The Creative Eye

Early in her writing career, best-selling author Aimee Bender followed the widely accepted wisdom of the day by diligently jotting down ideas whenever — and wherever — they came to her. The theory, expounded by celebrated writing coaches, was that these notes would work as memory aids, recording inspirational moments, unlocking creativity and making writer’s block a thing of the past. Index cards (small, easily portable) were deemed the perfect tool for the job.

Bender, however, bucked the trend.

“I tried jotting down notes on index cards for a while,” she confides, “and it was almost shocking to me, when I’d sit down to write, how much they didn’t give me.”

Literary sweet spot

Renowned for her surreal plots and characters, Bender, Distinguished Professor of English and director of the Ph.D. Program in Creative Writing and Literature, is the award-winning author of five magically off-kilter novels and volumes of short stories, many imbued with an almost fairy-tale quality. Her best-known work, the 2010 novel The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake (Doubleday) features a heroine, Rose Edelstein, who discovers at age 9 that she is endowed with the ability to taste the emotions of the cook in everything she eats.

So how does Bender come up with her curious and distinctive creative vision?

Certainly not by thinking about writing, something she finds most unhelpful, she says.

“It’s actually counterproductive,” she added. “I want to remove the thinking part from the process as much as possible.”

Instead, she believes that her best material lies just below consciousness in what she describes as a very sweet spot between the tip of awareness and out of awareness.

“I have a really strong belief that that is where the work lives and the work is not necessarily anything that I can predict or know about in advance. I can’t plan it and I can’t impose on it.”

A mysterious alchemy

In almost 30 years of writing literary criticism, author David Ulin, assistant professor of the practice of English and former book critic of the Los Angeles Times, has talked to hundreds of writers about their creative vision. What struck him most is that there is no one, agreed-upon path. Moreover, some writers, he found, are adept at talking about their process, how they develop a story and the ideas they’re writing about, while others are reticent.

“For instance, Zadie Smith is very articulate about what she’s doing and wants to engage in that conversation, whereas Philip Roth doesn’t want to unpack the mystery of the process,” he said. “My understanding is that Toni Morrison maps out everything scrupulously before she begins to write, so the discovery occurs as much in the pre-writing stage as in the actual writing.”

Bender takes the path opposite to Morrison’s, eschewing notebooks, outlines and — especially — index cards, indeed, planning of any sort.

Rather, Bender says she tries to be as open, present and receptive to the world as possible. How that vision is processed onto the page is the mysterious alchemy that becomes the act of writing.

“What I’m always hoping to do is surprise myself and therefore the reader,” Bender said. “I don’t do surrealism to be strange or odd. I do it because it’s the best way I know to get an emotion.”

For Bender, the essence of creative vision can be distilled into two words: “structure” and “surrender.”

“You create a structure so that you can surrender,” she said. “Language provides that structure. It is the holder of what is underneath: that inexplicable force that brings artistic impulse into being.”

Tuning into creativity sometimes involves tuning out surrounding distractions.

Indeed, unlike many novelists whose writing focus is largely character or plot, Bender’s fiction is primarily driven by language.

“I love words and how they relate to each other, how the combination of certain words creates a state of mind or feeling, or an idea that you haven’t thought of before, and that’s also a big part of how I teach — how certain words create a kind of energy, and how remarkable that is.

“In my view, language is actually your guide to where the good material is. If the language has life in it, then that’s probably where your story is.”

To channel her unique creative vision, Bender relies on a self-enforced structure that gives her room to surrender.

“My writing improved a lot when I started working on a fairly rigid schedule,” she said. “Previously I’d just written whenever I felt like it and it had this kind of boundless, daunting feel. Now there’s a discipline to it and I find so much comfort in the idea that I don’t have to write a single word. All I have to do is sit there and it does become so boring, and so dull, that some kind of resource kicks in and eventually I’ll start making something up.”

For this to work, Bender acknowledges, a certain degree of faith in one’s creative abilities is necessary.

“The main thing is the confidence to sit down and to create and to believe that it’s worth my time to sit down, even if I get nothing done for days on end. That’s the hurdle — to think it’s worth that investment in my own imagination, in my own creative process, to sit here.”

Defying classification

Ulin, who in addition to his prolific career as a literary critic is the author or editor of nine books, also prefers to figure out his vision during the writing process rather than mapping it out beforehand.

“For me, that moment of discovery in the act of writing is what pushes me forward,” he said. “That sense of mystery is important to me. I get bored if I know too much.”

Ulin believes that his career as a critic plays into his personal creative vision as a writer of fiction, poetry and narrative nonfiction, where he is interested in the places in which genres blur.

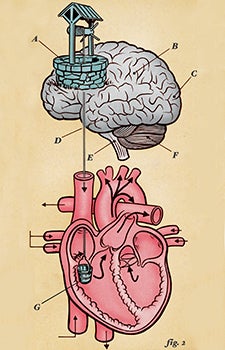

“I think they all come from the same well,” he said. “There’s a great F. Scott Fitzgerald quote to the effect that all writers have a couple of shattering transformative experiences that they keep returning to because that’s what they’re trying to figure out. I keep cycling back to issues of identity, place, time, memory and mortality because I can never resolve them and I don’t think I ever will.”

Maggie Nelson, who will join USC Dornsife as professor of English in Fall 2017, is another genre-busting writer who defies easy classification — at once poet, cultural critic, art writer and autobiographer. The author of five nonfiction books and four books of poetry, her work spans a wide range of topics that includes the murder of her aunt, Jane Mixer; the color blue; queer family; violence in art; and a history of women poets and painters in 1950s New York.

“My process is probably a bit different from other writers in that I typically don’t know what the genre of what I’m working on is going to be until I’ve done a lot of research and taken a lot of stabs at writing,” she said. “There’s research and then there’s the discovery process once you start putting words together on the page.”

For instance, she began her latest book, The Argonauts (Graywolf Press, 2015),in a personal idiom, but after writing for some time noticed she preferred passages where she had veered more toward cultural criticism and decided to weight the book in that direction instead.

Nelson shares Bender’s obsession with language.

“I think because I started as a poet, I have a very hard time reading things with sentences I don’t find lovely,” she said. “In my own writing, I’m impatient with prose that has no rhythm or music, even if it’s critical writing. In the land of poetry, sound and content are one, and I’ve taken that message to all kinds of writing that I’ve done.”

A sense of place

Nelson, who hails from the Bay Area and moved back to California after living in New York for many years, says living in Los Angeles has a strong influence on what she terms “the metabolism” of her writing.

“I’ve watched how the spaciousness of the place has made its way into my intellectual life,” she said.

“When I first moved here from New York and stopped taking the subway and started driving, I noticed that instead of thinking in fragments — which is how the subways work, where you catch conversations and see different things every minute — I found myself plotting the arc of my books and imagining their form as I drove. That has allowed me to take on larger projects because I’ve had the mental and physical space to lay them out.

“In New York there’s a lot of talking. I’m a loquacious person and I loved being with all that speech, but in a strange way it never allowed me to be quiet enough to hear what was going on in my head. Since I’ve been here, I learned how to pay more attention to following my interests in a more expansive way.”

Nelson’s sensitivity to place is echoed by New York Times best-selling novelist Marie Lu ’06. Lauded by critics, Lu has already established herself as a bright star in yet another genre: young adult fiction.

Her creative vision finds expression in her remarkable ability to take the darker elements of real life, either current or historical, and project them into the dystopian fantasy worlds she builds in her fiction — worlds that offer the possibility to hold up a mirror to reality.

“Writing is my own form of therapy,” Lu said. “It’s my way of making sense of the world.”

Lu credits her first job in the video game industry for kick-starting her creativity and motivation as a writer. It also inspired her latest novel, Warcross, due out from G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers in fall 2017. The book explores a dystopian universe dominated by a video game that becomes a way of life for its millions of fans.

Warcross is set in Tokyo, a city Lu visited last spring and found mesmerizing — a quality she was determined to recreate in her novel, in which her characters wear contact lenses that overlay another reality on top of the real world.

“I wanted to play with the idea of changing our environment so we’re all living in a different reality,” she said. “Whatever you want to see can be downloaded into your vision, so not only do you see looming skyscrapers, you also see dragons flying in the sky or stardust raining down.”

That might sound like harmless fun, but Lu is intent on exploring the darker side of the moral ambiguities arising from such technological advances. “For instance, those who walk through a poor neighborhood full of broken windows and homeless people could download a different virtual reality overlay, so instead they see clean streets with beautiful sidewalks swept clean of problems and suffering. That’s disturbing for obvious reasons.”

Sowing the seeds

Lu studied political science and biology and says those subjects still inform her writing today.

“The courses I took at USC Dornsife sowed the seeds for the topics that I choose to write about now,” she said.

Writers may have widely different processes, but most agree that their vision springs from a deeper place than logical thought.

Her first series, Legend, envisions what our future might be like a hundred years from now by taking current issues and extrapolating from them.

“I thought, ‘What if our two political sides were pushed to such extremes that we figured we can’t live with each other anymore, and the United States splits into two different countries.’”

Set in a futuristic vision of L.A., now under martial rule, Legend depicts USC as a military university.

“Downtown is half-flooded, and steel skyscrapers like the U.S. Bank Tower rise out of a vast lake. They’re abandoned, but people swim over to them to sit on the sides and dangle their feet in the water,” Lu said. “It was fascinating to take what was familiar to me, the streets and buildings that I knew so well from living in L.A., and tweak them to fit a dystopian vision.”

Lu also taps into her background as an artist to make detailed drawings of her characters before she starts writing about them.

“If I don’t draw them I have trouble understanding who they are. This physical exploration of character also helps me figure out the rest of the story.”

Music is also key to Lu’s creative process.

“I have a lot of trouble writing in silence,” she said. “It’s too distracting, too loud.”

She overcomes that loudness by curating playlists tailored to each novel. She wrote Warcross to electronic music and soundtracks from video games and sci-fi movies interspersed with mood music to help her get into the right frame of mind to write certain scenes.

Lu also travels extensively. A trip to Canada to see the Northern Lights resulted in a rich haul of sensory detail that she used to good effect in The Young Elites.

“There’s just no replacing the feeling of actually standing in a place to understand it with all my senses,” she said. “In Canada, it was 50 below zero and I could feel the surface of my eyeballs freezing. Ice crystals formed on my lashes, and when I took a breath, it hurt because the air was so cold. I don’t think I would have been able to write those scenes so successfully without having actually experienced that kind of cold.”

Exile and identity

Place also occupies a central role in the creative vision of Safiya Sinclair, a doctoral student in creative writing and literature at USC Dornsife. An award-winning poet, Sinclair earned a prestigious 2016 Whiting Writers’ Award for her first full-length collection, Cannibal (University of Nebraska Press, 2016).

Born in Jamaica into a Rastafarian household, Sinclair says she always felt like an outsider in her native land where Rastafarians — a minority — suffer discrimination.

“My siblings and I always felt some sense of otherness, of being an outsider, something akin to a kind of exile, feeling like a stranger in your own home, your own body, your own country.”

For Sinclair, writing poetry was a saving grace, a way to reason through feelings of exclusion and make sense of them. Using her poetry to shatter stereotypes and engage social issues, her work explores themes of identity, race, misogyny and exile.

As part of her thesis, Sinclair is writing a prose memoir about growing up as a young Rastafarian woman under a strict patriarchy. “I realized I wanted to interrogate why I was being treated differently than my brother or other boys I knew. This idea of womanhood as a place of exile is a constant source of interest for me.”

Sinclair’s research also focuses on the violence of language.

“So many words and expressions in our everyday vernacular are rooted in violence against women,” she said, “from describing a singlet as a ‘wife-beater,’ to saying ‘knocked up’ instead of pregnant. I’m interested in how these words come down to us and how they contribute to furthering violence against women because the language we use shapes the world we live in.”

Imagery is crucial to Sinclair and her poetry uses recurring images of the sea and of the bougainvillea and hibiscus that bloom freely in Jamaica.

“A well-crafted image can convey anything,” she said. “It can convey pain, violence or joy. It can say the thing without saying the thing, by showing you. It’s a way to subtly give the reader an invitation into the poem and the meaning of the poem or the ‘why’ of the poem without being pedantic. It’s an opportunity for the poet to be painterly.”

The sea is always in the background of Sinclair’s poems, even if it’s never named or mentioned. “The sea is the lyric landscape that I find my mind wandering to when I’m entering into a poem,” she said. “I was born in a fishing village right on the beach and the sea is always something I’m trying to echo, whether rhythmically or metrically, in my work.

“The landscape of memory, of growing up in Jamaica with its wild and impenetrable tropical vegetation, is also a rich place for me to frame many of my poems. I’m interested in trying to mirror this natural world on the page.”

As she writes, Sinclair reads her poems aloud because — as she notes — “this is where the words and music combust, and the poem’s energy emerges.”

Keeping the faith

If Sinclair grew up under a strict patriarchy, Bender’s youth was strongly influenced by the liberating qualities of modern dance. The daughter of a psychoanalyst and a choreographer, her childhood resonated with poetry, fairy tales, theater, and the intimation from her father that the exploration of feelings through words was worth pursuing.

“That combination of psychology and theater was potent and compelling to me,” Bender said. “As a result, the conflict between what’s on the surface and what’s underneath is endlessly interesting to me in terms of how we navigate each other and ourselves.”

She has participated in many community outreach projects, from teachingcreative writing to underserved elementary students at the USC Family of Schools, to doing theater improv with psychiatric patients.

“It’s been a pleasure for me to try to loosen up the restrictive thinking around fiction in any way I can with my own work and as a teacher,” she said. “It’s exciting for students to write something that shocks them or makes them laugh. I think that’s an incredible sense of discovery and openness, so I try to do as much as I can to facilitate that.”

Bender tells her students to keep faith with the process, that if the story is starting to work it will develop on its own terms — if they can let it. Too often, she says, a student writing an interesting story will introduce a major twist because of anxiety over a perceived lack of plot.

“Suddenly the police will arrive, or there’ll be a car crash,” she said. “It’s ludicrous and almost funny, but you can feel that it comes from this impulse to make something happen in this false way. My wish for my students would be for them not to make choices that feel contrived, but to make choices that feel organic.”

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Spring/Summer 2017 issue >>