The Books That Define California

Like the United States itself, California owes its existence to a book. In the case of the nation, it was Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which, appearing for the first time in January 1776, inspired Thomas Jefferson’s thinking as he composed the Declaration of Independence. California’s source text, on the other hand — the 1510 Spanish romance The Adventures of Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo — has the U.S. beat by well over two centuries. “Know ye,” de Montalvo writes, “that at the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California, very close to that part of the Terrestrial Paradise.” Twenty-three years later, when the Spanish mutineer Fortún Ximénez reached the southern tip of Baja, becoming the first European known to have landed on the peninsula, he chose to believe he had found this land.

In that sense, California has been a literary powerhouse all along.

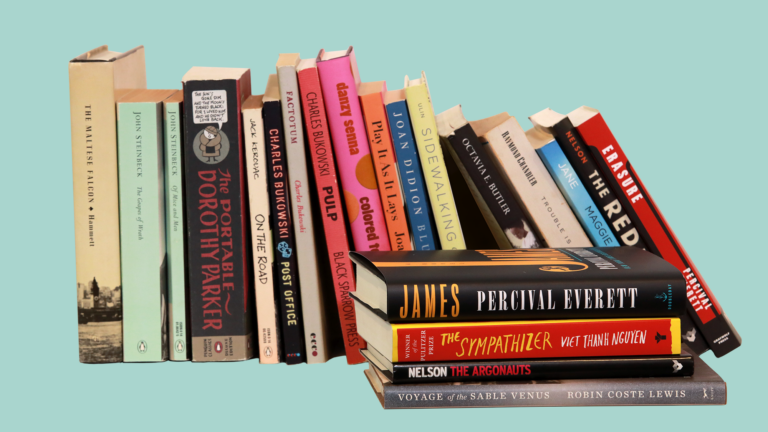

And yet, perhaps as compelling is Ximénez’s status as an outlaw and an exile, dual roles that have also helped define the literary identity of California. I think of Joan Didion and John Steinbeck, Octavia E. Butler and Wallace Stegner, all carving their own paths through the territory. I think of the noirists (James M. Cain, Dorothy B. Hughes, Eric Knight, Chester B. Himes) and the Beats (Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady, Lawrence Ferlinghetti); Hollywood (Gavin Lambert, Salka Viertel, Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker) and the literature of gay liberation (John Rechy, Lillian Faderman, Gil Cuadros, Terry Wolverton). What all of them have to tell us is that the art of the word here has long carried an edge of insurrection, of restlessness and movement, a desire to strike out and seek a newer world.

For contemporary writers in California, this has meant a constantly expanding heritage. We are in a never-ending state of becoming, in other words. Partly, this has to do with the dynamics of our elemental landscape, in which even the Earth itself might be said to be ongoingly in flux. Faced with such disruptions, we must check and recheck our certainties, our assumptions. We must be prepared to adjust. Do I need to say that this is a necessity for any artist? The act of writing, after all, is an act of figuring it out as one goes along. Not only that, but we remain unbound by conventional pieties or hierarchies. Why do so many California authors — among others, USC Dornsife’s Percival Everett, Maggie Nelson, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Robin Coste Lewis — consistently show up on award long and short lists? Because they are not afraid to take what they need from a variety of forms, blurring boundaries between word and image, subverting genre, mixing and matching with an exhilaration born of true experimentation, which is, of course, what art requires.

Such blurring, to me, has long been a defining factor in the literature of California. “There are no vital and significant forms of art; there is only art, and precious little of that,” Raymond Chandler insisted in his 1944 essay “The Simple Art of Murder.” What he meant is that it doesn’t matter what form a piece of writing takes, just the artistry it contains. In that sense, California writers benefit by their distance — both aesthetic and geographic — from the literary centers of the east. Even now, when, with the rise of independent publishing, the hegemony of New York as a culture center has been (thankfully) disrupted, there is great value for the artist in working a bit out of the spotlight, in having the chance to experiment and try new strategies with neither expectation nor attention. It is, in fact, a necessity.

“Know ye that at the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California, very close to that part of the Terrestrial Paradise.” Rodríguez de Montalvo was not working from experience when he wrote that, but it resonates all the same. As to why, it’s because he was working as a California writer works, following his intuition, weaving together the strands of myth and narrative — in other words, and as every one of us does, making it up as he goes along.

_______

David L. Ulin is professor of the practice of English at USC Dornsife and editor of Air/Light, USC’s online literary journal. He is the author or editor of a dozen books including Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay, and Writing Los Angeles: A Literary Anthology, which won a California Book Award. The former book editor and book critic of the Los Angeles Times, he has written for The Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, Virginia Quarterly Review, The Paris Review, and The New York Times.