The transformation and social implications of China’s underground recycling industry

A curious graduate student living in Beijing in 1995, Joshua Goldstein was fascinated by the throngs of people who passed him every day on bicycles piled high with what appeared to be every kind of trash. One afternoon he hopped on his bike and followed them. The short trip led to an erratically organized and filthy garbage heap, where vendors paid a pittance for old paint cans and empty bottles sorted according to what they had once contained — soy sauce here, vegetable oil there.

“That first day I was cautious and spoke only to one woman, who led me through the stalls and told me about how the underground recycling industry worked,” Goldstein recounted. “I got shy when the police approached me and went away.”

At the time, Goldstein — now an associate professor of history and East Asian languages and cultures — was conducting research for his dissertation on Peking Opera. But Goldstein said he has always been drawn to studying homelessness and poverty, holding hope that he could help raise awareness of the worldwide problem someday.

Wasting time

Goldstein visited the trash market only a few miles from Beijing University regularly during his one-year stay in China in 1995 and received grants to return for a few months in 2000 and 2001. In 2008, Goldstein spent another full year in China observing the social and environmental implications of the country’s recycling industry.

“I was interested in the situation of migrant workers who came to cities from the countryside to participate in this recycling process for subsistence,” Goldstein said. “There would be lines of stalls going on forever that purchased different recyclable products, but in the ’90s the conditions were truly abysmal. It looked as if they lived in giant trash heaps.”

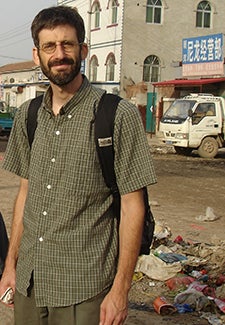

Joshua Goldstein predicts that the recent slowdown in China’s economy may give the government the upper hand in its effort to compete with a successful informal recycling industry.

As time passed, Goldstein noticed a peculiar evolution.

“I noticed the vendors were more and more well off,” Goldstein recalled. “The Beijing government — wanting to maintain control — kept clamping down on them, but could never stop them.”

The markets transformed from a group of people in the middle of garbage heaps, to vendors with yards Goldstein described as “dirty and dingy, but better” — to finally becoming an organized system with separate stalls for each good.

Even the business model had improved, Goldstein said. “Workers actually rented space from the market manager for a monthly fee.”

A trashy story

According to research conducted by Stefan Salhofer and Roland Linzer at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) in Vienna, Austria, China’s underground recycling industry comprises between 3 and 5.5 million laborers — making it among the country’s largest industries. While much of the recycled products processed in China originated locally, there is also an enormous amount of foreign waste that is recycled there.

China manufactures many products to be shipped abroad. It would be a colossal waste of money for the ships to sail back to China entirely empty, so they have devised a system in which unloaded boats transport American waste materials to China for processing. According to Goldstein, it is often cheaper for Americans to send unsorted recycling from Santa Monica to China than to Texas.

While China’s infrastructure for recycling is not superior to that of the United States, Goldstein said, their laborers are more amenable to hand-sorting materials for lower wages. Plastic, in particular, must be painstakingly grouped into dozens of different categories based on its resin type. Only then can it be melted and extruded into pellets, which are reformed into new materials.

Between 3 and 5.5 million laborers are believed to work in China’s informal recycling industry.

Although Goldstein describes plastic recycling as “nasty and toxic,” he believes the informal system in China has the potential to be the lesser of many present evils.

“The goods are being transported on bicycles and then sorted by hand,” he said. “Considering the alternatives, this is a pretty sustainable model. Of course, the only truly effective long-term solution to plastic pollution is on the manufacturing end, not the disposal end. We have to find design alternatives to it.”

Goldstein has published several articles on this research and has accumulated sufficient fodder for a book — but part of what precludes him from finishing is that the plot always thickens.

Since the economic slowdown in China began in the wake of the global financial crisis, the government has focused its energy on fostering an economy that provides services rather than manufactured goods. With less being produced, Goldstein thinks there is a chance the government will have more leverage to shut down the underground industry.

For Goldstein, though, this would be a mistake.

“I don’t understand why they are eliminating something that is, on so many levels, doing an efficient, good job,” he said. “By criminalizing the informal industry, successful business owners aren’t investing in cleaner and more sustainable infrastructure because they could — at any moment — be uprooted.”

Garbage addicted

Instead, Goldstein sees the decades-long transformation of China’s recycling industry as a valuable opportunity.

“From a policy perspective, I argue that the government should work with the informal sector to help mitigate the health and environmental damage,” he said. “Because they have the materials and the labor, China is in an ideal position to set the standard for the world on how to create a safe and sustainable recycling industry.”

Goldstein acknowledges the nontraditional path his scholarship has taken — from analyzing opera to envisioning solutions to one of the world’s perplexing human and environmental challenges.

“It’s been a slow process of learning a different set of skills about survey work, interviewing and documentation to transition the focus of my research,” he said.

For Goldstein, studying trash is addictive.

“I knew as soon as I started that I’d be working on this project for the rest of my life,” he said. “Waste provides a complex and often brutally honest lens through which to see our consumption-driven world.”

And through the process, he has realized he is not the only one with this passion.

“From academics to small-time — and big time — entrepreneurs to street pickers, there are millions of trash-addicts throughout the world,” he said. “In the end, I fell in love with all these humble, hard-working, quirky people who see things a little differently — and aren’t afraid to get their hands dirty.”