Journey into the Grotesque

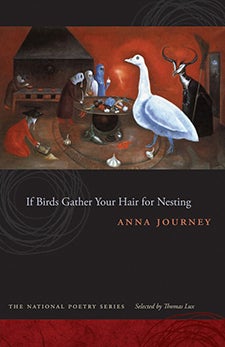

Described as “magical” by provocative filmmaker David Lynch, Anna Journey’s first book of poetry, If Birds Gather Your Hair for Nesting (University of Georgia Press, 2009), was selected for inclusion in the National Poetry Series. Journey, who joined USC Dornsife in August 2014 as assistant professor of English, has since published a second poetry collection, Vulgar Remedies (Louisiana State University Press, 2013), and is working on a third. In 2011, she was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship for Poetry.

Susan Bell: Much of your writing is inspired by the grotesque. Tell me about your interest in that.

Anna Journey: My interest in the grotesque began around the family dinner table. My parents, who grew up in Mississippi, love to tell stories, which is an inclination that draws from the storytelling tradition of the American South. Throughout my childhood, my mother told stories that would’ve been banned in most other households, at least while people were still chewing their food. Some of her favorite dinnertime tales included Trotsky’s death by ice axe to his skull; an apocryphal Civil War-era remedy for dysentery that involved using a piece of dried corncob like a cork; and the infamous pet chimpanzee Travis, who went berserk one day and gnawed off a woman’s face.

Simply put, the grotesque involves the clash of incompatibles — both in the work (the story or poem) and in the response (of the audience). In the grotesque, humor collides with horror, attraction with repulsion, and beauty with ugliness. As a writer, I find this unstable dynamic irresistible and especially useful in creating tension in a work of literature.

SB: Tell me about your most recent book.

AJ: My most recently published poetry collection mixes fragments of personal anecdote (family stories, childhood memories, encounters between lovers) with peculiar or fabular details (folk superstitions, strange scientific facts, magical characters). More specifically, there’s an undergarment primed for nuclear apocalypse (the gas-mask bra), a nostalgic winged spirit who basks in the molasses-tinged air of a Texas barbecue joint, and a leather-clad boy who likes to suck people’s eyeballs.

Selected for The National Poetry Series, Anna Journey’s debut collection of poems invites the reader into her macabre universe.

SB: Tell me about the classes you are teaching at USC Dornsife. What do you particularly enjoy about teaching here?

AJ: During my first year as an assistant professor of English, I taught writing workshops in poetry as well as creative nonfiction and a general education course called “Misfits and Mysteries: The Grotesque in Recent American Literature.” In the latter course, my students and I explored the various ways poets and fiction writers employ grotesquerie in their work.

During the fiction unit of the course, my students and I examined short stories by the renowned 20th-century author Flannery O’Connor and the contemporary writer Aimee Bender [professor of English and director of the Ph.D. program in creative writing and literature]. Bender often employs grotesquerie to create fables of grief and human vulnerability that resonate with aspects of magical realism.

I always enjoy encountering bright and talented students in my classes, but what I find especially exciting is when a student from a major other than English discovers a new understanding of and passion for literature. Each semester, my biggest reward is seeing that spark, that connection students make with a particular poem or short story, that understanding and excitement that — I hope — will lead to love and continue long after the semester has ended.

SB: Do you have a writing routine or process? Is there a “best time” for you to write?

AJ: I believe, to paraphrase Randall Jarrell, that if you want to get struck by lightning, you have to be there when the rain falls. Inspiration is great, but it can be a passing fancy unless you have the chops and discipline to do something with it. For me, being there when the rain falls means reading for long stretches of time, usually out loud to myself. Reading is what makes people better writers. The alchemy comes not from talismanic external factors — like time of day or a special pen — but from language itself as I sit down and allow the process of writing to become one of surprise and continual discovery.

SB: How do you know when a poem is finished?

AJ: I have to agree with Paul Valéry: “A poem is never finished, only abandoned.”

SB: What are you currently working on?

AJ: I’m currently working on a personal essay called “Birds 101,” named for the two-day taxidermy class I took a few weeks ago in downtown Los Angeles in which I preserved a handsome European starling. I’m interested in how taxidermists and poets engage aspects of lyric time as they “freeze” a moment and defy the natural outcome of mortality: vanishing.

SB: What inspired the title for your next collection of poetry The Atheist Wore Goat Silk?

AJ: I took the working title for my third book, The Atheist Wore Goat Silk, from a poem by that same title. The poem draws its inspiration from the realms of science and family. I think of the poem, I guess, as an ars poetica: that genre of poetry that aims to describe what it means to write poems, to describe “the art of poetry.” The poem with the word “atheist” in its title ends up being a piece all about belief. It’s about believing in the primacy of the imagination.

SB: What words of advice do you have for students who want to become writers or poets?

AJ: Read broadly and eclectically. Try to write the kinds of poems, essays, or stories that you most like to read. Developing a mature voice takes a number of years, and becoming well read is the project of a lifetime, one that provides an ongoing source of inspiration, instruction and pleasure.