Team cracks secrets of undersea chemical reaction that may reduce atmospheric CO2

Scientists at USC Dornsife and Caltech have accelerated a normally slow, natural chemical reaction by a factor of 500, which could store and neutralize carbon in the deepest recesses of the ocean without harming coral or other organisms.

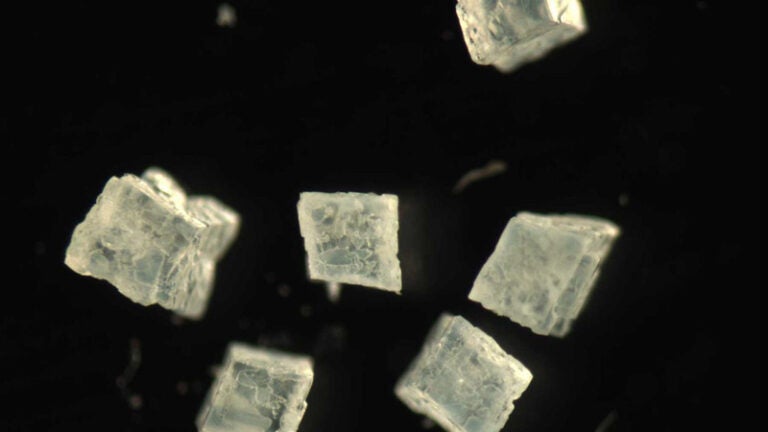

For the first time ever, the USC-Caltech team was able to measure very precisely the reaction rate of calcite, a form of calcium carbonate, as it dissolved in seawater enhanced by a common enzyme called carbonic anhydrase. That’s the same enzyme that maintains the acid-base balance in the blood and tissue of humans and other animals.

“There’s a chemical reaction involving calcium carbonate and carbonic acid we know about, but people studying it before had kind of dismissed it,” said William Berelson, professor of Earth sciences and environmental studies at USC Dornsife and a senior author of the acceleration study.

“This carbonate material that’s all over the ocean floor has been neutralizing ocean CO2 for billions of years. Yet, the uncatalyzed reaction is quite slow. Remarkably, nobody has quite understood how to speed up this process. Now, we’re beginning to figure it out.”

Senior study author William Berelson, professor of Earth sciences and environmental studies. Photo by Peter Zhaoyu Zhou.

Co-principal investigator Jess Adkins of Caltech noted, “The exact mechanism of the buffering by carbonates has been an elusive goal in oceanography.”

Berelson’s lab provided the isotopic measurements crucial to understanding these dissolution rates.

“This reaction has been overlooked,” said Adam Subhas, lead author and a Caltech graduate researcher. “The slow step is making and breaking CO bonds to go from CO2 to CO3. They don’t like to break; they’re stable forms. This is very slow, and nature has figured it out, so it has created an enzyme called carbonic anhydrase to speed it up.”

The findings were published online this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

An antacid for the ocean

Calcium carbonate exists all over the planet’s oceans, from coral reefs near the surface to the shells of dead organisms like plankton that are buried deep below. There is roughly 50 times as much greenhouse gas in the ocean as the atmosphere, causing ocean acidification.

However, when acidified surface waters make their way to deeper parts of the ocean, they are able to react with the dead calcium carbonate shells on the sea floor that neutralize the added carbon dioxide.

This is part of the natural buffering process that allows the ocean to hold such a large amount of carbon dioxide safely, at least in those parts where acidification isn’t touching and eroding structures like coral reefs.

“The dissolution of calcium carbonate in the ocean is what we call in chemistry a buffer. It’s very much like when you take an antacid for an upset stomach because it is neutralizing the acid in your tummy,” Berelson said.

Now, thanks to the USC-Caltech team, this process to safely convert CO2 to bicarbonate that would normally take tens of thousands of years can be replicated in a fraction of the time.

“It isn’t lost on us that this may hold some really important role, sooner or later, in helping mitigate atmospheric CO2,” Berelson said.

About the study

The paper appearing online this week is titled “Catalysis and Chemical Mechanisms of Calcite Dissolution in Seawater.” Co-authors include Caltech geochemistry Professor Jess Adkins, Caltech graduate researcher John Naviaux, USC Dornsife Berelson lab specialist Nick Rollins and Jonathan Erez of Hebrew University of Jerusalem. This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Resnick Sustainability Institute at Caltech, the Rothenberg Innovation Initiative (RI2) and the Linde Center for Global Environmental Science.