Let There Be Light

We all know what New Jersey is famous for. The birthplace of Ol’ Blue Eyes? Where Thomas Edison invented the light bulb? Heaven help us, Jersey Shore?

Fuggedaboutit!

The Garden State is home to one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of modern times. In 1949 — two years after their discovery in a Judaean desert cave — fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls found their way to New Jersey and eventually to an unassuming, red brick with white trim church in Teaneck.

For six decades, the fragments had been locked inside the church’s vault. St. Mark’s Syrian Orthodox Cathedral and Dead Sea Scrolls officials knew it was time to call in the heavy hitters to document the 2,000-year-old manuscript.

About 2,450 miles west, USC College’s Bruce Zuckerman got the call. A leading Dead Sea Scrolls scholar, Zuckerman was the first to record the New Jersey fragments dating around 100 B.C. using high-end digital technology. In August 2009, he and other West Semitic Research Project (WSRP) members brought their advanced imaging methods to the church and photographed the scrolls. Steven Fine of Yeshiva University in New York collaborated with WSRP, part of an ongoing partnership between USC and Yeshiva.

“Bruce Zuckerman’s team is the best and the most experienced in photographing ancient texts,” Weston Fields, executive director of the Dead Sea Scrolls Foundation, said from Jerusalem. “He’s definitely the first person anyone would think to call within Western scholarship.”

Inside his office at USC, Zuckerman, professor of religion and linguistics, pulled up some of the New Jersey Dead Sea Scrolls images on his computer screen. Written in carbon-based ink on parchment (possibly from a goat), many of the ancient Hebrew letters were indecipherable in conventional photos.

Founded in the early 1980s by Zuckerman and his brother, Kenneth, WSRP was the first to use polynomial texture mapping (PTM) to photograph the Dead Sea Scrolls, in addition to the standard practice of taking color and infrared images. The PTM technology uses the data from images taken at many different light angles to show the texture of the fragments’ surface.

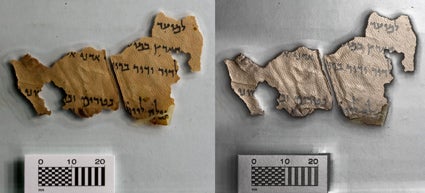

A fragment of the manuscript 1Q34bis Litugical Prayers, showing two images derived from an RTI (Reflectance Transformation Imaging) interactive image. The image on the left, in visible light, shows the textures of the skin on which the manuscript was written. The image on the right is in a mode called “specular enhancement,” which makes an object look like it was dipped in molten silver. One can now see both the skin texture and the depth of the ink on the surface of the skin. Image courtesy of the West Semitic Research Project.

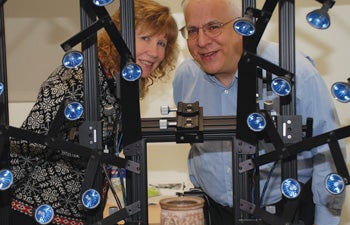

At his computer, Zuckerman examined a high-resolution image with Marilyn Lundberg, associate director of WSRP. Lundberg’s husband, John Melzian, along with Kenneth Zuckerman built the equipment enabling them to apply the cutting-edge photographic methods, originally developed by the Hewlett-Packard Company.

“Technology like this has never been used on the Dead Sea Scrolls until now,” Bruce Zuckerman said. “This New Jersey project was the first [in which] we were able to apply our method to such large fragments.”

Examining one fragment, part of a liturgical prayer, the pair spotted a tiny fleck on the first character in the word Adonai (Lord). They wondered whether the dot was parchment over the character, or a tiny hole scraped off the ink. Because the image had been photographed from every conceivable angle, the computer software program allowed them to see the fragment in many combinations of light and shadow. A click of the mouse on an image acted like a flashlight, revealing the tiniest of details.

Shining their virtual “flashlight” on the character, examining the texture of the skin, they concluded that a tiny bit of ink had flecked off the surface. At closer inspection, it also appeared the scribe had slightly messed up the ink stroke and made a correction.

Marilyn Lundberg and Bruce Zuckerman of the West Semitic Research Project (WSRP) stand behind the Tarantula, a contraption built by Kenneth Zuckerman in which dozens of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) go off during each shot of a revolving object. Photo credit Pamela J. Johnson.

“This technology gives us more information than we ever thought was possible,” Zuckerman said, adding that his students are also using the method to analyze the scrolls. “The information about the skin and the ink was unexpected. This gives us great hope for research of the future.”

Leta Hunt of USC Libraries and her engineers developed the viewer software, based on work by Hewlett-Packard and other universities. WSRP’s more than 35,000 images can be accessed through the InscriptiFact Database Application (InscriptiFact.com).

In February, Zuckerman traveled to Milwaukee, Wis., to deliver a lecture about the New Jersey Dead Sea Scrolls and WSRP’s advanced technology.

The scrolls are on display at the Milwaukee Public Museum through June 6. They were documented in connection with that event.

“Most people know the Dead Sea Scrolls are displayed at the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem,” Zuckerman said. “But I’ll bet most of the public has no idea that the 20th century’s greatest manuscript discovery is also in New Jersey.”

How the scrolls ended up in the Diner Capital of the World begins with a tale about three Bedouin shepherds searching the cliffs along the Dead Sea for a wayward goat in the spring of 1947. Inside a dark cave, one of them discovered several narrow jars with bowl-shaped lids. Hoping for gold, he found bundles wrapped in cloth, greenish with age. He told the others there was no treasure.

The young Bedouins had discovered the first seven manuscripts of the Dead Sea Scrolls, written about 100 years before the birth of Christ and 1,000 years older than the oldest-known Hebrew texts of the Bible. After hanging from a pole in a tent for awhile, the scrolls were sold for a small amount to a cobbler in Bethlehem.

The cobbler noticed that writing appeared on the skins when accidentally splashed with water. He took four of them to Mar Athanasius Yeshue Samuel. A native of Syria, Samuel was the bishop at St. Mark’s Monastery in Jerusalem and a collector of old manuscripts.

A bust of Mar Athanasius Yeshue Samuel, who brought the Dead Sea Scrolls fragments to the United States, and later became Archbishop of the Syrian Orthodox Church in the United States and Canada. Photo courtesy of the West Semitic Research Project.

“When Mar Samuel bought them, he thought they were interesting, but he didn’t know what they were,” Zuckerman said. “No one did.”

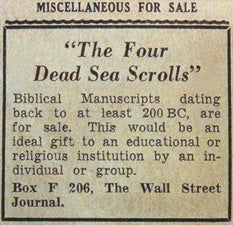

Samuel took them to scholars in Jerusalem who recognized their importance. He toured the United States with his scrolls trying to sell them, but couldn’t find a buyer so he placed an ad in The Wall Street Journal. Under miscellaneous for sale, the scrolls were promoted as “an ideal gift to an educational or religious institution.”

The 1954 advertisement in The Wall Street Journal offering Dead Sea Scrolls for sale. “When Mar Samuel bought them, he thought they were interesting, but he didn’t know what they were,” Zuckerman said, explaining why he put them up for sale. “No one did.” Photo courtesy of James E. Trever.

The scrolls sold for $250,000 to an intermediary acting on Israel’s behalf. But Samuel — who used the money to help victims of the war in Palestine and finance the growth of the Syrian Orthodox church in the U.S. — kept some of the fragments. He brought them to New Jersey when he became the U.S. archbishop of the church.

From 1949 to 1956, further searches yielded the remnants of about 900 scrolls in 11 Qumran caves. They included early copies of biblical books in Hebrew and Aramaic: hymns, prayers and other texts providing priceless insights into the culture that brought forth Rabbinic Judaism and Christianity.

After Samuel died in 1995 at 87, the fragments remained in the Syrian Orthodox archdiocese headquarters. Samuel himself might have been surprised at the technology being used to study these antiquities today.

Several offices in USC’s Ahmanson Center are filled with the futuristic-looking machinery Zuckerman’s team has created and uses to photograph ancient inscriptions. One contraption, dubbed the Twister, takes photos of an object perched on a turntable that revolves 360 degrees. Two other apparatuses nicknamed the Big Dome and Little Dome look like large black top hats adorned with red, white and blue wires. When artifacts are placed inside, photos are taken with light-emitting diodes (LEDs) staged in various angles.

Another room holds the Tarantula, a bigger, more powerful version of the domes with elements of the Twister. Lights are affixed throughout the seven-by-six foot gizmo. While lights turn on in succession, a camera shoots photos of an object balanced on a revolving turntable in the center.

“This is humanities enabled by science, by technology,” Zuckerman said. “As technology evolves, the line between humanities and science will continue to blur. It’s in this area especially that USC is leading the way.”

Visit the West Semitic Research Project online at usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp.

Read more articles from USC College Magazine’s Spring/Summer 2010 issue.