Turning air into fuel: USC chemists convert carbon dioxide into methanol

They’re making fuel from thin air at the USC Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute.

For the first time, researchers there have directly converted carbon dioxide from the air into methanol at relatively low temperatures.

The work, led by USC Dornsife researchers G.K. Surya Prakash and George Olah, is part of a broader effort to stabilize the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by using renewable energy to transform the greenhouse gas into its combustible cousin.

“We need to learn to manage carbon. That is the future,” said Prakash, professor of chemistry and director of the USC Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute.

The researchers bubbled air through an aqueous solution of pentaethylenehexamine (or PEHA), adding a catalyst to encourage hydrogen to latch onto the carbon dioxide under pressure. They then heated the solution, converting 79 percent of the carbon dioxide into methanol. Though mixed with water, the resulting methanol can be easily distilled, Prakash said.

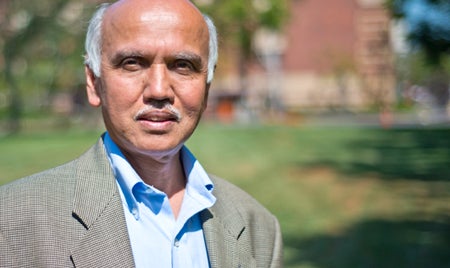

G.K. Surya Prakash, professor of chemistry and director of the USC Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute.

Methanol is a clean-burning fuel for internal combustion engines, a fuel for fuel cells and a raw material used to produce many petrochemical products.

Replacing petroleum fuels one day

Prakash and Nobel Laureate Olah, Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Distinguished Professor of Organic Chemistry, hope to refine the process to the point that it could be scaled up for industrial use, though that may be five to 10 years away.

“Of course it won’t compete with oil today, at around $30 per barrel,” Prakash said. “But right now we burn fossilized sunshine. We will run out of oil and gas, but the sun will be there for another five billion years. So we need to be better at taking advantage of it as a resource.”

Despite its substantial impact on the environment, the actual concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is relatively small — roughly 400 parts per million, or 0.04 percent of the total volume, according to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. (For a comparison, there’s more than 23 times as much of the noble gas Argon in the atmosphere — which still makes up less than 1 percent of the total volume.)

Keeping it cool(er)

Previous efforts have required a slower multistage process with the use of high temperatures and high concentrations of carbon dioxide, meaning that renewable energy sources would not be able to efficiently power the process, as Olah and Prakash hope.

The new system operates at around 125 to 165 degrees Celsius (257 to 359 degrees Fahrenheit), minimizing the decomposition of the catalyst — which occurs at 155 degrees Celsius (311 degrees Fahrenheit). It also uses a homogeneous catalyst, making it a quicker, “one-pot” process. In a lab, the researchers demonstrated that they were able to run the process five times with only minimal loss of the effectiveness of the catalyst.

Olah and Prakash collaborated with graduate student Jotheeswari Kothandaraman and senior research associates Alain Goeppert and Miklos Czaun of USC Dornsife. The research, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society on Dec. 29, was supported by the USC Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute.