provide a dizzying sense of vivifying potentiality” (Jackson 2020, 120).

NOTES

[i] Through her engagement with, and deconstruction of the work of the paradigmatic philosophers and scientific minds of “imperial Western modernity,” Jackson’s text (to use her own description of Hopkinson’s novel) “performs a critique that shatters the globally hegemonic metaphysics of the world—indeed, of a world relation—[and] that transversally voids the black and the animal and their respective worlding(s).”

Zakiyyah Iman Jackson

REPLY

Iwant to express my gratitude to Tavia Nyong’o, Joshua Chambers-Letson, and Penelope Deutscher for their thoughtful reflections on my book, Becoming human: Matter and meaning in an antiblack world (Jackson 2020). It is an honor for my work to receive this manner of attention, and I have learned a great deal from their generous engagements. This forum requires brevity, so I have decided to approach the task of responding by continuing the conversation and taking up a few of the keywords that called out for further comment, in particular humanitarianism, plasticity, and representation.

In the book, I stressed that the categories of “the human” and “the animal” are not sequential but co-constitutive. Since its inception, which some have attributed to Descartes and his cohort, “the animal” has been conceived of with black(ened) people as an integral part of the term’s meaning and function: blackness distributes value and undergirds a racially striated and hierarchical mode of life vis-à-vis the self, world, and environment. Similarly, the mode of life we call human has foundationally imagined black(ened) people as integral to its hierarchical delineation of reason and sensorium, as an at times nullified form, but more commonly as its “lowest” form: deviant, pathological, teratological, and criminal, and thus a human form without entitlement to rights and protection. Sense and reason are both hierarchically arranged via the relational violence of antiblackness. Thus, the mythic function of blackness is not simply to define by negative relation but to give form to both categories: human and animal, such that black(ened) people are constitutive of both categories, especially when the two are hierarchically opposed or teleological.

In Becoming human, I reinterpret Enlightenment thought not as black “exclusion” or “denied humanity” but rather as the violent imposition and appropriation—inclusion and recognition—of black(ened) humanity in the interest of plasticizing that very humanity, whereby “the animal” is one among many possible forms blackness is thought to encompass. To be included in such a way is to be dominated and circumscribed precisely as Chambers-Letson notes: “Mere inclusion or recognition within the ranks of humanity will always be insufficient (may, indeed, reify the very onto-epistemological order that constitutes itself by and through antiblackness), insofar as black being is used as a matrix and metric for the definition of the orders of humanity (quite literally, within the taxonomic charting of a continuum between animal and human life in the history of Western science) … The impassioned demand to make a seat at the table for black people in this world reveals that the seat has always been there. The seat is the cornerstone of the table, in fact: in it sits Henrietta, Lucy, Anarcha, Betsey … Becoming Human makes it clear that asking for standing in the world will only ever reconstitute the world.” I argue that when one examines the history of science, law, and philosophy, black(ened) female flesh persistently functions as the constitutive limit case of “the human” and is its matrix-figure, due to the central role reproduction plays in determining species demarcation and the racialization of that function. In other words, the threshold of the human has been determined by how the means and scene of birth are interpreted. The black female figure was, and I argue remains, the fulcrum of categorical distinction writ large.

Ontologized plasticization is not interchangeability, replaceability, or exchangeability. It is not the conceptualization of how a good or asset is understood as being of equal value to another. If we consider the history of antiblackness, for instance, we might recall how a slave was commoditized alongside, and made exchangeable with, a cow or a horse. This familiar image is related to fungibility, our thinking on which is indebted to Saidiya Hartman’s indispensable Scenes of subjection, but ultimately “fungibility” is not what I mean by ontologized plasticization (Heartman 1997). As a concept engaged with the new materialisms, I am interested in what is called hylomorphism or the form-matter distinction. Ontologized plasticization, in my work, is a conceptualization of form itself rather than a conceptualization of how a form is taken up within the logics of law, economic markets, or political economies. In other words, it is not a conception of the commodity and its uses. It is a conceptualization of property—but of the properties of form.

Ontologized plasticization is not defined as the unnatural ordering of man and beast. It is a mode of transmogrification whereby the fleshy being of blackness is experimented with as if it were infinitely malleable lexical and biological matter—a form where form shall not hold—such that blackness is produced as human, subhuman, and suprahuman at once. The “at once” here is important: it denotes immediacy and simultaneity. Blackness, in this case, functions not simply as negative relation but as a plastic fleshy being that stabilizes and gives form to “human” and “animal” as categories—precisely via blackness’s inability to access conceptual and material stability other than that of functioning as ontological instability for the reigning order. To put it another way, my concept of plasticity maintains that black(ened) people are not so much dehumanized, cast as nonhumans or as liminal humans, nor are black(ened) people framed as animal-like or machine-like or simply exchangeable with these nonhuman forms; rather, they are cast as sub, supra, and human simultaneously and in a manner that puts being in peril because the operations of simultaneously being any-thing and no-thing for a given order constructs black(ened) humanity as the privation and exorbitance of form. The demand for willed privation and exorbitance that I describe does not take the structure of serialized demands for serialized states but demands that black(ened) humanity be all forms and no form simultaneously; human, animal, machine, object, and….

In other words, plasticization, here, is a mode of ontologizing not at all deterred by the self-regulation of matter or its limits, nor by what Catherine Malabou has described as “the fragile and finite mutability” of the form we call black (Malabou 2010). Black studies scholars have often interpreted the predicament of black(ened) being in relation to either liminality (movement from one state to another state) or interstice (being in between states) or partial states (Spillers 1984; Wynter 2003; Weheliye 2014). What I am suggesting is that these appearances are undergirded by a demand that tends towards the fluidification of state or ontology. This demand for statelessness collapses a distinction between the virtual and the actual, abstract potential and situated possibility, whereby the abstraction of blackness is enfleshed via an ongoing process of wresting form from matter such that antiblackness’s materialization is that of a de-materializing virtuality. We must think critically about the enthusiasm for ontological slippage in much recent posthumanist, ecocritical, and speculative-realist critical theory when that very imagination has been conditioned by both a racialized phantasy of bound(ary)lessness that recognizes the protean capacities of the flesh only to boundlessly exploit it and what Deutscher searingly and aptly describes as “racial domination’s drive to transform blackness maximally into a resource for extraction within the limits of viability” and if by chance beyond viability, it typically incurs no consequences for the extractor. What is at stake is the definitive character of form, its determinacy or resistance, which is potentially fluidified by a willed excess of polymorphism and the violent estrangement of form from matter.

Regarding the function of blackness in humanitarian discourse, raised by Nyong’o, a rather immediate image comes to mind: the book cover of Anna Sewell’s Black beauty (Sewell 2012). In the nineteenth century, with slavery increasingly under pressure from both abolitionists and the multi-scalar rebellions of enslaved people on behalf of themselves, legal reform emerged as an alibi for the irremediable. Terror was subject to regulation rather than annulment. This legalistic approach would calculate and legitimate the humane use of force. Thus, palliation sheltered brutality by providing it an alibi: morality and related fictions of gentility and kindness. White bourgeois domesticity now rendered as stewardship and care was given a carte blanche mandate to domesticate all those thought incapable of governing themselves, in particular the enslaved and animals. Enter Sewell’s Black beauty,initially subtitled, “The autobiography of a horse.” The subtitle drew its inspiration from the slave narrative genre, a point underscored by its marketing as “The Uncle Tom’s Cabin of the horse” in 1890 by George Angell, lawyer and founder of the United States’ second animal protection organization (Grier 2010). Drawing on many of the literary devices of Stowe’s novel, Sewell firmly established the potency of slave abolitionism as an analogue for animal advocates. Advocates for the humane treatment of animals took direct inspiration both from abolitionism as a rhetorical platform and its related literary genre. These same advocates also embraced strategies of reform popular among slaveholders and white abolitionists—in particular, a palliative approach to white domination and violence, albeit differentially articulated. The figure of the slave was and continues to be the ur-text of the humanitarian and the humane, commonly instrumentalized by law and advocacy campaigns and quickly dispensed with in efforts that seek to reform. Law denied the rights of motherhood to the enslaved even as it assigned her a peculiar kind of reproductive function, to be the model for commoditizing life over and over again: animal life, artificial life, the corporation, intellectual property and… and…. Thus, the instrumentalization and containment of the slave’s cataclysmic claim is essential to the maintenance of the existing order.

One last point. I maintain that our (human) being does not precede what we say about ourselves, or what is said about us. Bios and mythos are not sequential (Wynter 2001). When biology and culture are understood as sequential, we will inevitably find blackness, in particular Africanness, embalmed in the past, in an earlier stage of development. The myths we produce, the stories we tell, the images we create are inextricable from what they purport to reference, even when they are composed by societal phantasy and perception is arranged by antiblackness. Representation is not re-presentation or mimesis; it is a doing, a making, a worlding that in turn makes us. In Becoming human, the term I use for this is “measurement.” Antiblackness is an aesthetics that cuts the material realm of reality. To evoke Dionne Brand, antiblackness introduces a “tear in the world” that is determinative of world and flesh (Brand 2012). And if black(ened) people have functioned as tools for this order, it is important to remember that tools are always excessive to how they are defined and used by a human perceived as sovereign and masterful.

Bibliography

Brand, Dionne. 2002. A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging. Vintage Canada.

Grier, Katherine C. 2010. Pets in America: A History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press Books.

Hartman, Saidiya. 1997. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman. 2020. Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World. New York: New York University Press.

Malabou, Catherine. 2010. Plasticity at the Dusk of Writing: Dialectic, Destruction, Deconstruction. New York: Columbia University Press.

Sewell, Anna. 2012 Black Beauty. Oxford: Oxford University Press (1877).

Spillers, Hortense. 1984. “Interstices: A Small Drama of Words.” In Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, edited by Carole S. Vance, 73-100. Boston, London, Melbourne and Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Weheliye, Alexander G. 2014. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham: Duke University Press.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Towards the Sociogenic Principle: Fanon, Identity, the Puzzle of Conscious Experience, and What it is Like to e ‘Black’.” Hispanic issues: National identities and Sociopolitical Changes in Latin America 23 (2001): 30-66.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, its Overrepresentation—An Argument.” CR: The New Centennial Review 3 no. 3 (2003): 257-337.