A family’s old steamer trunk holds links to a dark period in the nation’s history

My maternal grandfather’s steamer trunk was gathering dust in my parents’ garage. With leather handles and metal clasps, it could be a set piece from the Titanic. Intrigued that a friend has just received a hope chest for her 16th birthday, I asked my mother if I could use the trunk in my bedroom. “You want that old thing?” she queried before agreeing. I hauled it upstairs, pleased to be repurposing a family heirloom.

Later, my mother casually mentioned that when she and her parents “left for camp” from Little Tokyo in Los Angeles, in May 1942, her father used this trunk to store some belongings that they had to leave behind. That was all she said. It would be years before I learned enough to understand its significance.

“Camp” was first the Santa Anita Assembly Center in Arcadia, California, then five months later, it was the Heart Mountain War Relocation Authority Center near Cody, Wyoming. These were two of the U.S. government detention facilities hastily constructed to imprison approximately 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

Pursuant to Executive Order 9066 issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942, soldiers with guns and bayonets forcibly removed Japanese Americans like my parents and grandparents from their homes, livelihoods and educations, on short notice. Anyone who shared ancestry with the Japanese enemy in the areas designated as West Coast military zones had to sell their businesses under duress or abandon them completely; they were fired from their jobs without cause and had to dispose of almost all of their household goods. Taking with them only what they could carry, they were transported under armed guard to these detention centers surrounded by barbed wire in desolate inland locations.

Without any evidence of disloyalty or charges brought against them, they were held captive for an undetermined amount of time simply because of their race.

My parents were among the two-thirds of those incarcerated known as Nisei, born as American citizens to Japanese immigrants. Their parents, called Issei, had experienced discrimination from the moment they had left Japan for America, their adopted country. In what the Issei had hoped would be a land of opportunity, they were targeted by those who feared Japan’s rise as a military power, by politicians with anti-immigrant sentiments, and by business leaders who characterized them as economic competitors. They were barred by federal law from becoming citizens, prevented from leasing or owning property in many Western states and were subjected to the prejudices against non-Whites and non-Christians common at the time.

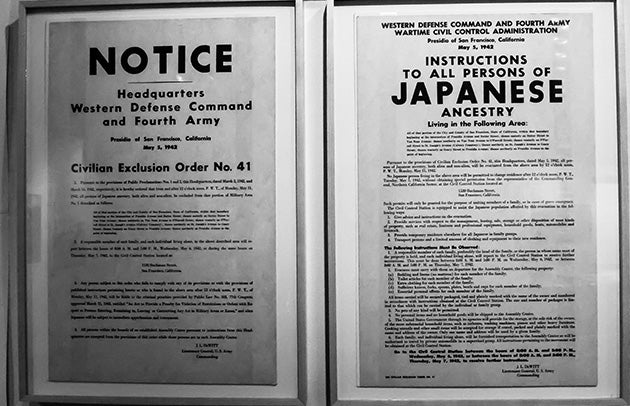

Executive Order 9066 sent thousands of Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens to prison camps during World War II. (Photo: Thad Zajdowicz.)

Powerless to push back against the frenzy of fear that swept the nation after Japan’s attack on Dec. 7, 1941, most felt they had no choice but to comply with the government’s detention orders. Upon their release after the war’s conclusion, they struggled to be viewed as loyal Americans as they sought to rebuild their lives destroyed by their abrupt and long-term incarceration.

One day while I was in college, my father told me about some of the challenges that he and his family faced when they returned to Orange County, California, following their release from the Poston, Arizona camp. Having lost everything, they were destitute but started over in vegetable farming. For the first time, I began to understand the enormity of the injustice that had befallen them.

In the mid-1970s, my father was among the incarcerated Nisei and politically engaged third-generation Sansei who sought to bring attention to this shocking episode in our nation’s history and to have the government acknowledge that its wartime actions were wrong. I joined my father and countless other volunteers across the country in support of legislative and judicial redress initiatives. With the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, surviving formerly incarcerated individuals received an apology for the government’s unjustified actions along with token payments as part of our country’s only large-scale reparations program to date.

Burdened by the shame of being treated as criminals, despite having done nothing wrong, and needing to put the hurtful past behind them to rebuild their lives in an anti-Japanese environment after the war, the Nisei kept their experiences to themselves for 40 years. Their opportunity to tell their stories in the early 1980s before a congressional commission was a cathartic experience for them and the entire Japanese American community.

Learning about the inequities suffered by other communities is necessary and important as our society grapples with issues of racial identity, immigration and citizenship. This is what has motivated me to teach an undergraduate course at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, sharing the relevance of the incarcerated individuals’ stories and why we should care about them today.

As part of my research, I examined the War Relocation Authority records on my incarcerated family members in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. In them, I found treasures of family history, such as a photo of my father at age 14. I was grieved to learn in their medical records of my grandparents’ poor health, their conditions exacerbated by the harsh camp environment. I was angered to read comments about their personalities included in sociological assessments that they most likely had no idea were being made. And I was amazed to find the receipt issued to my grandfather when he retrieved his trunk from storage upon his return to Los Angeles in February 1946.

His trunk now sits in my living room, an ever-present reminder of my family’s wartime subjugation. The story of my grandfather’s trunk is just one that could be told about the 120,000 incarcerated Japanese Americans, whose legacies have been cloaked by emotion and obscured by the passage of time. And yet, sometimes their messages are hiding in plain sight. As we observe the 80th anniversary of the issuance of Executive Order 9066, it’s appropriate that we hear, remember, and carry forward their stories as we consider what it means to be an American.

About the author

Susan H. Kamei is a lecturer in the Department of History at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. She is author of When Can We Go Back to America?: Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during World War II (Simon & Schuster, 2021).