A comedian walks into a neuroscience lab

What exactly is going on in your brain when you come up with a joke? Well, that appears to depend on whether or not you tell jokes for a living.

Researchers in the Image Understanding Laboratory at USC Dornsife led by neuroscientist Irving Biederman studied professional improvisation comedians — many from the Los Angeles Groundlings comedy troupe — and amateur comedians in the act of coming up with a quip. They aimed to gain a better understanding of the neural correlates of humor creativity — that is, to see how the brain’s physiology changes as a person tries to be funny.

USC Dornsife doctoral student Ori Amir, now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Santa Barbara, led the study with Biederman, Harold Dornsife Chair in Neurosciences and professor of psychology and computer science. Their findings were published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Humor in particular

In the past, scientists have studied the neural correlates of creativity with tasks such as writing a poem, improvising jazz or drawing a picture, but humor offered Amir and Biederman a unique pathway to study how the brain processes creation.

“Humor is an outstanding testbed for studying creativity,” Biederman said. “It has a clear beginning, middle and end with a duration brief enough for neuroimaging. Also, the end product is easy to evaluate: Does it make you laugh? When someone creates an original composition or a poem, assessing the quality is not as clear cut.”

Irving Biederman, Harold Dornsife Chair in Neurosciences and professor of psychology and computer science, leads the Image Understanding Laboratory. Photo courtesy of Irving Biederman.

For their study, both professional and amateur improv comedians as well as a control group of non-comedians viewed New Yorker cartoons without words and were asked to come up with two captions for them — one that was funny and one that was mundane. Study participants were scanned by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machines to track their brain activity as they created the captions. All of the scan participants, as well as an outside panel of participants, rated each of the captions for their humor.

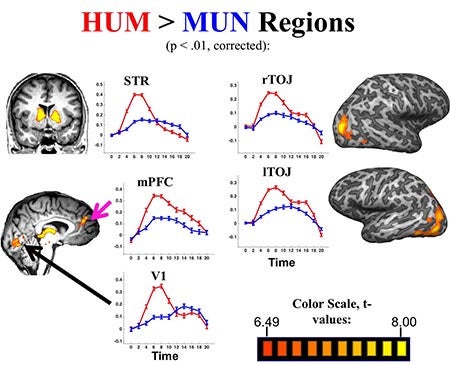

The results showed that two regions of the brain were activated when the participants came up with jokes — the medial prefrontal cortex and the temporal association regions. However, the regions activated were different depending on the person’s level of expertise.

“What we found is that the more experienced someone is at doing comedy, the more activation we saw in the temporal lobe,” Amir said. The temporal lobe receives sensory information and is the region of the brain key to comprehending speech and visual cognition. It’s also where abstract information, semantic information and remote associations meaningfully converge.

In contrast, the amateur comedians and non-comedians relied on their prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive functions like planning complex cognitive behavior and decision making.

“The amateurs and non-comedians engaged the prefrontal cortex, which is a more deliberate attempt at deriving a funny interpretation of a cartoon,” Biederman explained. “The professional improv comedians let their free associations give them solutions.”

To put it another way, “The more experience you have doing comedy, the less you need to engage in the top-down control, and the more you rely on your spontaneous associations,” Amir said.

The researchers also found that funniness ratings were higher for captions created while the participants had higher activity in the temporal regions of their brain during humor creation.

Researchers found that two regions of the brain were activated when study participants came up with jokes — the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the temporal association regions (TOJ). This figure shows the overall activation for generating humorous captions (HUM) and mundane captions (MUN). Figure courtesy Ori Amir and Irving Biederman.

Amir noted that across different studies that seek to understand the neural correlates of creativity in the brain, the medial prefrontal cortex is the one region that consistently is connected to creativity.

“The question is what does it do exactly? It seems like it’s not the source of creativity, but rather the cognitive control top-down director of the creative process. The creativity itself appears to occur elsewhere depending on the creative task,” he said.

Adding to the story

This study builds on the research from Biederman’s Image Understanding Laboratory, which studies the cortical basis of high-level visual recognition. The same temporal lobe regions that show high activation from humor are also activated by the aesthetic experience of appreciating a magnificent vista, for instance. Biederman’s research suggests that what may underlie both humor and aesthetics are that the cortical regions achieving vision have a high density of opioid activity which, more generally, may provide the neural basis for perceptual and cognitive pleasure.

Biederman notes that the activation, and hence the pleasure, is greatly reduced by the repetition of any experience. The thrill is gone the second time we hear the joke, read the book, or see a movie. Thus, the pleasure isn’t an end in and of itself, but it is what drives us to continually seek new and richly interpretable experiences. This then renders us, as Biederman has termed it, “infovores,”meaning humans are hard-wired to crave new information and experiences.