About the Undergraduate Program

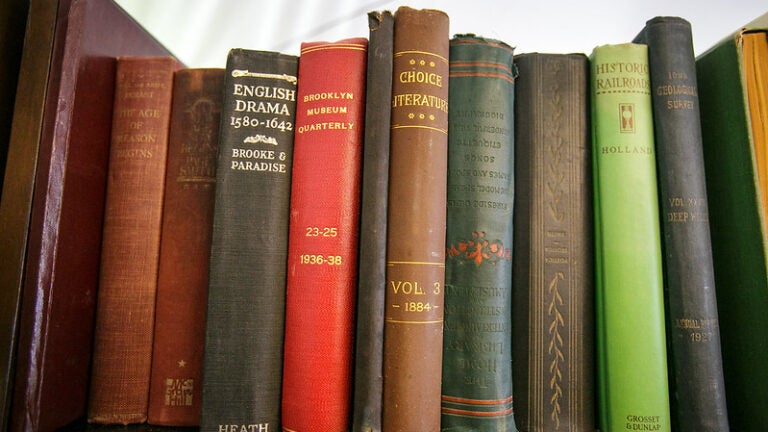

We offer a broad range of courses in English, American and Anglophone literature of all periods and genres, but also in related areas such as creative and expository writing, literature and visual arts, ethnic literature and cultural studies, the history of the English language and of literary criticism, and literary and cultural theory.

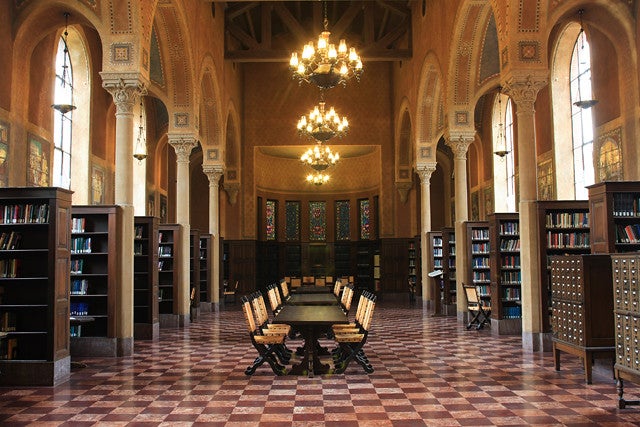

Class sizes are kept at 19 to enable full discussion (12 in creative writing workshops). Instructors assign extensive reading and writing in order to help students become perceptive readers, critical thinkers and strong writers. Our literature and creative writing courses reinforce one another, and we counsel students to take classes in both areas.

We have nearly 40 full-time faculty and they are always available for advisement. Many share appointments in other departments and can help guide you beyond our department and beyond USC.

We believe in the value of study abroad and will help you to find programs that are right for you. Students who wish to go beyond our regular courses of study can apply for our Honors Program, and we honor excellent work in English with our extensive program of prizes and awards. We run innovative Maymester programs in literature and creative writing, and our undergraduate associations provide ways for students to share interests in small settings.

Learning objectives for the English major

A student with a major in English should graduate with an appreciation for

- the relations between representation and the human soul

- the relations between words and ideas

- the social utility of a sophisticated understanding of discourse

Assessment of objectives

Assessment of these three learning objectives reflects the fact that literature is a way of knowing, rather than a gathering of information or theories. We prefer the intense engagement of seminars and small classes to the inevitable asymmetry of large lectures. Students cannot hide; they are under the immediate supervision of faculty. We monitor student progress through close encounter, oral presentation, and the continual exchange of written work both with faculty and among peers (particularly in creative writing workshops). We experiment with lectures where appropriate, but in general find that for freshmen and sophomores small classes provide the best introduction to rigorous argument and the testing of understandings in language. We have explored capstone classes, but have found that the small classes currently required of all our juniors and seniors serve the same purpose more efficiently and with greater variety. As our department and university move toward greater interdisciplinary work, the prospect of a coherent capstone administered by any one department seems less likely.

Every fall we offer two seminars in literary theory that are open to any senior, and required of any senior hoping to advance to our Senior Honors Thesis in the spring. These seminars are based on current research interests by selected faculty and actively demonstrate methodologies that students will need for their own advanced work. Recent seminars have researched the relations between Renaissance England and Islam, while scheduled seminars include experimentation in narrative forms in early twentieth-century novels. Our commitment to assessment through seminars and small classes requires a faculty consensus about criteria and standards. Our Honors Program provides one way to forge consensus. Students are admitted only upon application and must submit papers graded in earlier courses that demonstrate likelihood of being able to succeed in a sustained research project. These submissions are evaluated by a faculty committee whose membership rotates. Our theses must be supervised and read by at least two faculty members; all faculty must participate, all decisions are reached in concert, and all students present their work publicly before faculty and peers. Assessment in creative writing also requires consensus about criteria; admission to advanced seminar is by application and submission of a portfolio evaluated by our senior writers. Creative projects submitted for the Honors Program require both a creative component and a critical literary component, with separate faculty supervising each component. Throughout the year we canvass our faculty for likely candidates for the Honors Program; this helps us identify both capable students and those who need more attention.

We have a number of competitive undergraduate prizes awarded within the department that help to forge consensus about criteria and standards. The William James prize has two separate competitions—one for the best critical essay by a freshman or sophomore, and another competition for juniors and seniors. All faculty take turns as readers and all decisions are reached through discussion. The Edward W. Moses prize for creative writing likewise is read and judged by all creative writing faculty in turns. We continually reassess our procedures and criteria for all prizes.

Introductory courses at the freshman and sophomore level likewise are governed by communal faculty understandings of goals and assessment. We use roundtable discussions for courses with several sections, sharing syllabi and encouraging exchanges about expectations, while avoiding rigidity and sameness. We monitor syllabi across the department, looking for parity in workloads and modes of evaluation. Our junior faculty each have a mentoring team of three senior faculty, and their classroom teaching is observed each year. The number of college and university teaching awards garnered by our faculty, combined with our awards in general education and in student mentoring, argue for the strong standards and common sense of purpose shared by our colleagues.

The resurgence of our self-governing undergraduate student association (Sigma Tau Delta) is evidence that faculty have conveyed a sense of appreciation for our discipline. Not all assessment comes from faculty. Students increasingly have taken their coursework directly into the community, designing and executing projects in local schools. Our creative writing students actively engage with neighborhood public schools, and at the end of January they filled one of the large lecture halls on campus for a public reading of the children’s own poetry. Our students in literature are prominent in the university’s Joint Education Project for outreach to the USC community, and a number of our classes incorporate JEP activities. We are approached repeatedly by organizations and companies seeking our students for internships ranging from public relations and advertising to film and publishing. These and other forms of community assessment complement our internal academic assessment.

We have an excellent record of placement for our students, but we are leery about this as an index of assessment since students come to us with their own learning objectives, and in the real world we must balance their objectives with ours. In recent years our graduates have been placed in every major law school in the entire country, and particularly in the northeast. Our literature students have been accepted at Oxford, Yale, Michigan, Harvard, Chicago, Stanford, and a host of other principal programs. Recent creative writers have gone on to the best MFA programs in the country: Iowa, Otis, Sarah Lawrence, Columbia, Cornell, American University, Virginia, Wyoming, Las Vegas, NYU and UCI. We must not take this achievement as the sole measure of our success, but it does provide another fiduciary to validate our internal assessment.

Our goal cannot be mere replication of the professoriate or service provision to the professions, and we do not articulate either of these among our learning objectives. Flexibility of mind, facility with expression, and a sense of continuity with the past are ways of thinking and engagement that may not develop fully until years after graduation. We believe immediate assessment must be coupled with long-term assessment of fifteen years or more, when we canvass our graduates and ask whether the English Department prepared them for the lives they now live. Here is a sampling from the class of 1992: a filmmaker and film editor in Mexico City, a principal technical writer at Oracle, an insurance and retirement planner, a vice president of new product development at Scholastic, the registrar at the Colorado School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, a head of marketing at Intel, the owner of Gyro Digital in Connecticut, the owner of a luxury real estate firm in Manhattan Beach, a graphic designer in Los Angeles, the managing editor of the Huntington Library Press.

Learning objectives for the Narrative Studies major

To study narrative is to study the control of implication, to recognize that what isn’t said – or seen, or heard – is as important as what is said and how it is said. These aspects shift according to culture, time, and audience, with shared understandings, perspectives, materials, media, and procedures. No single discipline embraces all of these aspects to the exclusion of other disciplines. Conversely, disparate explorations need to be brought together in a way that makes personal sense to each individual student. Our studies in narrative are based in the humanities, coordinate with practice in the arts and media, and culminate in an individual project that will be unique to each student.

Contact Details

USC Department of English

3501 Trousdale Parkway

Taper Hall of Humanities 404

Los Angeles, CA 90089-0354