Historian uncovers the legacy of Black Caribbean women who helped build the Panama Canal

Before Panama became the focus of Joan Flores-Villalobos’ research, it was a place of a more personal importance. Though she was born in Maracaibo, Venezuela, and held no personal connection to Panama as a child, during her undergraduate years some of her family members started to migrate to the Central American country, and she grew more interested in the lives and histories of Panama’s immigrants.

“My topic clearly comes from a personal place of wanting to think more about migration and women’s role in it,” said Flores-Villalobos, an assistant professor of history at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

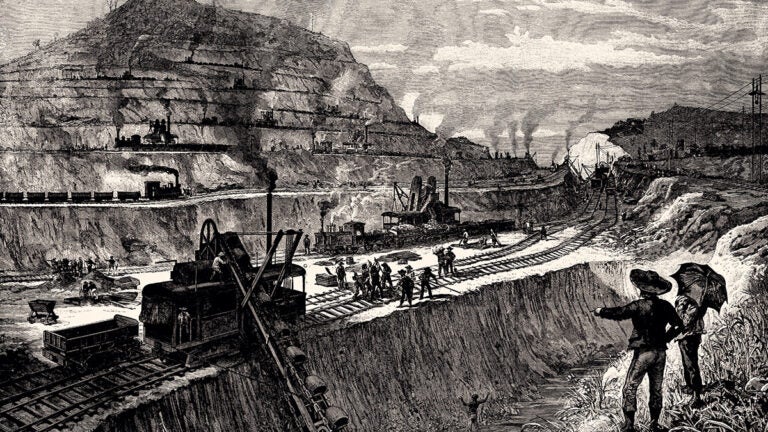

So, drawing on her undergraduate work in Black studies, Flores-Villalobos set out to explore the history of Black Caribbean women who migrated to Panama during the construction of the Panama Canal, which took place from 1904 to 1914. The stories of those workers are seldom heard, Flores-Villalobos said.

“I went to the national archives in [Washington,] D.C. and realized there was such an enormous silence on Black women, and I was shocked. I thought, ‘It’s so obvious women also came. Why are they so hard to find?’”

A personal path from Venezuela to the U.S.

Joan Flores-Villalobos studies the diaspora of Black women in the Caribbean. (Photo: Courtesy of Joan Flores-Villalobos.)

Flores-Villalobos grew up in Caracas, Venezuela, but moved to Houston, Texas, at age 16. The adjustment wasn’t that hard — the Venezuelan community in Houston is so large that one could live a full life without ever speaking to a non-Venezuelan, she said — and her sizable public high school had enough Spanish-speaking students that she was able to integrate easily.

When it was time for college, Flores-Villalobos had no idea where she wanted to go. In Venezuela, college is free. Here, she was confused about the different types of colleges, the application process and financial aid. But she did know what she didn’t want.

“I just went onto, like, Ask Jeeves, and I typed ‘best college that doesn’t make you take math,’ and it came up with Amherst.”

She attended Amherst College in Massachusetts and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Black studies. Later, she earned her master’s degree in media studies from the University of Texas, Austin and her Ph.D. in African diaspora history from New York University.

Caribbean diaspora

The diaspora of Black women in the Caribbean has interested Flores-Villalobos throughout much of her undergraduate and graduate career. Although much has been published on the construction of the Panama Canal, the voices of the Black immigrants who migrated to the country to work on it are seldom heard, and this is especially the case for the Black migrant women, Flores-Villalobos said.

The archives of the U.S. company that built the canal had very little information, so she went to archives in Panama, Barbados, Jamaica and the United Kingdom. Her work will soon be published in a book, The Silver Women: Gender, Labor, and Migration at the Panama Canal.

The depressed economic situation of many Caribbean islands in the long aftermath of emancipation from the British empire created a population that had little economic opportunity and was eager to travel for work at a massive construction project, especially one as well funded as the Panama Canal.

Flores-Villalobos said the migration of Caribbean women to Panama followed the path of similar migrations: Some women came with their husbands or brothers, some came for adventure and others came for their own economic opportunities.

“I think people rarely think of women as being principal economic actors; when someone thinks of a migrant worker, it’s nearly always a man. There were no ‘official’ jobs on the canal construction open to them, but there were other jobs, like domestic service and selling food,” she said.

Migration and its aftermath

After the canal’s completion, some immigrants returned to their home islands and some went on to other areas with projects backed by U.S. investment, like sugar plantations in Cuba. Some migrated to the U.S. itself, settling in New York neighborhoods like Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brooklyn. But many of the immigrants stayed in Panama.

“There is a distinct community of ‘Afro-Panamanians’ — though some call themselves ‘West Indian Panamanians’ or ‘Afro-Antillieans.’ There is food, music, artistic traditions, and a political history in Panama that was indebted to West Indian immigrants,” Flores-Villalobos said.

At the time of the canal project there “wasn’t a developed sense of something like ‘legal’ or ‘illegal’ immigration,” Flores-Villalobos said. However, once the project was completed and those construction jobs had disappeared, relations between the Panamanian government, its people and the migrants became more complicated and contentious, and there was a rise in anti-Black xenophobia. Laws were introduced in Panama that prohibited West Indians from immigrating to the country and stripped citizenship of children born to West Indians in Panama, for example.

“You can see the real and perceived effect of unemployment and economic crisis, but more importantly you can see the misplacement of blame onto immigrants when of course these mass changes in Panama are due to imperial power,” Flores-Villalobos said. The U.S. and the canal company were more to blame for the situation, she added, because they created an enclave of the economy and encouraged mass migration to fill it, then abruptly took the jobs away once the project was over.

The strife created by unemployment, economic crisis, racism and displacement of blame is an important illustration of the crisis facing the U.S. today, Flores-Villalobos said. She noted that for her next course, on Afro-Latin America, she plans on turning away a bit from the “mestizo/Latinx” migrant — the one that most often leaps to mind when immigrants are mentioned — to look at those featuring marginalization and inequality on several levels: Black immigrants, Black Latinx immigrants and African immigrants.