Entering The Digital Age: Transcribing Handwritten Excavation Notes For Modern Usage

By Ariel Gilmore

Being transported back in time feels like something only possible in science fiction novels, but the Tell al-Judaidah project transports users to a spot on the Mediterranean Coast, the Amuq Plain in modern-day Turkey, to experience the Stone, Bronze, and Digital Ages.

USC undergraduate archaeology student Ivana Karastoeva worked with the Tell al-Judaidah project online, which is a fully digital publication of a major excavation that was shut down by World War II, and she experimented with spatial representations in the online OCHRE Database supported by the University of Chicago. Her goal? To contribute new data for an interactive map of a dig site on a high mound overlooking a fertile agricultural plain through which rivers wind and which saw Hittite kings giving way to Assyrian overlords, and then to the Persians, Greeks, Romans, and Christians.

The original dig at this high mound created by thousands of years of people living at this site took place in 1932 under the guidance of researchers from the University of Chicago. They were searching for sites relevant to the Bible. One of them, an archaeologist named Robert Braidwood, documented his fascinating finds with a pencil and a small notebook nearly a century ago. Karastoeva gained access to these records and transcribed them from fading handwritten materials that have narrowly survived many decades and transferred these notes into locations in a spatial database.

Karastoeva’s research aimed to create an attribution system that allows locational data to be attached to images and drawings in order to support an online interactive interface. This contributes to one of the project’s goals: an online map that users can move through to examine the site’s rich stratigraphy that began in the Neolithic (6000 BC) and extended through the Bronze and Iron Ages, the Roman, Greek, Persian, Christian, and beyond. Today, people still bring their herds to camp at this ancient place.

Though Karastoeva is still in the early stages of developing an interactive map, her work so far has brought a pressing matter to light.

According to Karastoeva “Finding findspots of ancient objects unearthed in 1935 has been a difficult task, to say the least. I had to navigate through a great deal of information and use some trial and error to find evidence to support the spot where I was placing the artifact spatially. However, this careful research yields an important outcome: enabling accurate documentation and public accessibility while supporting continued scholarly dialogue.”

The plot that Karastoeva has been working on for her research is plot E9 which is located on the edge of the site, overlooking a nice spring, a critical water source. Her primary responsibilities for this plot include pinpointing findspots for artifacts that lack clear spatial coordinates. She then assigns corresponding pins in the OCHRE database to link an artifact to a specific location on her map.

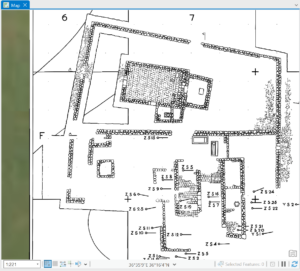

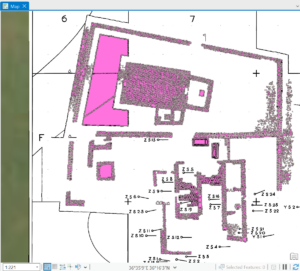

The first step of this process is uploading scans from plot E9 into the geographic information system software program, ESRI’s ArcGIS so that Karastoeva can georeference them to create coordinates in the real world. Next, Karastoeva traced out structural remains to have them be separate features from the original image, and finally, that is turned into a vector layer to be used in the final map render.

Transforming excavation notes that were scribbled onto pieces of paper moments before the world would be shaken up by the global turmoil of World War II highlights the challenge of creating accurate documentation on busy, hot days amid pressing world events. But, we see these archaeologists leaving a trail, breadcrumbs for people to follow in the future when they investigate this ancient place. Karastoeva is working to bring a long, rich history into the digital age by preserving and recovering spatial information and making it accessible. Her work on the interactive aspects can allow people to clearly see what was done by enterprising archaeologists a century ago. She’s creating a kind of time machine to glimpse lives that were lived at this site for thousands of years!