Still Life

Packed neatly in brown paper and carefully tied with string, hundreds of bundles of music sat forgotten on the shelves of a linen closet in the Los Angeles home of Judith Anne Still’s mother.

One spring day in 1980, Judith Anne discovered them.

“I felt a wave of grief wash over me,” she said. “My father had died two years earlier and now it was as if his music — his entire reason for living — had died with him.

“My father’s work was forgotten and nobody cared about it anymore. It was like a second death.”

William Grant Still had been considered “the dean of African American classical composers.”

“What a tragedy, nobody is standing up for this man,” Judith Anne thought as she studied the rows and rows of bundles. Then and there, she resolved to devote her own life to rescuing her father’s memory from obscurity.

“I had to do it,” she said. “There was no one else.”

Born in Woodville, Miss., in 1895, William Grant Still blazed a trail through the American musical landscape for half a century, composing more than 150 classical works, including symphonies, ballets and operas.

His distinguished career included stints as the recording director of the first African American owned record label, Black Swan, and as an arranger of film and popular music. A recipient of two Guggenheim fellowships, he chalked up an impressive series of firsts.

In 1931, his Afro-American Symphony was the first symphony composed by an African American to be played for an American audience by a major symphony orchestra. His work leading the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl in 1936 marked the first time an African American conducted a major orchestra. In 1949, Still became the first African American to have an opera staged by a leading company when the New York City Opera performed Troubled Island, his opera featuring a libretto by Harlem Renaissance poet and writer Langston Hughes. He was also the first black composer to have an opera screened on national American television. In 1955, when he led The New Orleans Philharmonic, he was the first African American to conduct a major orchestra in the Deep South.

William Grant Still, his wife, Verna Arvey, their two children, Judith Anne (left) and Duncan, and their beloved dog Shep, gather around the radio at their home near USC to listen to a broadcast of the composer’s music on Sept. 14, 1944.

But despite his outstanding talent and prodigious output, Still struggled with financial hardship for most of his career. This was compounded latterly by a noticeable decline in attention to his music following the production of Troubled Island, which he and his family attributed to racial discrimination.

Still was a man of faith. His greatest desire was that his music serve to create racial harmony.

“My father had so much hope during the great success of the Afro-American Symphony that his music would really make a difference and bring people together,” Judith Anne said. “But after Troubled Island everything seemed to go in the other direction.”

“He believed in the rectitude of the creative impulse. So although very disappointed that he wasn’t going to see it in his lifetime, he believed that one day his music would foster racial harmony.”

Following a series of heart attacks and strokes, William Grant Still died in 1978 at age 83, in his adopted city of Los Angeles, largely forgotten and deeply saddened that he had failed to achieve this mission during his lifetime. At the time of his death, interest in his work had dwindled to such a degree that not a single viable recording of his compositions existed and only a handful of performances of his music, including radio broadcasts, were being given on average each year.

Determined to resurrect her father’s legacy, in 1980 Judith Anne founded William Grant Still Music, now based in Flagstaff, Ariz., where she now lives.

“This is going to be easy,” Judith Anne thought at the start. “But I’d write to conductors and they wouldn’t answer, or I’d write to record companies and they’d tell me black classical music doesn’t sell.”

Judith Anne realized that to have any success rekindling her father’s memory in the face of such widespread indifference, she would have to do everything herself. She used an old air check radio recording of Lenox Avenue, her father’s ballet set in Harlem, to create an LP. She then persuaded the North Arkansas Symphony Orchestra to record the first performance of her father’s Third Symphony. She was also instrumental in getting her mother’s biography of her father, In One Lifetime (The University of Arkansas Press, 1984), published.

She wrote to music professors across the country to market these products.

“They were successful, so we took that money and then mortgaged everything: the house, the furniture.” She paused before humorously adding for emphasis, “the pets — even the goldfish.”

“With the money, we made more books and recordings, and sent out records and CDs to radio stations.”

From these humble beginnings, Judith Anne’s determination to revive her father’s music has grown into a flourishing business that has brought many of his greatest works to new generations of music lovers. William Grant Still’s work is now performed or broadcast on the radio more than 40,000 times a year. Numerous recordings of his compositions and a wide selection of books and articles that tell his inspiring life story — many written or edited by Judith Anne — are readily available online and in libraries. Recently, she had built a new climate controlled building to safely house her father’s vast archive.

Born in 1942, Judith Anne grew up a few blocks from USC in the family’s modest Spanish-style stucco home on Cimarron Street, in what at the time was a segregated neighborhood. Her mother, Verna Arvey, Still’s second wife, was of Russian-Jewish descent and a successful music journalist, librettist and concert pianist. Circumventing California laws banning interracial marriage, they wed in Mexico.

Judith Anne’s childhood memories are happy ones. Her parents did not have much money, but they enjoyed a wealth of warmth and love, and a wide circle of friends, many of them well-known artists who frequently visited their home.

However, while her parents could relax with their trusted friends, she remembers they erected a 5-foot-high chain link fence around the house for protection. Racism during that period was rife, even in supposedly liberal Los Angeles, and interracial couples were targets. Despite these concerns, her parents created a secure and nurturing environment for her and her brother Duncan, and the house on Cimarron Street was filled with laughter and music.

“The sounds of slowly evolving chords and harmonies coming from the workroom piano were as familiar to us as the smells of the evening honeysuckle or of the sheets fresh from the clothesline,” Judith Anne wrote in her collection of essays about her father, A Voice High-Sounding (The Master-Player Library, 1990).

Her father was also a talented carpenter who made furniture for their home and intricate jigsaw puzzles and toys for his children. He was an enthusiastic gardener whose “victory garden” during World War II produced an abundance of vegetables, which he shared with friends and neighbors.

Judith Anne Still with her father, William Grant Still, a few years before his death in 1978.

“My father was a wonderful mixture of Gandhi, Einstein and your kindergarten teacher,” Judith Anne said affectionately. “He was a sweetie, very spiritual in nature and not at all an egotistical person.”

He enjoyed sharing his love of music with his children, creating homemade kazoos out of combs and tissue paper to amuse them. However, painful memories of his own mother’s insistence that he study medicine rather than music — which she believed was not a respectable career for an educated person of color — impelled him to never force his children to play an instrument.

Thus, when Judith Anne’s mother pushed her to learn the piano, the celebrated composer intervened, saying, “Leave her alone, she’s going to be a writer.”

And she did, winning several awards for her writing, including an Independent Publisher Book Award in 2008. Still won a full scholarship offered by USC to academically gifted students of color and majored in English in USC Dornsife.

“USC was thinking out of the box in offering these wonderful opportunities,” she said, referring to some of the nation’s first minority programs.

The Still family already had close connections with USC. Still had given talks at the university, where he had many friends. Students and faculty were familiar with his music from the concerts he gave at nearby Exposition Park.

While attending USC Dornsife, Judith Anne was active in honor societies Phi Kappa Phi and Phi Beta Kappa. She also fondly remembers evenings spent playing the card game bid whist and reciting poetry with friends at the Trojan Grill, then a popular eatery in the basement of the student union.

Judith Anne met her future husband, Larry Allyn Headlee ’65 at USC, while he was studying for his master’s in marine geology in USC Dornsife. The couple married in 1962 and had four children, the second of whom, Lisa, was born seven days after Judith Anne graduated magna cum laude.

Although her years at USC coincided with a period of major political upheaval, including the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Judith Anne’s devotion to her children and her studies kept her preoccupied. Despite the demands of her growing family, she continued her studies and graduated from Cal State Fullerton with a master’s degree in English in 1968.

After graduating, her husband worked on a mini-submarine for a private company, General Oceanographics. In 1969, Headlee’s mini-submarine rescued crewmembers of another mini-submarine trapped on the ocean floor at a depth of 432 feet. Judith Anne’s marriage was tragically cut short when Headlee drowned saving a fellow crewmember while attempting to raise a sunken pleasure cruiser off the coast of Catalina Island on Sept. 21, 1970.

“USC helped us through in the lean years after my husband died,” she said. “The USC Symphony played my father’s piece Rhapsody, dedicated to the memory of my husband, and my whole family attended.”

Both she and her father maintained lifelong ties with USC, which never forgot William Grant Still’s outstanding contribution to classical music. The university awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1975. The composer’s final public appearance before his death was at a USC-hosted tribute dinner to commemorate his 80th birthday. Then-Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley was among the many guests and the eminent composer and conductor Howard Hanson flew out from New York to lead the tributes.

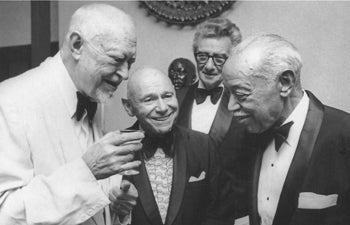

The last public appearance of William Grant Still (far right) at USC on May 24, 1975. The event was a tribute to Still. Dr. Howard Hanson (left) delivered the keynote address. Dean of the USC Thornton School of Music, Howard Rarig, is just left of Still.

When Still died three years later and his family struggled to pay the funeral expenses, USC stepped in and organized a memorial concert.

USC has played a continuing role in her family’s life, Judith Anne said.

“Sometimes it seems as if everything radiates from there,” she said. “A couple of years ago USC had a concert of my father’s work and our old neighbors from Cimarron Street came to hear it.”

Five generations of the Still family have forged and perpetuated the legacy of William Grant. The composer acquired his deep love of music from his grandmother, Anne Fambro, a former slave who taught him the great African American spirituals, then called Negro spirituals, and from his stepfather, Charles Shepperson, who brought home a Victrola gramophone and introduced him to the operas of Verdi and Puccini. His father, William Grant Still Sr., who died when the younger Still was a baby, routinely traveled 75 miles from Woodville, Miss., to Baton Rouge, La., to learn the coronet and later started a uniformed band in Woodville. His mother, Carrie Still Shepperson, an English teacher, pianist, choral director and strict disciplinarian, was the dominant force in his early life, giving him the determination to succeed against all odds.

Now his daughter’s devotion to his memory has ensured that his musical legacy will not be forgotten. Judith Anne’s daughter, Lisa Headlee, who is working on a book of photographs of her grandfather, is poised to receive the baton from her mother and carry it forward.

“My father’s motto was ‘We all rise together or we don’t rise at all,’ ” Still said. “My cherished hope is that my father’s story will one day be brought to an even wider audience through a feature film.

“I want to accomplish my father’s longed-for dream of using his music to bring racial harmony and understanding to our country.”

Read more articles from the Fall 2012/Winter 2013 issue of USC Dornsife Magazine