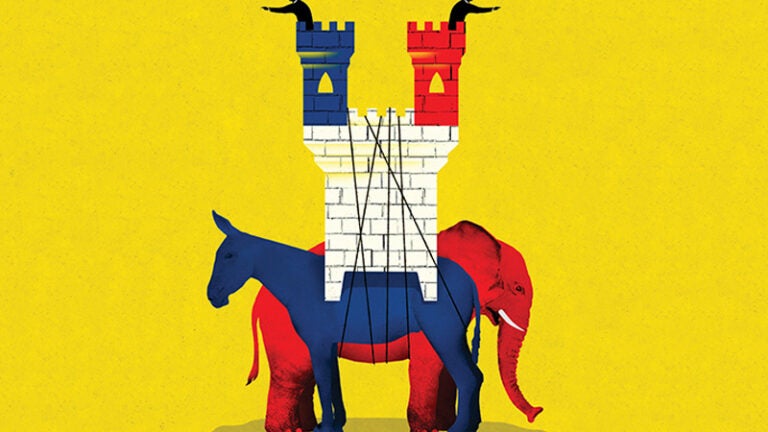

Life of the Party

Despite the fundamental nature of political parties in the daily life of American politics, the U.S. Constitution never even mentions them. Our first president had no party affiliation, and the Founding Fathers were a bit wary of the whole idea and the potential problems these “factions” could cause. But in the last two centuries, political parties have emerged to play a significant role in our system of government and beyond, helping to shape legislation, culture, identity and our ideals as a nation.

This year, the United States has been immersed in an election full of personalities that at times seem larger than the parties they ostensibly represent. Donald Trump’s candidacy as a Republican who has alienated many prominent members of his own party while embracing a stance that is uniquely his own has raised the question of whether this election could realign the electorate and the GOP.

Is there any historical precedent for this? Well, yes and no. But understanding how our dynamic party system works can help us understand whether or not this election is just an anomaly and how much influence it might have on the political landscape moving forward.

The party system is born

Christian Grose, associate professor of political science and director of graduate studies of the Political Science and International Relations (POIR) Ph.D. program at USC Dornsife, studies American politics.

“Even at the founding of the United States, George Washington and the others were really concerned about the idea of political parties,” he explained. “They thought they would be too confining and would create permanent coalitions that would be problematic.”

Looking at the current state of affairs in Congress and election politics, perhaps their predictions weren’t too far off. And yet almost immediately in the early years of our government, informal coalitions began to form within the legislature. It was almost impossible to get anything done in Congress without them, Grose said — after all, a coalition is how something gets passed when there is a large group of people trying to make a decision.

Parties became a fixture in our political system for another reason, too: They came in very handy in terms of organizing and supporting candidates in elections. It was the campaign leading to Andrew Jackson’s presidential election in 1828 that cemented the Democratic Party, Grose noted. The Whig Party emerged in opposition to Jackson’s policies shortly thereafter, sticking around for a little more than two decades.

“The Republican Party came about in the mid-19th century,” Grose said, “and our modern two-party election system really emerged after that.”

It takes two to tango

For better or worse, the two-party system is thoroughly entrenched in the U.S. But why only two? And which is it: better or worse?

“A lot of political science research shows that the number of parties in a constituency [the voters in a specified area who elect a representative to a legislative body] is basically the number of available seats plus one more,” Grose said, adding that this is based on a mathematical proof. We use the “first-past-the-post” voting system, which means voters each choose one candidate and the candidate who receives more votes than anyone else is the winner — and one winner takes all.

“As a result, we tend to have two dominant parties in the U.S.,” he said.

So how is it working for us? On one hand, it could be argued that the two-party system promotes centrism, compromise, political stability and, by extension, economic growth. Governance is simpler, with less fractiousness and fewer radical parties, and without the hung parliaments that can occur with multiparty systems in other countries.

“In a positive sense, it creates two easy choices and it’s not as complex as other systems,” Grose said. “On the other hand, when there are only two major parties, it makes it harder for viewpoints that are less mainstream to be represented. There’s a tendency toward keeping difficult issues off the agenda.”

From this perspective, the two-party system potentially prevents alternative views from getting serious consideration and encourages voter apathy if voters perceive that their choices are limited. And as we’ve seen in the current political climate, the two-party system has often led to vociferous partisanship and impasse. So what is the most efficient system?

“That depends on how you feel about compromise,” said Dan Schnur, assistant professor of the practice of political science and director of USC Dornsife’s Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics. If a person believes strongly in a particular policy position, he said, and doesn’t want to compromise, then the two-party system becomes a source of frustration and inefficiency. “If there are a dozen parties, you can be absolutely pure on the issues that are important to you. With only two major parties, there’s a necessity for compromise.

“But the U.S. system of government is designed to encourage compromise,” he said. “The Founding Fathers put together a system with three branches of government and two houses of Congress in order to protect against what they called ‘the tyranny of the majority.’ So even though we don’t see it that much in 21st-century America, compromise is part of our country’s political DNA.”

The parties they are a changin’

Despite the steadfastness of the two-party system, political parties themselves tend to evolve and change dramatically over time. This happens for a variety of reasons, such as changing attitudes and demands within the electorate as well as the efforts of parties to adopt different positions to try to win elections and reach new voters.

The platform of the Democratic Party, for example, changed considerably over the early 20th century.

“Today’s Democratic Party is identified as being pro-civil rights,” Grose explained, “but prior to [President] Lyndon Johnson and [President] Franklin Delano Roosevelt, it was not considered the party in favor of civil rights. In fact, it was anti-civil rights, a party of whites that was disenfranchising minority voters.

“During the Johnson era and going forward, the Democratic Party tried to adopt more pro-civil rights policies because that’s what the electorate wanted, especially with the enfranchisement of African Americans in the South. So conservative white voters moved to another party, the Republican Party.

“We see patterns like this throughout history where parties take different positions than they would have a generation prior.”

A theory called realignment helps explain how some elections can realign the electorate and alter positions of a party in a way that shifts the balance of power on a lasting basis.

“Realignment has met with some challenges by scholars, but it’s an interesting theory because it helps to explain how things happened in the past,” said Professor of Political Science Ann Crigler. “It helps explain how partisan politics can change rather dramatically.”

A notable period of political realignment occurred in 1932, when FDR was elected by a large coalition of Democrats in addition to other groups of voters not traditionally associated with that party, Grose said.

“You had northern liberals, minorities and southern racist whites all voting for FDR because of the Great Depression. That kind of stuck for the next few elections, with many of the same people continuing to vote Democrat.”

Fractured beyond repair?

The unexpected rise of Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential race has led to a state of turmoil within the Republican Party, as it highlighted existing divisions and wrenched open new ones. Likewise, Bernie Sanders’ ascent posed significant challenges to the Democratic Party as a groundswell of support shifted toward him. There has even been some speculation as to whether, in the face of the disunity stemming from Trump’s candidacy, the GOP might split into two parties.

Historically, however, there are very few examples of this phenomenon in the U.S., called third-party fracturing. This generally occurs when the two dominant parties ignore a critical social or policy issue. The best example of this in our country’s past was the divisive issue of slavery, which was coming to a head in the early 1850s when the Democrats and the Whigs were the two major parties.

Political parties can change dramatically over time due to factors such as changing attitudes within the electorate and parties’ efforts to adopt different positions to attract voters and win elections.

“Neither party was addressing slavery in any serious manner,” Grose said. “They were just trying to avoid the issue because it was very difficult for their coalitions, but it was a massive issue.”

Meanwhile, the nascent Republican Party was promoting the abolition of slavery along with other northern political and economic interests. Significantly, they were the only party to take such a position on slavery.

“When two parties keep a major policy item off the agenda, that’s where a third party could actually emerge to become a second or first party,” Grose said.

This is largely how an ascending third party, the Republicans, overtook the Whigs. While the Democrats were able to maintain cohesion as a party, over the course of the 1850s the Whigs experienced a swift decline due to internal divisions and a lack of national leadership — exacerbated by the disastrous mid-century presidency of Whig Zachary Taylor. Within the space of four years, Gross said, Whigs were supplanted entirely in Congress by Republicans.

Nothing like this has happened since in American history. Even though the candidacy of Donald Trump seems like an anomaly in some ways, even a potential threat to his own party, the demise of the Whig Party cannot really be compared to what is happening with the Republican Party of today.

“There are definitely issues being ignored by both parties now,” Grose said, “but those issues don’t rise to the level of slavery.”

The upside of a splinter

Much more common than third-party fracturing, splintering occurs when a group of voters separates from a major political party due to specific issues, ideologies or, often, economic conditions.

“Under most political circumstances, a third party comes into being in response to an unmet policy need,” Schnur said. “In another system, the Tea Party would not simply be a faction in the Republican Party, it would represent a new party unto itself. Similarly, Sanders supporters would be much less likely to become active parts of the Democratic Party, they’d be more likely to set up a party of their own.

“But in our system, the two major parties have become very talented at recognizing unmet policy needs and adapting themselves to co-opt an emerging ideological strain among the voters.”

In the 1960s, the civil rights movement was “adopted” by the Democratic Party, potentially avoiding the emergence of a third party defined by that issue. A more recent example is the 1992 presidential election in which Ross Perot ran as an Independent. He mounted a highly successful third-party campaign, attracting nearly 20 percent of the vote that November. His major campaign issue was reducing and eliminating the federal deficit, Schnur said, which neither Democrats nor Republicans were devoting much attention to.

“In 1993, the new Democratic president, Bill Clinton, made deficit reduction a very large priority,” he continued. “The following year, Newt Gingrich and the congressional Republicans took over the congressional majority by emphasizing deficit reduction as one of their key issues. By 1996, when Perot ran for president again, his issue had been co-opted by the two major parties and he barely made any impact.”

Major third-party candidates tend to emerge every three or four elections in contemporary politics, said Grose. Some of the more successful 20th-century candidates include Ralph Nader, Ross Perot, John Anderson, George Wallace and Huey Long. While third-party candidates are often a source of splintering, they’re certainly not the only driver, as we’ve seen with Trump.

“What’s interesting about Trump is that he’s a Republican and not a third-party candidate,” Grose explained. “And that has created splintering in the Republican Party, where mainstream Republicans and a lot of people who worked for the Bush administrations are very hesitant to support Trump. Still other Republicans are splintering away to support Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson, a former Republican governor who has garnered up to 10 percent in the polls this year. So what does this mean for the future of the Republican Party?

“If Trump loses and four years from now a mainstream Republican runs again, things could probably go back to normal and perhaps the Republican Party would adopt certain positions that are more in line with what Trump has said, if that’s what voters want,” Grose said, “but it could also just be a one-off. On the other hand, if he wins, that could potentially lead to a realignment where you see people who, having been Republican, would become Democrats.

“That’s another way parties can shift and evolve — due to the candidates that get nominated and the conditions that result.”

Populism: ‘In the eye of the beholder’

Even if some third-party issues end up getting co-opted by Democrats or Republicans, third parties and populist candidates still play a critical role in bringing alternative viewpoints to the forefront and helping the electorate articulate their political desires.

“Populist voices in both parties tend to represent passions within the electorate — matters that voters don’t think are being addressed by the political leadership,” Schnur explained.

The rhetoric of populism — when a politician claims to represent the common people, vowing to protect them against the mainstream elites — is a powerful force for partisan change, Crigler said. This year’s presidential election is noteworthy for having had two impactful populist candidates: Sanders and Trump.

Together with POIR graduate student Whitney Hua and a colleague at Wellesley College, Crigler authored the paper “Populist Disruption: Sanders and Trump Tweets in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Primaries” about the candidates’ use of social media.

“Social media provide a platform that allows populist candidates who normally would not have been successful within the two-party structure to work around it,” Crigler said. “Now the institution of social media allows candidates to communicate more directly with people and allows voters to magnify those messages to their friends.”

Populism, as it lashes out at the establishment and the traditional party structure, has a very strong affective component.

“Emotions are incredibly important in electoral politics,” Crigler said. “You want to be able to tap in to and mobilize people. Emotion is not separate from some kind of cognitive or rational process; it’s fundamentally a part of the way we understand the world. Good politicians know that. So all parties make emotional appeals to voters.”

But is affective politics effective politics?

“Populism definitely has two sides to it,” Crigler said. “It can allow for some political movement and representation of public frustrations, as well as an influx of ideas, which representation and democracy need. But a lot of it can be quite detrimental because it can play on authoritarianism and demagoguery.”

Schnur agreed, illustrating how populism can be fickle.

“Populism is in the eye of the beholder,” he said. “If a voice from the grassroots agrees with you, then they represent a powerful brand of populism. But if that same voice disagrees with you, then they’re irresponsible demagogues.”

Parties as they were meant to be

Beyond any potential to create divisions, political parties also exist in order to facilitate our system of government.

“Parties serve a very vital function,” Crigler explained, “which is to help govern as well as get people elected. The whole structure of the legislative branch is organized around the majority party.”

The majority party controls the seats and chairmanships of committees in Congress, and provides the speaker of the house and majority and minority leaders. It is also the job of political parties to recruit candidates for the next election cycle, register voters and get people involved in politics. Parties groom individuals for elections, offer an organizing structure and work together internally to set an agenda.

The challenge is to keep parties strong and functioning as they are meant to within a democratic government. Super PACs and the growing role of huge wealth in politics represent an outgrowth of the weakening of the parties in recent years, Crigler said. These forces can create undue influence in the political sphere because individuals and groups can fund their special interests and disseminate their message with relatively little accountability.

“With the rise of more candidate-centered politics and reliance on big money and independent groups to help fund candidates, it’s really shifted the role of parties. For a political scientist, that’s a big problem. Because when parties don’t work effectively to recruit candidates, inform voters and coordinate governance, other players fill the gap.”

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2016-Spring 2017 issue >>