Southern California’s coast emerges as a toxic algae hot spot

A new, comprehensive survey led by USC Dornsife scientists shows the Southern California coast harbors some of the world’s highest concentrations of an algal toxin dangerous to wildlife and people who eat local seafood.

The research is the most thoroughgoing assessment yet and reveals the growing scale of the problem over the last 15 years.

The researchers say their findings can help protect human health and environment by improving methods to monitor and manage harmful algal blooms.

The findings are a “smoking gun” linking the neurotoxin domoic acid produced by some species of algae to deaths of marine birds and mammals, say the study’s main authors, David Caron, USC Associates Captain Allan Hancock Chair in Marine Science and professor of biological sciences, and postdoctoral researcher Jayme Smith.

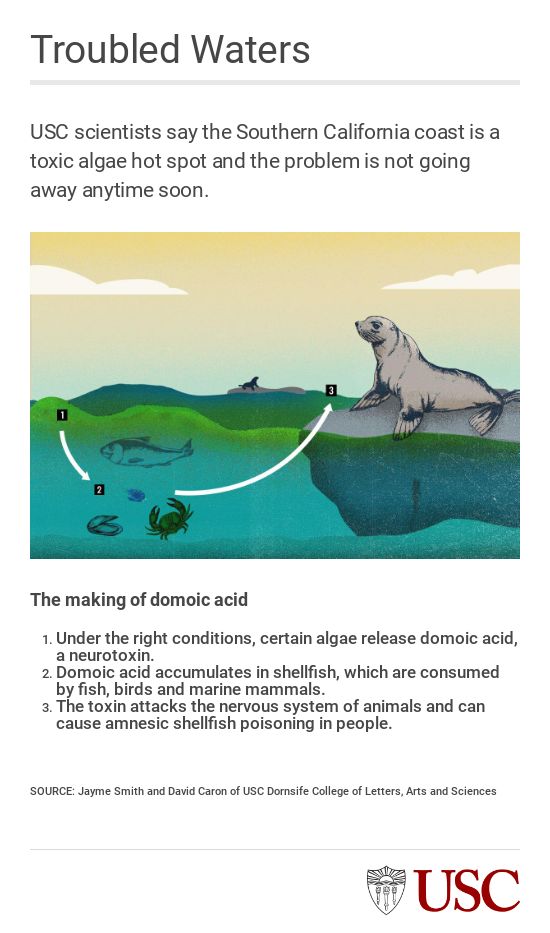

Illustration by Diana Molleda.

“We are seeing an increase in harmful algal blooms and an increase in severity,” said Caron, also a researcher with the USC Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies. “The Southern California coast really is a hot spot, and our study also shows that the concentrations of particulate domoic acid measured in the region are some of the highest — if not the highest — ever reported.”

The findings appear in the journal Harmful Algae.

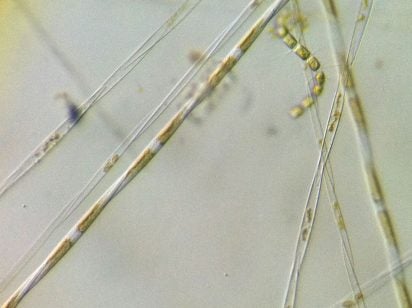

Domoic acid is produced by certain species of Pseudo-nitzschia, a needle-like group of diatoms. Diatoms are single-celled algae that have silica in their cell walls. Domoic acid can stain the ocean, a condition generically called “red tide,” although this particular type is brown.

The toxin accumulates in shellfish and moves up the food chain, where it attacks the nervous system of fish, birds, seals and sea lions. It can cause amnesic shellfish poisoning in humans. Symptoms include headaches, abdominal pain, cramping, nausea or vomiting. Severe symptoms include permanent short-term memory loss, seizures, coma or shock within 48 hours.

Although human fatalities are rare, the California Department of Public Health monitors coastal waters and shellfish for the toxin.

Sampling down the coast

Chains of Pseudo-nitzschia species cells collected during a toxigenic bloom. Image courtesy of Jayme Smith.

The research encompasses the years 2003–17 between Santa Barbara and the Mexico border, and includes new samples and tests collected over the past three years to supplement historical data.

The study suggests that while natural processes lead to the formation of blooms, they could be exacerbated by nutrients discharged from man-made sources, including runoff and sewage outfalls.

Among the key findings:

- Pseudo-nitzschia is the culprit behind domoic acid. It’s been present along the Southern California coast for decades, but its role in wildlife mortality is recent and increasing.

- The world’s highest domoic acid measurement in water occurred near San Pedro in March 2011. It was 52.3 micrograms per liter — about five times higher than a level of concern.

- Through the years, researchers found a strong correlation between domoic acid in the water and impaired marine wildlife on shore.

- Domoic acid is ever-present offshore, either in shellfish or the water. Some years it’s abundant, while other years it’s scarce.

- Conditions are worse in the spring, due to seasonal upwelling of nutrients that spur plankton growth. The toxin is less abundant in the summer and winter.

- Domoic acid in shellfish can occur at high concentrations off the coast of San Diego, Orange and Los Angeles counties, but it tends to be more prevalent in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties due to local environmental conditions.

- Man-made sources of nutrients contribute to algal blooms, but that doesn’t explain disparities in time and location of some of the domoic acid outbreaks. Other environmental factors are likely in play.

- The algae and its toxin diminish on the West Coast when water temperatures exceed 68 degrees Fahrenheit, apparently due to temperature sensitivity of the microorganisms.

Spreading up the coast

Also, a warming Pacific Ocean appears to be helping spread Pseudo-nitzschia species farther north. For example, harmful algal blooms have been widespread along the West Coast from Central California to Alaska in the past two years, according to the study.

The study brings together diverse data and observations that shed light on the environmental conditions that promote harmful algal blooms. Of note, an extreme drought across the U.S. Southwest between 2014 and 2016 resulted in very low concentrations of domoic acid off the Southern California coast. The findings imply a link between surface waters flowing to the ocean, or other drought-related conditions, and coastal algal blooms.

Those nuances and uncertainties need further exploration to explain the regional and year-to-year variations favoring toxic algae — key steps before more reliable health forecasts can occur, the USC Dornsife scientists say.

“Our findings summarize our present level of understanding with respect to this important animal and human health risk in Southern California waters and identify several avenues of research that might improve understanding, prediction and eventually prevention of these harmful events,” Smith said.

About the study

Study authors include Smith as lead and corresponding author, Caron as senior author, as well as Paige Connell, Erica L. Seubert, Avery O. Tatters and Alyssa G. Gellene of USC; Richard H. Evans of the Pacific Marine Mammal Center; Meredith D.A. Howard of the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project; Burton H. Jones of the Red Sea Research Center, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal, Saudi Arabia; Susan Kaveggia of the International Bird Rescue, Los Angeles; Lauren Palmer of the Marine Mammal Care Center, Los Angeles; Astrid Schnetzer of North Carolina State University; and Bridget N. Seegers of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the GESTAR/Universities Space Research Association.

The research was supported in part by the NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Sciences Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms Program (NA11NOS4780052, NA11NOS4780053, NA11NOS4780030), the Monitoring and Event Response for Harmful Algal Blooms Program (NA05NOS4781228, NA05NOS4781221, NA05NOS4781227 NA15NOS4780177, NA15NOS4780204) and the Harmful Algal Blooms Rapid Event Response Program (publication number ECO923, MER210 and ER25), the EPA [agreement number GAD# R83-1705], and grants and/or material support from the USC Sea Grant Program, the USC Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies, the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project, the Orange County Sanitation District, the California Department of Public Health, the Hyperion Treatment Plant of the city of Los Angeles and the Southern California Coastal Ocean Observing System.