Living Art

Art historian Suzanne Hudson can’t keep up with the tally, the number of invested observers — critics, curators and even artists themselves — who have come forward to whisper last rites. Sifting through centuries’ worth of research, Hudson has noted, time and again, how painting’s role as a means of creative artistic expression has been challenged, deemed irrelevant or characterized as simply a quaint reminder of times past — its very existence as a medium threatened.

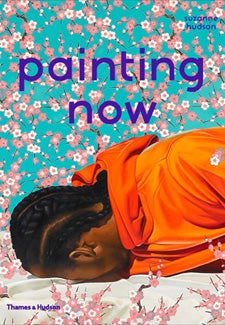

Photography posed a danger in the 19th century. Later, the artist and Dadaist Marcel Duchamp’s adoption of the “readymade” coincided with his breaking with “retinal art,” his term for brush-to-canvas studies. They, however, are merely two early, critical examples that Hudson, associate professor of art history and fine arts at USC Dornsife, points to in her new book, Painting Now, a global survey of contemporary painting that argues for the vivacity of the medium in the digital age.

Despite painting’s ubiquity (and constancy), these debates didn’t diminish — instead they gathered momentum through the 1960s (post-Pop Art) and beyond.

“The canvas corpse was a rallying point in the ’80s,” Hudson said. “Beyond concerns about the end of modernism were others regarding the viability of painting as such. In response, some advocates countered that painting was trans-historical, subject neither to critical fashions nor the politics that impelled them. It was a stalemate that over-determined the writing about painting in the years that followed, with the death and rebirth of painting announced over and again.”

Painting Now, she hopes, will provide both a historical framework and a new philosophical context to explore painting as a vital art form.

Art or aspirational object?

Four years in the making, the book, in a certain way, is a document that mirrors Hudson’s personal creative path. A former painter and in-the-trenches art critic, she’d found herself drawn into a medium that had been shunted to the side. “By the time I got to it in the early 2000s, I was seeing essentially everything but painting. People were very scared to be working in painting because, as a hangover from the ’80s, it was understood in many art school contexts as a contaminated medium,” she said.

Much of the scorn, Hudson explained, had to do with the role of the marketplace. From the ’60s onward, she explained, “There was an assault on art as stable, singular objects that could be collected. Seemingly exemplifying the commodity status of a wider range of work, paintings were trivialized as reducible to bourgeois decoration or kinds of lamentable, if aspirational, objects. To be an avant-garde, critical, serious artist invested in ideas you couldn’t accomplish this in painting.”

Painting Now defends the art form’s stalwart place as a creative medium.

For Hudson, however, there is another potential interpretation. In her reading, painting “becomes more possible after [the advent of] conceptual art — when the idea comes first and then you have to figure out what to do with that idea in material form. There was no reason why painting couldn’t be a form with which to manifest ideas, and through which to bring them into being.”

Reframing the debate

While still in graduate school at Princeton, Hudson had been chronicling the scene while working as a critic for Artforum. “I began writing about painting shows when no one else wanted to write about them. I had a lot of space to really develop my ideas on a case-by-case basis.”

That monthly visibility brought her to the attention of Thames & Hudson, who published Painting Now in March. “There aren’t that many people who write regular criticism and embrace a scholarly, more historical perspective, so that’s how I ended up being commissioned to do this project.”

Hudson wanted to go beyond a decade-by-decade historical exploration, not only flipping the debate on its head, but also turning the context inside out, so readers could see it anew.

“Painting has really developed in the last 20, 30 years, but our language around it hasn’t,” she noted. The discussion still seems to circle around the debates of the ’80s and the culture wars. “I don’t want to trivialize the importance of the postmodern polemics, but I think these debates too need to be historicized. The cultural and political conditions have changed since the ’80s and we haven’t really accounted for that. I wanted to show people where we are now.”

She spent two years immersed in research — reading, looking at art, and attending festivals, exhibitions and fairs. “I wanted to do my due diligence and research as much as I could. I was also humbled by the task to make something synthetic in a field as nascent as its record is venerable. But then it sort of became this question, ‘What do I do with all of this stuff?’”

A conversation starter

The solution came in the book’s provocative configuration.

“I think the obvious organization would have been a chapter on landscape, a chapter on abstraction, etc.,” she said. “But I wanted the book to be both about the specificity of painting and the larger organizational structure of the art world in which all of this work is coming into visibility and even prominence by acting upon these structures.”

As well, Hudson thought it was important to examine the mechanisms dedicated to circulating the work. “I wanted to address the technological transformations — things like JPEGs viewed on backlit screens — that have made painting’s distribution so radically different than we have been accustomed to seeing.”

Hudson regularly teaches courses in post-war history of art and museum studies. She’s also designed a summer course in contemporary art and art writing, where students spend a month in New York, often witnessing these discussions firsthand and in real time.

Her wish for the book is similar to that for her students following each term. “I hope that it will make people curious to know more, whether they are consummate insiders or are people who pick it up randomly and want to learn something about contemporary art.

“Not every conversation needs to be about the market,” she added. “I think the market is often kind of an alibi and stops a conversation rather than starts it. It’s the prices, rather than about what the thing is. I want to get people thinking that there are other questions that need to be asked. And if they don’t like the ones I pose, so much the better. I hope that the book becomes part of a very robust new set of issues.”