Rimbaud experts forge new insights into French poetry’s beloved bad boy

While translating Arthur Rimbaud’s great symbolist poem “Le Bateau Ivre” (“The Drunken Boat”), poet Mark Irwin, associate professor of English at USC Dornsife, puzzled for weeks over one particularly challenging line.

“The literal translation was ‘Rain falling like lead from the sky,’” Irwin said. “Trying to avoid the cliché in English, I translated it as ‘When July rained down its hammers,’ so I made up a completely different idiom. But that’s hard to do. That line took me a month, and it was exhausting.”

Mark Irwin, associate professor of English. Photo by Steve Cohn.

The final translation of the 100-line poem which appeared in The New England Review took Irwin three years to complete. Such is the challenge of translating Rimbaud, one of the most influential poets of all time. It is a challenge that Irwin has embraced. His new book, Zanzibar: Selected Poems and Letters of Arthur Rimbaud, containing 30 new translations of Rimbaud’s poems, is due out next year.

The project is a collaboration with Irwin’s friend and colleague Alain Borer, professor of the practice of French at USC Dornsife. One of the world’s foremost experts on Rimbaud, Borer is the owner of an 8,000-volume library on the poet.

Zanzibar will contain a 15-page introduction by Irwin. Borer will contribute a 25-page essay.

“This will be the first book in which the translator is himself a poet and the scholar is writing poetically about Rimbaud,” said Irwin, whose ninth book of poetry A Passion According to Green (New Issues/Western Michigan University Press) will be published next year.

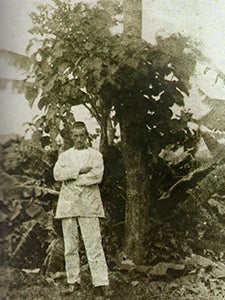

This 1882 photograph shows Rimbaud among banana trees in the walled city of Harar in Eastern Ethiopia. Photo courtesy of Alain Borer.

Zanzibar will also be unique, Irwin said, because it will contain around a dozen rare documents, including maps, sketches and photographs from Borer’s private collection. Among them are Rimbaud’s sketch of the stretcher he designed after developing bone cancer, a photograph of Myriam, Rimbaud’s mistress in Abyssinia, and a number of self-portraits.

“Alain was the first writer to completely chart the world of Rimbaud and make it present for other people,” Irwin said. “This will be the first book where the poetry is presented together with other documents so readers can get a feel for the historical and cultural presence, as well as the poems themselves.”

Irwin chose the title Zanzibar because of Rimbaud’s frequent references to the East African archipelago in his correspondence as an ideal place that existed beyond the prison of his body.

Borer welcomed the choice of title, “It is the dream island, the paradise he never reached and this state, ceaselessly postponed, which corresponds exactly to his quest,” he said. “We all have our Zanzibars.”

“A monster of purity”

A photograph of Rimbaud’s mistress, Myriam, a Christian Abyssinian woman with whom the poet lived with for six months in 1884 in an apparent effort to lead a “normal” life, before abruptly sending her away, declaring, “I’ve had this masquerade in front of me for long enough.” Photo courtesy of Alain Borer.

Both Irwin and Borer were marked by the poet from a young age.

Irwin first read Rimbaud at the age of 15.

“Rimbaud was the poet who made me want to become a poet, more than any other. I’m not sure that I understood the poetry at that time but I felt it very deeply,” Irwin said, adding that it was Rimbaud’s frustration with life that inspired him to write.

“French critic, Jacques Rivière, called Rimbaud ‘a monster of purity,’” Irwin said. “I always thought that was the best characterization. He was constantly looking for the essence of everything. That was why one place wasn’t enough for him. He couldn’t stand being trapped in one body. He was looking for something beyond that body, for some ailleurs absent, or “absent elsewhere,” as Alain calls it. That is the whole key to Rimbaud.”

As a young man, Borer followed in Rimbaud’s footsteps, traveling to Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) at the age of 27, the same age Rimbaud was when he made the original journey. There, Borer made a film, Le Voleur de Feu, (The Thief of Fire) with poet and composer, Léo Ferré.

An adolescent prodigy, Rimbaud is also remembered as a notorious libertine. “There is a wonderful and moving letter, which I translated in the book, in which Rimbaud writes, ‘If you want to be a great poet, you must seek a complete derangement of all the senses,’” Irwin said.

An 1877 sketch of Rimbaud traveling by his lover and fellow poet, Paul Verlaine. Image courtesy of Alain Borer.

The theory worked for Rimbaud who, in six brief years, wrote some of the greatest poems in the French language. Then, at the age of 21, he stopped.

Instead of writing, he sought to quench his insatiable desire for the “absent elsewhere” by traveling extensively, notably to Abyssinia and the Middle East where he traded coffee, silk, rifles, pepper, gold and ivory and possibly killed a man during a quarrel while he was overseeing a construction site in Cyprus.

“When he stopped writing, Rimbaud began to enact physically, to embody all the places of the imagination, and in that way he became a sort of pioneer of performance art,” Irwin said. “At the end, his life was an action film. He is unique among all poets, a complete enigma.”

What makes Rimbaud unique, Borer argues, is the fact that not only does he abandon poetry, he was also ahead of his time in inventing new forms, including free verse and prose poems that were forerunners to Surrealism and the Beat Generation.

“To understand Rimbaud you have to think of him as a sphinx placed at the entrance to the question of poetry,” he said.

Rimbaud’s poems ask essential questions — Which place? What time? How to seize time? How to do it?

“These are the eternal questions that we are mining for answers,” Borer said. “Rimbaud asked the questions but never answered them, because there are no answers. He was right.”

Borer is the author of 12 books on Rimbaud, which have been translated into 18 languages. Among them are Adieu à Rimbaud and L’Œuvre-vie (Édition du Centenaire, 1991) marking the centenary of Rimbaud’s death; his translation into French of Irish literary critic Enid Starkie’s celebrated biography of the poet; and his combined essay and travel journal Rimbaud en Abyssinie (Fiction & Cie, 1984), which was published in the U.S. by William Morrow in 1991 as Rimbaud in Abyssinia. You can learn more about Borer by exploring his website at www.alainborer.fr.