Immortal. Beloved.

Her hair is Harlow gold

Her lips sweet surprise …

I’m in the middle of an ’80s flashback.

Her hands are never cold

She’s got Bette Davis eyes.

Singer Kim Carnes’ 1981 smash echoes through my mind. And why not? I’m surrounded by mementos from Bette Davis’ life and film career.

On the wall of Kathryn Sermak’s home office hangs a pastel illustration of Davis, star of such Hollywood classics as Dark Victory, Jezebel and All About Eve, a personal favorite of mine since film school. (I often shamelessly appropriate razor-sharp quips from the film.) Drawn by an ardent devotee, the portrait arrived at Sermak’s mailbox three months after the star succumbed to cancer in October 1989. The eyes seem to follow me throughout the room, as if a villain in some Scooby-Doo cartoon was hiding behind the artwork, watching my every move. Davis’ omnipresence is impossible to avoid. Sermak seems comforted by it.

After all, most of Sermak’s adult life has been caught up in the star’s gravitational pull.

Sermak was student, Girl Friday (a term Davis preferred to secretary), personal assistant, friend, confidant, caretaker, and heir to the movie queen. Following Davis’ death, she was charged with preserving the actress’ legacy, both by co-founding and serving on the board of directors of the Bette Davis Foundation and, more recently, publishing a memoir of her relationship with “Miss D.”

Miss D & Me: Life with the Invincible Bette Davis (Hachette, 2017) is the fulfillment of a promise Sermak made to her friend and sometime employer three decades ago.

Although she has worked with other noted, influential people throughout her career as a personal assistant, Sermak’s loyalties clearly remain with Davis. Every room of her West Los Angeles home contains some memento of her career with the actress — a career that might not have happened, she believes, had it not been for her USC Dornsife education.

“Fasten your seatbelts …”

The year was 1979. Sermak had graduated from USC with a bachelor’s degree in psychology two years prior. As she contemplated enrolling in graduate school, she accepted a job in Beverly Hills as a personal assistant to Princess Shams Pahlavi, eldest sister of the last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. When the princess relocated to Acapulco, Mexico, Sermak, a self-described surfer girl from San Bernardino, Calif., chose to stay behind and parlay her recent prestigious experience and education into a job interview with Davis.

“One of the reasons [Davis] hired me was because I was able to state on my résumé my extensive foreign travel — all of it through USC study abroad language programs — which made her think I was a sophisticated, multilingual young lady,” Sermak explains, running her fingers through her hair as she speaks.

She says that when she accepted the job at age 23, she had no idea she would learn a lifetime of lessons during the following 10 years.

“Miss D taught me everything,” Sermak says. She begins speaking at an increasingly rapid pace, clearly exuberant about the attention Davis devoted to her. “Yes, I learned a lot about film, but I learned more about life.”

Davis instructed her pupil on how to dress, how to eat, how to interact with people — both privately and publicly. When Davis thought Sermak’s handshake was lacking, she grabbed her hand and insisted that her employee of two days practice until it was perfect. She expected meticulous attention to detail from Sermak. She even suggested that Sermak alter the spelling of her given first name, Catherine.

“If you spell it K-A-T-H-R-Y-N, it’s more distinctive,” Davis counseled Sermak. “The way your parents chose to spell it is so much like everyone else in the world. I want to advise you that one of the big battles in life is to stand out from the crowd.”

As if directly taken out of a script for My Fair Lady – with Davis assuming the Henry Higgins role and Sermak as Eliza Doolittle – Davis gave her protégée lessons on how to walk and how to speak. Davis even fined Sermak a quarter each time she responded to a request with a “low-class ‘okay.’ ”

More than anything, though, Davis nurtured in Sermak an unwavering sense of devotion and perseverance.

“That first year was what I call boot camp — and it was very difficult because she kept testing me,” Sermak says. “A lot of people would have quit; a lot of people would have said, ‘I’ve had enough.’ But if you can persevere and go beyond, you succeed, and that’s basically what she taught me.”

Sermak retrieves her reading glasses for the third — perhaps fourth — time during our interview. She jokes about how she is always misplacing them as she scrutinizes the photograph I hand her.

In the photo, a woman with cascading chestnut tresses and luminous eyes stands next to Davis.

“I was never happy with how I looked back then,” Sermak says. “But now, I don’t know … ” She trails off for an instant as she reflects on the image. “I can’t imagine what I was thinking.”

The picture was captured in New York City in April 1989 — the last professional image of the screen icon.

This photo — along with the portrait in Sermak’s office with the watchful eyes — appears on the book jacket for Miss D & Me. Certainly, though, Sermak had seemingly unlimited options from which to choose: Her small but remarkably organized office contains thousands of photographs — both loose and in scrapbooks.

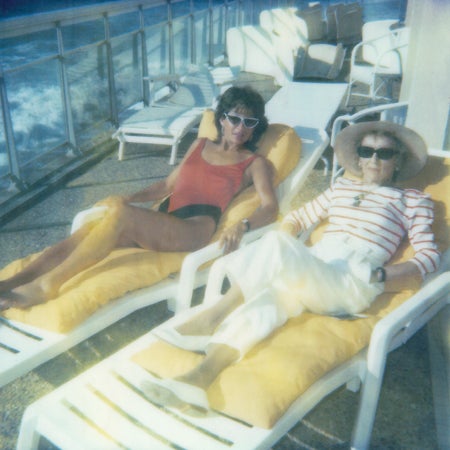

As we thumb through her photo albums, most of which are bursting at the seams with a mix of professional portraits and amateur shots, I’m in disbelief over the multitude of Polaroids she’s retained. Instant cameras, it turns out, were crucial to her ability to properly assist her employers throughout the years.

Whenever there was a personal appearance to be made, Sermak would use her camera to map the route to where Davis would make her entrance so that the aging star would be familiar with the location. I imagine how formidable Sermak would have been if she’d had an iPhone back then.

Mixed among the photos are other treasured possessions that guided Sermak as she wrote her book. She has saved numerous diaries and notebooks, yellowing newspaper clippings and birthday cards. There are audio recordings she and Davis made for one another over the years. Sermak started taping messages to her family and friends as a USC student studying in Spain because telephoning home was prohibitively expensive. The habit stuck.

Other one-of-a-kind items include a recently digitized video of an interview Sermak conducted with Davis toward the end of her life. Sermak hopes to one day edit the footage and have it appear on television. Those recordings lie on the bookshelf, directly beneath her prized antique dictionary, given to her by Davis, naturally.

Perhaps aided by the dictionary, Sermak jokes that she is seldom at a loss for words. So when we finally sit down in her home — a refuge she calls Casa Bella — to discuss her book, she begins to answer questions even before I’ve had a chance to ask them.

“Miss D. was furious — she loved her dining room table,” Sermak says as she sees me glimpse a rough knife carving in the table top. It reads, “Bette + Sherry 1945.” It was etched by Davis’ third husband, William Grant Sherry.

I notice the blue-and-white chaise in her living room. Sermak mentions that it was custom made for Davis back when she was working at Warner Bros. and simultaneously filming two movies at the studio.

Sermak details how Davis’ will bequeathed to her specific pieces of furniture — like the table and chaise — and how she left explicit instructions on how they should be cleaned and arranged. Think of it as interior decorating from beyond the grave.

“… a bumpy night”

“Miss Davis might have been 71, but let me tell you, … she could run circles around me, and I had a lot of energy,” says Sermak, describing her first years with the screen legend. “She could run circles around four people in their 20s.”

Davis and Sermak are not dissimilar in that regard. Nearly four decades since she went to work for Davis, Sermak still thrums with energy. She is the proverbial whirling dervish throughout our conversation, frequently ascending the stairs to her second floor office to retrieve more mementos of her career.

Sermak says that Davis only slowed down when she was felled by a stroke nine days after a mastectomy to treat her breast cancer in 1983. It was in Davis’ New York City hospital room that Sermak says the dynamic shifted between the duo.

“Those first five years, I was young, kind of weak,” Sermak explains. “She was the one who taught me how to walk and talk.” But following the stroke, they switched roles, with Sermak helping Davis relearn how to use her body.

“It’s almost like a life reversal,” Sermak says.

Sermak played an integral role in Davis’ recovery, overseeing every aspect of it, from diet to doctor’s appointments to making sure the star balanced rest and activity. Although it was months before Davis returned to her apartment in West Hollywood, and still more months before she ventured out in public, she eventually resurfaced with the help of Sermak — and the USC Trojan Marching Band.

Producing photos of Davis in a USC sweater with a color-coordinated hat, Sermak excitedly explains how she and Davis’ attorney arranged for the band to serenade the icon on her 76th birthday.

The entire neighborhood came out to see the band march down Havenhurst Drive in West Hollywood, Calif., to Davis’ residence at the landmark Colonial House building. Sermak and Davis looked on from their terrace. When the band finished playing, Davis blew the band members kisses from the balcony and despite having impaired mobility due to the stroke, asked Sermak to take her outside.

“She yelled down to the band from the fourth floor, ‘You stay right there. I’m coming down,’ ” says Sermak. “She went down and she shook everyone’s hands, thanking them. And it was the first time, really, that she came out [following the stroke].”

“We’re all busy little bees …”

As Davis recovered, Sermak went to France as the actress’ emissary, and wound up falling in love with a young lawyer. Sensing that her protégée needed to experience a life outside of Hollywood, Davis encouraged Sermak to leave her employ and move to Paris.

“Miss D said, ‘You’ve got to go. You’ve got to go see this man in his own country. I don’t think he’s right for you, but you need to get it out of your system.’ ”

“As it happened, she was right on both counts,” Sermak laughs.

While in France, Sermak worked for politician and journalist Pierre Salinger, but her loyalty to Davis never faltered. Whenever Davis needed anything, Sermak was promptly on a jet back to the United States. She helped Davis through a litany of health issues, assisted with the publication of Davis’ second autobiography, This ’n That (Putnam Publishing Group, 1987), and escorted the legend to important public engagements.

“… if you can persevere and go beyond, you succeed, and that’s basically what [Davis] taught me.”

However, in 1985, when Davis’ daughter Barbara Davis “B.D.” Hyman published a scathing tell-all book about her mother that deeply affected Davis, Sermak suggested Davis instead join her.

“That’s when I said she needed to come to France,” Sermak says. “I’d work on the [This ’n That] galleys and then we’d take this motor trip from Biarritz to Paris.”

It is about this trip abroad that Davis — still reeling from Hyman’s character assassination — insisted Sermak write a book. During their four-day excursion, Sermak unknowingly accepted the role of de facto daughter as their bond strengthened along the way to the City of Lights.

The duo sunned themselves by the pool at the historic Hôtel du Palais on the Bay of Biscay and shaded themselves under a café umbrella at a roadside restaurant. Sermak says Davis smiled at the fact that the umbrella was emblazoned with the Coca-Cola logo.

Sermak recalls Davis saying, “Ah, if Joan Crawford could see me. She’d be so angry,” alluding to the pair’s bitter rivalry and the late Crawford’s ownership stake in the rival soft drink Pepsi. (Some feuds simmer long after death.)

Davis donned a head-to-toe leather ensemble and checked out motorcycles in the Loire Valley, to the enthusiastic cheers of local onlookers. Sermak shares these and other Polaroid memories of their trip.

The jaunt was not all fun and games; it also allowed the two time to discuss hard subjects. Each shared what they wanted to happen upon their respective demises.

“Whichever of us dies first, the other will see to it that we look beautiful at the last,” Sermak recalls Davis saying. Many years before Davis had purchased her sarcophagus, which overlooks Warner Bros studios at the Forest Lawn Hollywood Hills cemetery; she would be buried beside her mother and sister Bobby. Davis had told Sermak she wanted the burial to take place at 4 a.m. when there would be less chance of paparazzi skulking around.

Another of the directives Davis made was for her own memorial: She forbade a hoard of celebrities offering insincere tributes.

“Miss D knew Hollywood,” Sermak says. “Somebody passes and all of a sudden they’re doing these memorials, and all these people come up and they start talking about how they were best friends. Davis told Sermak, ‘They’re all doing that because they need work, and they all want to be seen. And don’t you dare allow this to happen.’ ”

Sermak would find herself following through on her friend’s request four years later.

“Slow curtain, the end”

In the early fall of 1989, Davis lay dying in a hospital on the outskirts of Paris, her frail body ravaged by cancer. Only a select few — including Sermak — had been aware that Davis had been undergoing radiation treatment; no one expected her health to deteriorate so quickly.

“There was no way in the world we ever thought she was going to pass,” says Sermak as she holds up a faded Polaroid, shot in Spain, of Davis and herself — the last photo of Davis ever taken. “She looked the best I had ever seen her back then. It’s just like she blossomed.”

When the time came, Sermak volunteered to relay the grim prognosis to Davis that there was nothing more the doctors could do.

A physician later came to Davis’ room to check on her. Instead of pleading for some last reel miracle that might have appeared in one of her films, Davis’ celebrated eyes stoically fixed their gaze on the doctor.

“She apologized to him for having to put him in that situation — his hospital,” Sermak says. “She knew who she was. She knew the amount of press that was going to be there and how it was going to swarm. He was in tears. He had to leave the room.”

At the end, it was just Davis and Sermak; the actress wanted only the person who had become her closest friend and confidant to be with her when she died.

Sermak remembers placing farewell phone calls to family and friends for Davis, but the dying star did not want them to make the trip to France. Sermak says that Davis did not want their last memory of her to be, as Davis described it, “a bedraggled body and the look of death” reasoning that “they don’t see me every day like you do, Kath.”

“People often ask me if I miss her, and I say that I still feel her presence around me.”

Sermak took care of the funeral arrangements for the star. She selected a black evening dress and matching black fur hat created by designer and friend Patrick Kelly in which to bury Davis. Sermak made sure that Davis’ tomb at the cemetery was inscribed exactly as the actress explicitly requested: “She did it the hard way.”

Sermak offers that she does not profess to know what happens when someone dies, but she does feel that Davis’ spirit is still watching over her all these years later.

“People often ask me if I miss her, and I say that I still feel her presence around me.”

“A girl of so many rare qualities …”

After Davis’ death, Sermak continued her career, working for a who’s who of famous faces: astronaut Buzz Aldrin, actress Isabelle Adjani, music impresario Berry Gordy Jr., and Michael Gornall, the creative director of the Where’s Waldo television series.

But it is her relationship with Davis that continues to define her career. Up until now, with the exception of an appearance in the award-winning Spanish documentary El Último Adiós de Bette Davis, Sermak has been reluctant to discuss her work with Davis, despite numerous inquiries.

“Being a personal assistant and to have the respect that I do, you never gossip, you never say anything,” Sermak says. “I see behind a lot of doors, but it stays with me. The only time it didn’t is for this book because [Davis] told me, ‘You need to set the record straight. And, more importantly, it’s a great story and one day would make a great film.’ ”

Sermak felt unready to write the book, citing a need to reach a certain level of maturity before diving into the project. Immediately after Davis’ passing, in particular, Sermak says she was bombarded with requests to write a tell-all.

“That’s cashing in. They wanted scandal … and that is not who I am; that is not who Miss Davis was; that’s not how I was trained.”

As our interview concludes, Sermak offers me a red and yellow bloom — one of her USC roses. It’s a classy gesture — one seemingly plucked from Davis’ instruction manual.

I rush to my car, throw back the top, and scramble to find my long-forgotten Time Life Sounds of the Eighties CD.

Her hair is Harlow gold …

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2017-Winter 2018 issue >>