Riley Gold, Cinema and Media Studies

January 24, 2025

In August 2024, I visited the Honeywell, Inc., Corporate Records at the Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) in St. Paul, Minnesota (Fig. 1). My interest in Honeywell stems from research into cybernetics and histories of environmental regulation. Thermostats are often invoked as simple illustrations of automatic feedback control, and Honeywell traces its corporate history to the first automatic thermostat for buildings patented in 1886. [1]

More than one year ago, while perusing the MNHS website, I noticed that the Honeywell collection listed boxes of films and videos. Much of this audiovisual material was not yet digitized. In correspondence with archivists at the MNHS (especially Colin Dunn—thank you!), I ordered digital copies of motion pictures spanning approximately 1918 to 1988. Together, the films and videos tell a story about Honeywell: from its humble beginnings in the thermostatic regulation of homes and factories to its evolution into a multinational conglomerate involved in aerospace, computing, industrial automation, munitions, and numerous other fields. World War II marks a critical turning point when the company began to produce more diverse control apparatuses including an electronic autopilot system that required training films for pilots, mechanics, and bombardiers. Altogether, the motion pictures enable a genealogical inquiry into the promise and aesthetics of “automatic control” in twentieth-century America.

The Honeywell, Inc., Corporate Records include marketing materials, newsletters and journals, company histories, patent files, photographs, and other documents. To visit the records in person was the logical next step in my research on the Honeywell motion pictures. My first day in St. Paul, however, the MNHS was closed. Instead, I visited the Charles Babbage Institute Archives (CBIA) at the University of Minnesota. The CBIA contains records from the 1971 Honeywell vs. Sperry Rand patent infringement case, including a midcentury (undated) Remington Rand film on the history of computing. Ultimately, none of the materials were particularly relevant to my project; it was nevertheless an informative sidequest.

At the MNHS, I was fortunate to locate key contextual information about the motion pictures. There were certainly disappointments: I could not find any references to The Heart of the Heating Plant, a silent film from approximately 1918 advertising Minneapolis Heat Regulator Company products. But I tracked down a comprehensive list of the C-1 Autopilot films produced by Walt Disney Studios with Honeywell for the US Army Air Forces, as well as a document providing background information on the films and the broader educational program run by the Air Forces Training Command (Fig. 2). The latter document from 1945 even references public screenings of the films that address the theory of the autopilot system. “Those released here cover only basic principles,” its authors write. “Over-simplified to the skilled technician, they nevertheless break down electronics into layman’s terms and it is hoped that they will help the average person obtain a better understanding of the science which is doing so much in war and which is expected to find so many uses in the peace that will follow.”

The report thus intimates Honeywell’s postwar expansion and the proliferation of control technologies into millions of people’s everyday environments in the United States. A triumphant, unified image of automatic control appears decades later in the 1988 video Honeywell: Helping You Control Your World, where humans move from one Honeywell-regulated environment to another (home, car, office, factory, aircraft, laboratory, even space station). The video opens with a close up shot of the company’s iconic, round thermostat (Fig. 3).

Reading through contemporaneous company newsletters at the MNHS, it became apparent that this renewed emphasis on control was part of a rebranding effort to distance the corporation from previous associations with automation, computing, and defense. The thermostat, a consumer-facing interface for environmental management, was an accessible representation of a control logic which Honeywell proposed could scale to systems of varying sizes and degrees of complexity. As I continue to engage with these materials, I am thinking about the aesthetic work that sought to unify diverse control technologies into a single concept and expectation for stability and comfort. In turn, my aim is to also question what histories are occluded by the insistence on the thermostat and the promise of automatically controlled environments.

Thank you to the Visual Studies Research Institute and the Center for Science, Technology, and Public Life at the University of Southern California for generously funding this research.

Footnote

[1] My research is made possible thanks to interdisciplinary scholarship on digital control and/or environmental regulation by, especially, Seb Franklin, Yuriko Furuhata, Thomas J. Misa, Michael Osman, and Nicole Starosielski.

Wakae Nakane, Cinema and Media Studies

December 6, 2024

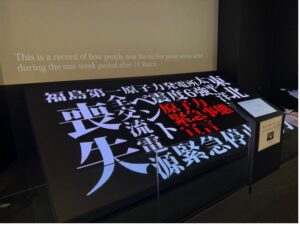

This summer, with funding from the Visual Studies Graduate Certificate, I conducted field and archival research in the Tohoku area of Japan. My research aims to explore the interconnected relationships between the new media ecology of the 21st century and the representation of catastrophe, focusing specifically on first-person records and memories related to the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Since the nature of the radioactive disaster in Fukushima affected a larger area even beyond the legally mandated evacuation zones, the archives and sites I sought to consult span vast areas of the Tohoku region. As a result, I traveled across Fukushima, Yamagata, and Iwate to fulfill my research objectives.

One of the first insights I gained from my research trip was the significant gap between the government/corporate-led official history and the micro-level, personal accounts of the experiences. I first visited the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum, which is run by the Fukushima Prefectural government and located less than 3 miles from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. The archival materials they store range from family albums washed away by the tsunami, to the hazmat suit worn by workers at TEPCO (Tokyo Electric Power Company), a model of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and testimonial footage of survivors recounting their experiences of the nuclear disaster. While these materials convey a complex process of remembering the traumatic memories of the nuclear catastrophe, the narrative is framed as a teleological story of recovery. One of their self-promoted principles is “the faster path to recovery.” For example, although the “storytelling” section of the museum dedicates ample space to survivor testimonies, the footage lacks any criticism of the government or TEPCO. This is largely because the archive has created a manual instructing narrators not to criticize any particular party or to control their emotions while speaking. This archival facility exemplifies how a catastrophic event is incorporated into the national public narrative of tragedy and recovery.

In contrast to the linear and teleological narrative presented by the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum, archives such as the 311 Documentary Film Archive at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival Archive and the Center for Remembering 3.11 at Sendai Mediatheque have sought to address the difficulties of representing a catastrophic event while also serving as community spaces to share memories of the disaster. The 311 Documentary Film Archive, located in the city of Yamagata—home to the biannual Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival—stores 116 documentaries. As my research specifically explores the role of subjective expressions of the nuclear disaster, I viewed documentary films made by both professionals and amateurs that use first-person, diaristic documentation, including Fukushima Berlin (Hikaru Suzuki, 2014), A Story of Grown-ups: Taro from the Land of Tsunamis (Atsushi Uenaka, 2014), MIHOCAMERA 18 (Miho Horiie, 2012), and Shocked Self and the Nuke: From the Perspective of a Tokyo Dweller (Emi Ishimoto, 2013). Although the documentaries in the archive vary in terms of technical sophistication, they share a common visual vocabulary centered around the evasiveness of their common subject, nuclear catastrophe, and their shared wrestling with the peculiarities of consumer video. As a result, we can say that first-person expression has emerged as a prominent stylistic tendency among documentarians.

At the Center for Remembering 3.11, I first noted the specific spatial arrangement of the center, which includes ample open space with tables, audio-visual rooms, and a recording studio designed to facilitate participatory activities. The Center exemplifies the networked capacity of public culture and the participatory aspects of archival practices, as archival scholars Jeannette A. Bastian and Andrew Flinn describe as “community archives” (Bastian and Flinn, 2020). The Center functions as a multimedia hub that encourages collaboration between various sectors—citizens, experts (filmmakers, scholars, writers, etc.), and staff—who work together to record, edit, and disseminate materials through written texts, films, photos, and audio recordings. The materials housed at the Center vary, but a significant portion consists of audiovisual materials that include interviews and recordings from the affected areas. In terms of materials related to the Fukushima nuclear accident, there is a greater emphasis on audio materials in which people express concerns about the accident, radiation, and the prospects for community reconstruction. These audio materials reflect the challenges involved in representing Fukushima and the issue of radiation.

In addition to these archives storing audiovisual materials, a particularly memorable aspect of my trip was visiting ruins affected by the earthquake. The ruins, such as Ukedo Elementary School in Fukushima and Sendai Aramaki Elementary School, have been preserved for visitors. The area surrounding Ukedo Elementary School is designated as a “hazardous area” by the government, and it is no longer habitable. However, it was striking to see how not only the tsunami-damaged school structure is preserved, but how it also serves as an archive of regional history, displaying materials that document the history of the local community. Overall, my research trip to the Tohoku region was incredibly fruitful, not only in terms of accessing audiovisual materials but also in observing how specific locations and the communities themselves serve as dynamic sites for preserving and documenting memories of the catastrophe.

Jessica Hanson, Art History

November 8, 2024

VSRI Summer Grant funding over the past several years has been essential to the inception and development of my dissertation, “Sports, Illustrated: The Making of the Global Image in Sports Photography, 1900-1974.” Working on an international project, I have realized since becoming ABD just how much my (largely VSRI-funded) ability to travel and do exploratory research during my years of coursework exposed me to materials and prepared me to conduct research in institutions abroad.

As a brief introduction to my project, it offers a history of the relation between media history, sports history and internationalism. Although art historians have examined sports photography in the form of case studies in national contexts, my dissertation aims to be the first art historical work to emphasize how both photography and sports culture have a unique capability of bringing people together across national and political lines. This project reads aesthetics into athletics and aims to provide a critical framework for this very ubiquitous—but deeply undertheorized—category of imagery in modernity. Moving chronologically from 1900 to 1974, each of my dissertation chapters tracks the significance of sports photography to one of five globalizing projects: anthropological documentation, world’s fairs and related traveling exhibitions, the Olympics, illustrated magazines and live television. Tracing the history of physical culture centered in Europe and the United States, I historicize sports imagery in relation to wider sociopolitical tensions between nationalism, internationalism and universalism as forms of global culture.

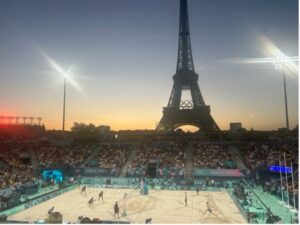

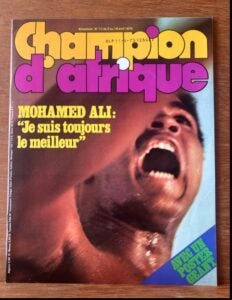

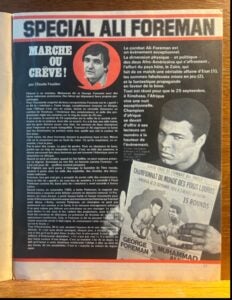

Although I have been living in Paris and conducting most of my archival research here around town, my VSRI funding enabled me to visit the Musée National du Sport in Nice for a week over the summer. Due to the structure of my dissertation and where my necessary archives are located, I have been focusing my research thus far on my bookend chapters: the first focused on early 20th-century anthropological documentation and the fifth focused on live television, particularly coverage of the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” Muhammad Ali boxing match. The Musée National du Sport is a rich resource for both, with huge holdings of sports-focused periodicals and ephemera contemporary to the time periods in focus. A kind archivist named Léna (who I met during a previous research trip) pointed me to a few publications that might be helpful, including the American boxing publication The Ring and the pan-African sports magazine Champion d’Afrique. The latter has been immensely helpful in my understanding the significance of the mediatization of the 1974 boxing match both locally in Kinshasa (where the event was held) and to the international African community.

In addition to such special-interest publications, I also took the opportunity in the archives to look through issues of earlier, more general sports publications such as Le Sport universel illustré and La Vie au grand air. Although these publications exist in Paris at the BnF, I’m always refused when I request them because they’re digitized. I find it much more helpful (and much faster) when I’m going through many issues of a publication to view them in person, so I was thankful they allowed me to view them in Nice.

I have always found the research tips and tricks from other VSRI graduate students to be extremely helpful, so I’ll share a few of my own from my time in France:

Tip #1: Plan well in advance. Most archives (and even many museums) I’ve visited in France are closed at least one day of the week, and it’s not always Sunday. The Musée National du Sport, for example, is closed on Tuesdays, and many museums are either closed or only open for half-days on Mondays. France also continues to observe a handful of Catholic holidays for which public institutions (including most museums and libraries) are closed. Also, many archives and libraries are closed for a few weeks (and sometimes even a whole month!) over the summer, usually around July to August. If you only have a week or two for your trip, be sure to double-check the dates and times your intended archive is open and set realistic goals with these in mind.

Tip #2: Be aware of (academic) events around town. Google in advance, but also keep a look out for fliers and posters! France hosts a “festival de l’histoire de l’art” (Art History festival) every year at the Fontainebleau castle, with dozens of talks, panels, screenings and other interesting events focused on a yearly theme and invited country. 2024’s invited country was Mexico and the theme was sports (!!), so it was clearly very relevant to my work. Each day of the conference I picked one or two speakers to try to meet after their talks, and I ended up connecting with multiple scholars and archivists who have been helpful with my project.

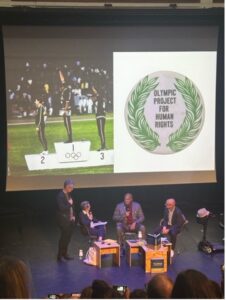

I later attended a series of lectures on Olympics history organized in conjunction with an Olympics exhibition at Palais de la Porte Dorée. I discovered this event after viewing the show; often in Europe, exhibitions will end with a sort of “credits” wall that lists the organizers and curators as well as associated programming. The event was particularly special because it ended with a roundtable with Tommie Smith, the gold medalist in the iconic 1968 Olympics Black power salute photograph (which is a key image to my dissertation).

Tip #3: Use an online whiteboard. I use the website Miro because it’s quite intuitive—and to be honest it’s the only one I’ve tried—but I believe Canva has a similar functionality as well. It’s helpful to be able to combine text and images in one place, and to be able to scroll in and out to visualize different parts of the project. Prior to Miro (and sometimes still) I organize images through Google Slides, which is a bit more orderly but makes it difficult to envisage the images in dialogue with one another. I’ve found Miro helpful in brainstorming and collecting raw images and information in a format conducive to the later writing process. Regardless of how you organize/visualize your images, make sure they are saved in multiple places!

Jarred B. Hamilton, Religion

October 25, 2024

This past June, with generous funding from the VSGC, I had the opportunity to visit the Royal Library in Brussels and the Ruusbroec Institute (RI) at the University of Antwerp. The Royal Library has one of the most extensive collections of medieval manuscripts and the Ruusbroec Institute (Fig. 1) is a leading research center for the study of Christian spirituality and holds over 40,000 devotional prints, 500 manuscripts, and some relic objects for study. I also visited surrounding towns, including Bruges, Mechelen, Leuven, and Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

Some brief background of my research and the context of my visit: my research interests have coalesced around medieval women’s mystical texts, the physical places and cities these women lived, and the visual reception of their theologies in later centuries. Specifically, I am interested in the lives and devotion of semi-religious women, ‘beguines,’ who emerged in the Low Countries (modern day Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxemburg) during the late 12th century. They are understood as semi-religious because these women did not belong to a convent or forgo chastity (some were married). Nonetheless, they led devout lives of voluntarily poverty, cared for the sick, and purported divine or ecstatic experiences that led to an emergence of hagiographical literature detailing their miracles, practice of extreme asceticism, and commitment to manual labor. Beguines lived on the edge of religious orthodoxy – facing tension with Catholic Church officials – but they also lived on the edge physically sometimes outside the walls of the city in complexes called beguinages (Fig. 2 & 3). Beguinages were mini towns walled off from the public and they often included a hospital, a chapel, and women’s living quarters. Unlike convents, women could come and go as they pleased.

Prior to my visit, I was in touch with Professor John Arblaster who serves as the Director of the Ruusbroec Institute, and he offered to show me around a few of the beguinages as well as help oversee some of my exploratory research at the Institute. Pro-tip: get in touch with someone affiliated with the archive center you are visiting to get the “insider” knowledge prior to your visit.

My exploratory visit involved two inquiries. First, I wanted to explore the physical layout of the beguinages as well as the art and architecture of the chapel within the complexes. Although theological texts written by beguines or their hagiographers rarely contain information about their living quarters, I wanted to find connections between their theologies and their lived experience within these ‘mini-towns’ and the wider cityscape. This inquiry proved to be somewhat difficult to explore because some of the beguinages (Bruges and Leuven) have been converted into private residences. Luckily, many of the beginuages had gift shops that possessed many books (in Dutch) that detailed their founding, the political relationship with the adjoining city, and well-known beguine residents. Sometimes, the gift shops hold the archive materials you think belong at the research center.

My second inquiry involved examining the visual reception of these women in later centuries. The sixteenth and seventeenth century saw a rise of devotional prints circulating in the Low Countries. These prints not only help fashion small cults devoted to medieval beguines but also allowed many devotees to possess portable artifacts with them so an attention to pious living remained present. Many of the prints are not available online and thus, required visiting in person. Of the abundant amount, many of the devotional prints held by the RI featured Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the disciples – particularly St. John – very few of them feature beguines. The beguine most featured is 13th century saint, Lutgardis of Aywières (Fig. 4) and there are many twentieth-century prints and fewer early modern items – a fact I was not anticipating. However, I was able to look more closely at some of the small relics (Fig. 5) the RI has in their collection as well as compile an extensive bibliography of titles in French and Dutch that I am slowly working through.

Being in such a small country as Belgium, I was also able to visit many art museums and cathedrals across the region which spurred new research ideas. Additionally, I was privileged to connect with one of the special collections’ researchers at the Royal Library as well as a few of the professors affiliated with the RI and U of Antwerp. Lastly, there are pros and cons to visiting a university center during the summer. So, while the research visit ended up taking new directions than I had initially not anticipated, the visit proved to be incredibly valuable for future fellowship applications and my looming dissertation project. I remain extremely grateful to the VSGC for catalyzing my very first abroad research trip.

Tania Sarfraz, Cinema and Media Studies

October 18, 2024

The VSGC Summer Grant funded my visit to the B.F. Skinner archive in Massachusetts, housed in the Harvard University Archives (there’s institutional continuity for you: Skinner was a student and then a professor at Harvard, and now his textual remains are interred on the same premises.) Skinner forms a tentacle of my dissertation project, feeling around the places where behaviorism, that supervalent force of twentieth-century American psychology, might have shaped contemporaneous film and media theory. My project queries a broad turn to the senses in contemporary media aesthetics and philosophies of technology, with a particular emphasis on discourses of error/failure, and the consequences these turns have had for the field’s conceptions of ‘world’ (variously as globe, planet, or milieu.) Behaviorism is a speculative addition to the array of objects within it, motived by the surprising absence of consideration that has been given to its towering status at a time when film theory (in the U.S., that was primarily cognitivist film theory) was also flourishing.

Skinner’s radical behaviorism can be captured in the polemical idea that the aim of psychology ought to be the prediction and control of the organism (not, say, the furnishing of an account of its actions, not a depth psychology of the subject.) This is a severe, one might be tempted to say inhuman, view of subjectivity and its sciences, and his view of environments and their relations with organisms were equally severe. The reflex, the mediating process between organism and environment, was rigorously (and counter-intuitively) defined without reference to physiology, purely as a behavioral correlation, as if the organism had as little physiological interiority as psychological. It’s remarkable to think that Skinner was writing at around the same time as continental theorists (e.g. Canguilhem’s account of the reflex), yet Skinner’s thought seems to have faded from intellectual histories (all the more so within cinema and media studies.)

It was in the archives, going through early drafts of Skinner’s PhD dissertation, that I discovered the vigorous resistance his concept of the reflex had received from his advisor, who thought it a vast overreach that tried to intervene in the history of philosophy (why argue with Descartes if you’re just a psychologist, opined the advisor.) Also of interest was a brief line in one of Skinner’s private correspondences on the errors of Norbert Wiener and cybernetics. The material I looked at was, on the whole, varied and dense (ranging from correspondence with fellow psychologists, to manuscript drafts, to press coverage) and I’ll be spending the next few months sorting and culling, nearing a decision on whether or not to keep this tentacle or chop it off. Regardless of that decision, this was an informative trip not merely in terms of content but also in terms of showing me some of the ways that archival research can work, what it might offer, and how it can or cannot articulate with scholarly modes that otherwise lean towards close textual reading.

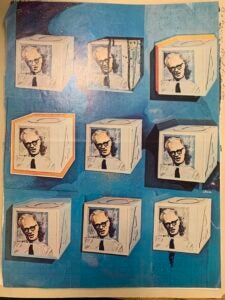

In closing, here’s Skinner from the November 1972 issue of Psychology Today, all boxed up in a design that minimally recalls one of his more iconic inventions, the Skinner Box:

Claire Carcara, Art History

October 4, 2024

This summer, with funding from the Visual Studies Research Institute, I traveled to both Marfa, TX and New York, NY to conduct exploratory research on the work of contemporary artist Donald Judd (1928 – 1994). Although vast amounts of scholarship have been written on Judd’s artistic practice, comparatively little scholarly attention has been paid to the larger Gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”) of Marfa, a small West-Texan town in which Judd renovated a number of buildings to both house and create art, as well as to live. Even less attention has been paid to Judd’s various projects that move outside his so-called artistic practice: his design work (especially that beyond furniture), which included textiles, tableware, and jewelry; his work at Eichholteren (Judd’s home and studio in Küssnacht am Rigi, Switzerland); the artist’s curatorial interventions in public spaces, most notably his floor design for the Lange Voorhout Palace (The Hague, Netherlands) and a curated room for the Österreichisches Museum für Angewandte Kunst (Vienna, Austria). My primary goal for this summer research was to locate materials that would contextualize Judd’s work within these various spaces and across the “scale” of his various, seemingly disparate yet interconnected practices. This summer research also enabled me to explore material that dovetails with my broader interests in art made under para-institutional conditions (art that is not necessarily anti-institutional, but rather made alongside art-world institutions), as well as artists which blur traditional distinctions, such as that between “high” and “low” culture, between artist and author, or that between “art” and “design.”

My first stop was Marfa: a small yet art-riddled town in the high desert of West Texas, approximately three hours from the nearest airport in El Paso [fig. 1]. Dissatisfied with the art world’s many failings—not the least of which was their disrespect for postwar artists and the artists’ work, as well as various museums’ penchant for bad architecture—Judd had leveraged Marfa’s once-cheap real estate (which included the former Fort D.A. Russell, a vast complex with buildings large enough to properly house Judd’s ambitious projects, and which would become the site of the Chinati Foundation) to generate ideal spaces for the permanent installation of contemporary art. These spaces, however distinct Judd aimed to keep their designated function, were in fact innovatively multipurpose—the boundaries that designated a space as for exhibiting, working, or living ranged from porous to non-existent. With my time in Marfa, I not only spent three days in the Judd Foundation’s archive consulting as much material as I could productively see, but I also toured some of Judd’s sites, including the Chinati Foundation. While the Block is only a block or two off Marfa’s main drag, Chinati is just outside of town, providing ample space for Judd’s large-scale installations, such as his 15 untitled works in concrete [fig. 2]. My visit also coincided with the monthly opening of Judd’s library to visitors; I brought my journal and spent some time reflecting while I sat in the Block’s tranquil courtyard (it was tolerable in the shade, but my late-June visit meant that the temperature inside the library was near-sweltering) [fig. 3].

As I had known in advance, Judd’s archive presented a challenge that I had not previously encountered: I could not photograph the material. Whereas my typical archival strategy involved photographing all the material I was looking at—thereby capturing much more than I could actually read or transcribe, to be processed later—this archive necessitated a different approach. Before traveling, I created a spreadsheet that would help me organize what I had looked at, and included columns to track the archive’s organizational system (series, folder, etc.) as well as descriptions of each item, its contents, and the date it was produced [fig. 4]. My days in the archive centered around strategic transcription, and I focused on accumulating information rather than answering my questions: I wanted to ensure that I would have any and all information I would need for future writing. Further, I made a note to purposefully treat the archival materials in terms of their visuality and their materiality—my notes included remarks on the kinds of paper used, their sizes, and their treatment (if a particular piece of paper had been folded, for example), as well as remarks on the typeface or handwriting. I thank Professor Luke Fidler for his extraordinarily helpful advice on working in archives with photographic restrictions, as his advice directly informed this approach.

My trip to New York later in the summer then served to round out my knowledge of Judd’s spaces. Although Judd’s home at 101 Spring Street has been heavily photographed, I had never been in person—an experience I would now say is integral to my understanding of the space. Like the sites in Marfa, Spring Street also has a strict policy on no photography. In lieu of photographs, I took notes on those elements that are missing from discrete photographs of the building’s interior, no matter how comprehensive their coverage. I noted things like sightlines—what was visible from each corner of the room—as well as the various views through the windows. My trip (and tour) bolstered my understanding of Judd’s specificity in regards to how he articulated spatial relationships, and provided the necessary three-dimensional context to a worked space I had only seen in photographs. Above all else, the trip once again underscored the importance of viewing artworks in person rather than via reproduction; at Spring Street, I gained a new appreciation for the scale at which Judd was working, and the architectural features that he was working both with and against—such as the height of each floor’s ceiling. Outside of the single cast-iron building that Judd once called home, I also used my time in New York to visit other SoHo sites, including Walter De Maria’s Broken Kilometer and Earth Room, both of which are only a handful of blocks from 101 Spring Street. Above all else, my trips this summer underscored the idea that no work of art—particularly when it is a five-story tall cast-iron building in the middle of Manhattan or a series of renovated buildings across the dusty, desert town of Marfa—exists in isolation. Judd’s sites are as porous as his practice.

Nisarg Patel [નિસર્ગ પટેલ], Comparative Studies in Literature and Culture

September 27, 2024

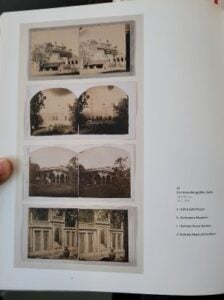

VSRI― which has continued to support me in ways that are too many to enlist here― generously funded my 2024 summer archival trip to Germany. The purpose of my trip to Germany was two-fold: I was to present a paper on contemporary Indian literature at a conference organized by Universität Tübingen [expenses funded by Excellence Strategy of German Federal Gov.] and then, by taking one of those famous German Trains [Deutsch Bahn], I was to go to Berlin to conduct preliminary archival research in the collection of photography housed in the Berlin Museums, particularly Museum für Fotografie [Image 1] and Museum für Asiatische Kunst [expenses funded by VSRI]. This would be the first time that I was to conduct archival research that was related to a proposed chapter of my dissertation (and I was pleasantly surprised by the things I found in the collection), and it was also the first time that I was in “Europe” (and, well, it was a pretty ambivalent experience; more about this later).

I wish I could share those rare stereoscopes here [stereoscopes that I have not seen even in big museums]. However, and this is the tricky thing with the personal collection, Dr. Bautze didn’t want me to take pictures of them. I wonder if my being a (mere-) Ph.D student and not someone more ‘established’ impacted Dr. Bautze’s decision. But then, as I was leaving his 1st-floor apartment where he and his wife have collected a lifetime of documents, sketches, maps, paintings, and photographs of Asia (both South and South East Asia), the last thing that Dr. Bautze told me was, “don’t hesitate to reach out and ask….for anything.” Generosity of strangers.

However, Germany was not all generous and pleasant, and the unpleasantness started before I even stepped into the country. At the Schengen Visa office, Alba Safullima, an employee of the private company that handles the visa process (and not a German citizen, from what I can tell), kept asking me to prove that I indeed was a PhD student at USC. She kept asking for documents not mentioned on the German Gov. Visa website (e.g., my enrollment letter to USC). When I pointed out that the checklist of required documents didn’t mention the documents she was demanding from me, she said that she had the authority not to take my application and that she could end the interview right there and then. She made me write a letter explaining why my itinerary had two empty days with no hotel booking, even after I explained to her that I was traveling during those nights [Image 4]. At the end of my “interview,” she told me that my visa application would possibly be rejected because of insufficient documentation. I would also see her making a remark on the document that she was to fill, and which I am assuming the German consulate reads, with the statement that “the person was in-cooperative” ― as if I was in custody and was being interrogated, good old police language!

Talking about police, I learned that walking as a Brown/Indian person in German airports is not something you would like to undergo. I was stopped by a police officer for ‘random’ checks thrice (after I cleared customs, mind you) and had to show them that I indeed have a visa to be in glorious Europe. All three times, they would ask for my visa, my boarding pass, where I was going, how long I planned to be in Europe, what I was doing there, etc. They would look at me with a blank stare when I told them that I was a researcher. I wish the saga of humiliation ended here, but, well, it didn’t. The peak was when Frau Muller at a sandwich shop wouldn’t simply look at me, even when it was just me in the shop, and I had said “Hallo” thrice to get her attention [I was served a sandwich by her co-worker]. This, too, was Germany―hostile and racist.

Kate Tomashevskaya, Slavic Languages and Literatures

September 20, 2024

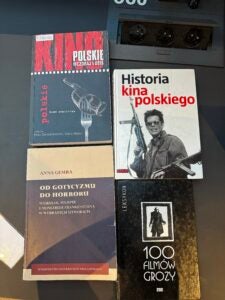

This summer, supported by the Visual Studies Graduate Certificate program, I conducted research in Warsaw and Berlin for my dissertation on the emergence of horror cinema in Poland and the former Soviet Union. The horror genre in Eastern Europe has long been considered underdeveloped due to its authoritarian past. Communist governments sought to limit the influence of horror films, viewing them as products of Western capitalist culture that spread decadent values and aesthetics. The genre’s focus on fear, supernatural elements, and often pessimistic perspectives did not align with the ideology of building a socialist society. However, countries of the Eastern Bloc produced a number of exceptional horror films that remain largely unexamined due to their limited availability. Many such films were restricted to national archives and private collections. Some were available on the internet; however, their quality was very poor. In recent years, the situation has slowly been changing, and films are becoming more accessible, although most are still available only in their original languages, which makes them inaccessible to many researchers. Therefore, very little has been written on this topic, and most of the existing literature is not available in English. My research aimed to change that by examining the early stages of the horror genre’s development in this region from the 1980s through the 1990s, revealing similarities and differences in styles and themes, and highlighting an alternative trajectory in the development of horror in Eastern Europe, distinct from that of the West.

To explore Polish cinema archives and encompass materials, including posters, photos, scripts ranks, and academic publications related to Polish horror films, I went to Warsaw for three weeks to work in Biblioteka Narodowa, Warsaw Public Library and Filmoteka Narodowa. Each of these institutions provided access to a range of materials related to Polish and Eastern European cinema. Through this research, I compiled a list of 11 films released in Poland between 1983 and 1996 that can be classified as horror or that incorporate horror-like elements. My primary focus was on uncovering items and academic works specific to the horror genre, but I also explored near-horror genre films—works that incorporate horror tropes but may not be traditionally categorized as such. During my time there, I found reviews, publications from the period and more recent academic books and articles, some of which focused on particular horror films. Moreover, after registering (available only in person) in the Polish library system, I received access to some of the documents stored in the library’s collection, which became available online. Although the documents I needed were only available in the library, having a pass allows me to view the electronic catalogs of all libraries in Poland and remotely monitor the latest publications on my topic.

After spending three weeks in Poland, I went to Germany to continue my research at the Berlin State Library and the Film Archive of the Deutsche Kinemathek. These institutions provide an excellent opportunity to explore archives of Eastern European films and access materials related to Soviet and Polish cinematography. However, I did not find any horror films from Poland or the Soviet Union there. The most useful discovery for me was a collection of rental certificates for Soviet horror films screened at festivals in the former GDR. Their reviews and critical analyses were also important, as they show that East German critics were aware of, and even engaged with, this genre of cinema, which was unconventional in the Soviet Union.

Unexpectedly, my summer research shifted the focus of my dissertation. I had planned to devote my dissertation to Soviet and Polish horror films, as the material available for analysis was very limited, and there seemed to be more parallels than differences: the USSR and Poland were both part of the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War, their film industries were shaped by similar political and cultural factors, including the influence of communist ideology, censorship, and restrictions on artistic expression. However, each of these regimes allowed different levels of freedom of speech, censorship and financial support for the cinema industry. These differences had a significant impact on cinematic expression in each country. Polish and Soviet horror films represent two distinct yet interconnected strands of Eastern European cinema, each reflecting their cultural, political, and social landscapes. After studying the Polish archives and working in Polish libraries, it became clear to me that Soviet and Polish traditions each require their own dedicated research. As a result, my dissertation will focus on Soviet horror films, but at the same time, I will continue examining Polish horror films and this work could develop into my next postdoc-level project. Now I am finishing two articles about Polish horrors for the ASEEES 2024 – the world’s largest and the most prestigious conference of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian studies scholars. The first paper on the 1971 Polish avant-garde horror film about WWII (dir. Andrzej Żuławski) will be presented as part of a roundtable “Ghosts from the Bloodlands: Eastern European Gothic and the War.” The second paper about Polish horror films focusing on ghosts will be presented as part of a panel “Death and Dying in Contemporary Cultural Production.”

Elissa Watters, Art History

September 13, 2024

This summer, with funding from the Visual Studies Graduate Certificate program, I traveled to Toronto, Ontario to do research at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in support of my dissertation, Print as Politics: The Prints of Gerd Arntz and the Cologne Progressives, 1918–1933. My dissertation on what constituted socialist art in Central Europe between the end of World War I in 1918 and Nazi assumption of power in 1933 contributes to literature on political art and art of resistance, particularly during a historical moment of political unrest. Existing literature focuses primarily on the paintings of the Cologne Progressives, a group of artists based loosely in Cologne during the Weimar era, and on how their imagery reflected leftist politics. By contrast, I focus on photo-collages, painted woodblocks, and woodcuts with drawn additions and argue that not just imagery but the process of production itself was crucial to the political engagement of Gerd Arntz (1900–1988) and others in his circle.

The AGO’s vast collection of about 300 prints, drawings, and publications by the Cologne Progressives has been crucial for my research, and it was essential that I visit and see the objects in person, especially given my project’s emphasis on production processes, techniques, and materials, which are often impossible to fully discern in digital reproductions. The collection at the AGO formerly belonged to Angelika Hoerle (1899–1923) until her early death in 1923. At that time, her brother Willy Fick (1893–1967) acquired the many works of art and publications in Hoerle’s apartment. These materials include the bulk of the few dozen surviving works by Hoerle herself as well as numerous prints and drawings by the other four central members of the Cologne Progressives: Angelika’s husband Heinrich Hoerle (1895–1936), Franz Wilhelm Seiwert (1894–1933), and the artist-couple Marta Hegemann (1894–1970) and Anton Räderscheidt (1892–1970). The collection also includes works of art by additional artists loosely affiliated with the Cologne Progressives, such as Fick himself, and other, unaffiliated artists in Cologne at the time, such as Max Ernst. In addition, Angelika Hoerle had amassed many publications that the Cologne Progressives read and referenced and some publications to which they contributed. The collection of works of art and supporting archival materials ultimately ended up in the Toronto when Fick moved to the area to be with his nephew, Frank Eggert, at the end of his life.

During my five days at the AGO, I consulted all the works in the Fick-Eggert collection with the exception of a couple that were unavailable for conservation or other reasons. Such extensive collections of work by the Cologne Progressives are rare, especially outside Central Europe. Looking closely at the works in the Fick-Eggert collection in the AGO’s study room for prints and drawings, under natural light, sometimes with a magnifying glass, I was able to conclude that the artists were often pulling their prints by hand. I also found that they often printed or drew on the versos (backs) of printed sheets torn out of books or even those that were still bound. The versatility in the prints—in techniques, materials, format, and aesthetics—prompted me to rethink my conceptions of the term “experimentation,” which is often used to conceive of originality in print—a medium often associated with reproduction and, relatedly, a lack of originality. The Cologne Progressives did not appear to me to be experimenting with print the way certain other artists, such as Édouard Manet, did. That is, they do not appear to have developed their printed images through three or more states or to have printed the same image on different paper types to see the various aesthetic qualities they might achieve through slight adjustments to the image or in the printing process. Rather, the versatility, I will call it, of the Cologne Progressives’ prints demonstrates their adaptability to the constantly changing political situation in Weimar-era Cologne and Germany at large. For example, one work previously cataloged as a print turned out to be a print with drawn elements that demonstrated the reworking of the image of an already-published print for production as a political poster. I am still figuring out exactly how Hoerle went about adapting the initial printed image; regardless, the transformation of the image took versatility regarding technical skill as well as image redesign.

At the end of my stay in Toronto, I took a daytrip just outside of town to visit art historian Angie Littlefield who is a leading scholar on Angelika Hoerle and the grandniece of Willy Fick. Although Hoerle is no longer the central figure in my dissertation, she enters it at key moments because she, like Arntz, primarily worked in print and drawing, unlike the other Cologne Progressives, whose primary medium was paint. Angie Littlefield was incredibly kind, generous, and helpful, sharing publications, documents, oral histories, and other resources that she had, and directing me to other scholars who might also be useful. After holing up in the beautiful countryside, discussing the peculiarities of the Cologne Progressives over coffee and cookies, I was ready to return to LA to continue research with a new eye for how Arntz’s practice was in some ways quite similar to but in other ways very different from the print-work I had seen at the AGO, despite Arntz’s close connection with the Cologne artists.

Eileen DiPofi, Cinema and Media Studies

September 6, 2024

This summer, I used my VSGC Grant funding to travel to New York City to conduct research at two institutions: the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the New York Public Library (NYPL). I am currently in the early stages of formulating a dissertation that will focus on the transformations in film acting style during the “transitional era” of American cinema (c. 1908-1917). My aim is to interrogate how the period’s formal, industrial, and social changes shaped codes of behavior, gesture, and the construction of the filmic body within the emergent classical Hollywood system. I am particularly interested in how film performance played an active role in the formation of Hollywood’s gendered and racial representations.

Part of my research was focused on a particular film: Lime Kiln Club Field Day (Klaw and Erlanger/Biograph 1913). This film would likely have been the first Black-cast feature film, featuring members of the African American theater scene in New York, but it was never completed. MoMA restored the film’s extant outtakes in 2014, and also houses the Biograph Company’s production records, so I was hoping to collect information on the film’s production. Unfortunately, the production records and camera logs end in 1912 and resume (in a more abbreviated form) in 1914, meaning that the year of Lime Kiln’s production constitutes a lacuna in the archival records. Still, I was able to find traces of Lime Kiln in other Biograph materials: a line in the papers of a former Biograph cameraman and an entry in the Biograph vault records from the 1920s. By supplementing my research at two NYPL locations—the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and the Library for the Performing Arts—I was also able to gather information on the careers of several actors in the film, including the film’s star, Bert Williams. Most interesting to me, in the Phillip Sterling Research Materials on Bert Williams I read handwritten notes from Sterling’s 1960 interview of Williams’s niece (who was living with Williams during the time of Lime Kiln’s filming) in which she shared her memory of his film career.

The other aspect of my summer research involved a more general investigation into the transformations of acting style in the transitional period through a look at the studio widely recognized as the leader of the new naturalist style: the Biograph Company. Here, MoMA’s extant collection of Biograph films proved enormously useful, as I was able to view a selection of films from the 1908-1913 period (in a private theater!) that I have not been able to access elsewhere. In addition, MoMA holds the D.W. Griffith Papers: 36 reels of microfilm spanning the career of D.W. Griffith, who was the primary director for the Biograph Company during the 1908-1913 period. Griffith’s synthesis of an emergent classical film style—including the new “natural” acting—and racist ideologies makes his films and practices a crucial site of analysis for my project. I read interviews with actors who worked with Griffith (including some rather thorough, and at times contradictory, accounts of the rehearsal and filmmaking process) and a wide selection of clippings relating to his various films (including several reels devoted to his infamous The Birth of a Nation). Finally, MoMA and NYPL both held copies of The New York Dramatic Mirror, which I read whenever I had extra time in either archive. This theatrical trade publication, which introduced a film section in 1908, allowed me to follow the discursive shifts in the relationship between stage and screen acting. I was also interested to find the explicitness with which the transformations in film performance were accounted for in the period, with several articles in 1911-1913 providing detailed narratives of the move toward realist acting.

Of course, being in the city where these early-twentieth-century filmmaking and theater practices were concentrated was in itself quite exciting. While it is easy to separate myself from the period and practices I am studying, the daily routine of exiting the archives into a still-vibrant New York City had me thinking more than ever about the afterlives of this period’s intensive change in performance style. My last night in New York, I found myself in the front row of a Broadway show, Stereophonic ($35 rush tickets!), overwhelmed by the naturalistic detail of the performances. After spending several weeks in the archives questioning the ideological complicities of the twentieth century’s penchant for the “real” in acting, I was suddenly reminded that what drew me to performance in the first place was much the same: a fascination with the way the smallest gesture or utterance could seem to puncture into an affective reservoir that feels inaccessible in everyday life. This vertiginous ending to my trip has stuck with me, leaving behind a feeling of complicit kinship with the 1910s commentators who were praising a realism in acting that would echo across twentieth and twenty-first century stages and screens.

Rose Bishop, Department of Art History

August 28, 2024

This summer, with funding from the Visual Studies Graduate Certificate, I traveled to Cleveland to do research at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (RRHF) in support of my dissertation, Idol Makers, Picture Takers: Photography and American Popular Music, 1944-2007. By covering a range of topics — such as the trailblazing “fangirl” photography of 16 and Tiger Beat, how concert venues such as the Apollo and Filmore became sites of multimedia production, and the formation of profitable music photography archives designed for resale of photos in the 1970s and 80s — I hope to describe a multifaceted economy of images, images, makers, and collectors absent from our current ordering of photographic history. Modern music photography emerged at the intersection of fandom, art, and fashion, providing a space in which to debate the possibilities and limitations of photography and its relation to other formats, including magazines, photobooks, television, and film. As one of the largest repositories of music memorabilia, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (RRHF) made for a fitting first stop on my yearlong tour of archives while on fellowship.

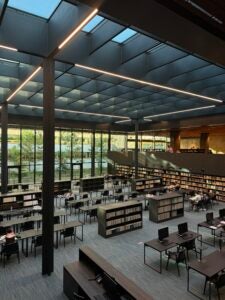

The RRHF library is not in the same complex as the museum and is instead located on the campus of Cuyahoga Community College. I was pleasantly surprised to find a rich collection of music periodicals and photo books available on open shelving and was greatly assisted by a knowledgeable and friendly staff of librarians. For three days I was the only researcher in a beautiful, spacious reading room (which unfortunately I couldn’t take pictures in) and viewed the editorial files of 16 magazine and material pertaining to Michael Ochs, a prominent collector/vendor of music photography. As with any archive visit, there were some disappointments. The 16 editorial records contained zero correspondence or information pertaining to the magazine’s production, and instead consisted of research files on particular musical acts. These folders were revealing in their own way, as they were designed for internal use and contained a wide variety of media, including press clippings, photographs, negatives, and slides. More useful was the library’s large collection of teenage fanzines and music serials, which are (perhaps unsurprisingly) relatively scarce in other research institutions. I hope to return in the Spring for a longer period to view additional collections.

After my visit to the archive, I of course made time to visit the actual museum downtown. The RRHF is a multimedia spectacle unlike anything I’d ever seen before. Loud music plays throughout the dimly lit exhibition space, a soundtrack which seamlessly changes as you move from gallery to gallery. Photography is intermittently used as wallpaper, although it also competes for attention within the displays alongside other objects, including clothing, records, and magazines. The same photographs are also available for purchase upon exiting the exhibition, reproduced on postcards, t-shirts and as limited-edition prints. Seeing a multiplicity of photographic formats at the RRHF helped initiate a new line of inquiry in my research regarding the “reuse” value of music photography. You never know where inspiration will strike— sometimes it’s in the library, other times in a gift shop.