From history major to spy: an unexpected career twist

Tracy Walder has to be America’s most unlikely spy. Born in Southern California’s San Fernando Valley, Walder grew up in nearby Orange County. She was a sorority girl majoring in history at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences when she decided to apply to the CIA on a whim after spotting the agency’s booth at a careers fair on USC’s University Park campus.

Growing up, Walder had never imagined herself as a spy or a secret agent, but the former home-coming princess did have a secret she kept from her sorority sisters: She was a poli-sci nerd obsessed with keeping the world safe from the threat of global terrorism.

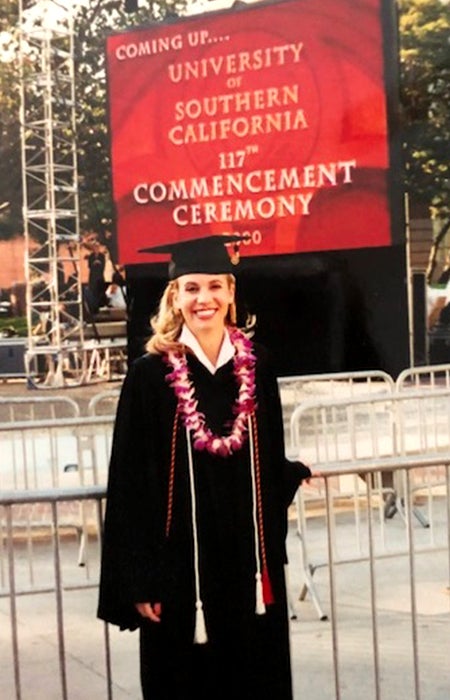

Walder had another secret, too. As an infant she had been diagnosed with hypotonia (floppy baby syndrome). Doctors told her parents she would never walk or go to college, never mind achieve much in life. And yet, after defying the odds to earn her bachelor’s degree in 2000, Walder ended up traveling to global hot spots to successfully interrogate some of the world’s most dangerous terrorists for the CIA before moving to a second career with the FBI.

As a CIA special operative in counter-terrorism, Walder traveled extensively in the Middle East, Europe and Africa, bringing down two plots involving weapons of mass destruction and identifying and charting key leaders of terrorist cells planning poison attacks around the globe.

As an FBI special agent assigned to the Chinese counterintelligence squad, she helped uncover two naturalized American citizens in Los Angeles County who were stealing nuclear submarine blueprints and sending them to China. Both were jailed for their crimes.

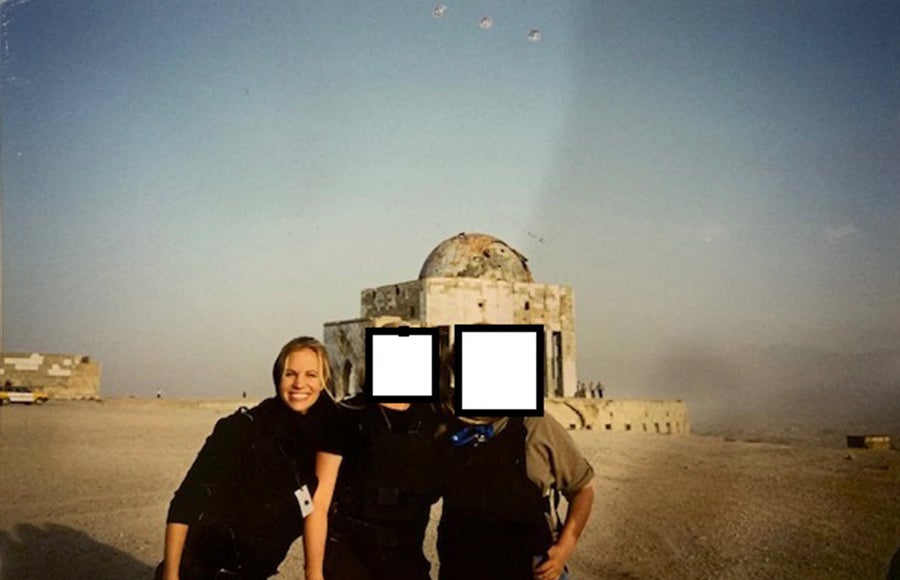

Walder is most proud of her work at the CIA to stop poison attacks in Europe but says her most exciting mission was spent in a war zone questioning suspected terrorists in an undisclosed location she describes as being “as stark as the surface of the moon.”

“It was just the total polar opposite from the life that I lived and the place that I was from,” she says.

Walder reveals all about her extraordinary life journey in her recently published book The Unexpected Spy: From the CIA to the FBI, My Secret Life Taking Down Some of the World’s Most Notorious Terrorists (St. Martin’s Press, 2020). Or at least she would have revealed all if the CIA had not redacted portions of the book for national security reasons.

Tracy Walder stands in a war zone with two unidentified colleagues during her time as a CIA special operative.

“I was not going to publish a book without getting the CIA’s approval,” Walder says. “Some people do it, but I find that to be very disrespectful.”

Although it meant that she had to rework the book five times to make it readable after the CIA ruled that many words, phrases, sentences or entire paragraphs could not be printed, Walder was adamant in her determination not to give away anything that could be damaging to either the organization or her country’s security. She and her publisher decided to leave the blacked-out text as it stood so readers could see where her words had been redacted — a decision that proves remarkably effective in underscoring the secret nature of her work.

Reading the book, it soon becomes apparent that Walder’s loyalty to USC is as iron-clad as her loyalty to her country.

In a chapter titled “Trojans Rule,” she describes fiercely defending USC and California during a heated argument with a CIA colleague who denigrated both the school and the state.

“USC Dornsife made me successful in my career,” she says. “USC Dornsife is a huge part of who I am, it’s a huge part of who I’ll always be, and it made me who I am.”

The path to becoming a spy

Born in the L.A. suburb of Van Nuys, Walder moved to Orange County at age 7 with her family. Her father was a psychology professor at Chapman University while her mother worked as a bank teller.

It was thanks to her mother’s determination that Walder overcame the hypotonia diagnosis. Judy Schandler encouraged her daughter to walk and enrolled her in dance classes as a toddler — a hobby Walder pursued at USC.

At school, Walder hid the hypotonia but was bullied by girls from third to ninth grade, something she puts down to her early growth spurt, adolescent acne and wonky, pre-braces teeth.

Walder found a creative outlet in dance and developed grit.

“My parents weren’t people who let us wallow,” Walder says. “I think maybe that helped me develop resilience because I didn’t really sit around and feel sorry for myself.”

By the time she got to USC, Walder, a second-generation Trojan with long blonde hair and a fondness for pink, fitted seamlessly into sorority life at Delta Gamma.

Walder’s father, Steven Schandler, earned his Ph.D. in psychology from USC Dornsife in 1976. From ever since she can remember, Walder grew up surrounded by USC memorabilia and Trojan football.

“I have a picture of myself at three months old in a USC onesie,” she says. “Growing up, I loved going to the football games, I loved the kind of East Coast look of the school, I just loved everything about it.”

When it came time to choose where to go to college, Walder didn’t even consider another school.

The same kind of gut instinct took hold when she spotted the CIA booth at the careers fair on Trousdale — even though she initially doubted her eligibility.

“I knew that there was a group of people in the CIA who looked at terrorism,” she says. “I went over there. I remember saying, ‘Oh, I’m a history major, I’m not qualified for this,’ and [the CIA recruiter] said, ‘No, actually a history major would be great at this.’ So I applied.”

In November of her senior year, after passing a rigorous selection process, Walder was offered a job upon graduation. That year, she also participated in USC Dornsife’s Washington, D.C. Program, interning for then Senate Minority Leader Thomas Daschle — an experience she describes as “life-changing.”

History: a superpower

Far from being a disadvantage, as she had feared, Walder discovered that her major had supplied her with the very skills that enabled her to succeed in her new job.

When Tracy Walder graduated from USC Dornsife in 2000 with a bachelor’s degree in history, she had already accepted a job with the CIA.

“One of the great things about being a history major at USC Dornsife was that I was always encouraged by my professors to take a multifaceted view of things — what we would call a 360 approach to a fact, a problem or an instance in history. At the CIA, whether you’re an operative, whether you’re an analyst, whether you do tech, that’s 100 percent what the CIA is all about. I think that absolutely made me a better officer.”

Walder also found that being able to communicate her ideas succinctly using facts — something that her history degree had trained her to do — was crucial.

“CIA administrators and American policy makers don’t want to hear just hypotheses necessarily; that’s dangerous. We had to have the facts, and being a history major was quite essential, in my opinion, to my success at my job.”

At The Farm, the CIA’s legendary training facility in Virginia, Walder successfully learned surveillance, how to handle small arms weapons and how to drive defensively. However, as a chapter in her book titled “Crash and Bang” recounts, she found the latter challenging.

“Driving stick did not come naturally to me, let’s just put it that way,” she says.

A new understanding

Although Walder politely declines to answer a question about her training in interrogation techniques, in her book she describes in detail how she succeeded in establishing a rapport with a suspected terrorist, bringing him a carefully selected piece of fresh fruit every morning and asking him if he missed his mother as she missed hers. It was an effective strategy.

“The best way to get information from someone is to get them to feel that they have something in common with you, that you care about them and their life, so that they will trust you and then give you information,” Walder says.

Talking to terrorists enabled her to gain an understanding of what made people join groups like Al Qaeda.

Those at the highest echelons of terrorist organizations actually wanted to be terrorists, she notes. However, those occupying the middle and lower ranks were often there for other reasons — frequently, she says, “because they needed a place to be.

“A lot of them were orphans, abandoned by their families — sick, chronic illnesses, never went to school — and Al Qaeda comes in and says, ‘Hey, we’ll educate you, give you three meals a day, give you vaccines and medicine.’ That helped me understand what makes people susceptible to terrorism.”

After four years serving in the CIA as a staff operations officer, Walder left to join the FBI.

“I loved doing counter-terrorism, but I just couldn’t live overseas anymore. I wanted more stability. I wanted to be in one place. I guess I was burnt out.”

The FBI sounded ideal. But Walder’s experience there was far from it.

“The CIA was an amazing place to be a woman,” she says. “I just assumed that the FBI would be the same. Maybe that was naïve of me. It was pretty terrible from day one. Harassment, sexism — all of that.”

Never one to quit, she stuck it out for 15 months, hoping that things would improve.

When they didn’t, she left the bureau to pursue her original goal of becoming a teacher, joining the Hockaday School in Dallas, an independent K-12 girl’s school and one of the largest single-gender schools in the U.S.

Empowering women and girls

For 10 years she taught AP U.S. History and AP Comparative Government and Politics at Hockaday. She also created “Spycraft,” her highly popular signature course for the senior class, covering domestic and international terrorism and intelligence collection.

In doing so, Walder succeeded in creating her own mini-Farm for young women, many of whom, she says, have gone on to careers at the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the FBI and the CIA.

“In February, I gave a talk at the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., and 15 or 20 of my former students came because they’re all in that field in Washington, D.C., which made me super happy,” Walder says.

Qualities Walder considers essential to be a good spy include an open mind and an excellent ability to read people. To any students considering a career in the intelligence services, Walder advises learning Chinese or Arabic, honing problem-solving skills and securing a CIA internship.

Walder left Hockaday in January and is about to start a new chapter in her life: Next year she will join Texas Christian University where she will teach a course on women in law enforcement.

Tracy Walder teaching at the Hockaday School for girls in Dallas, where she created her highly popular senior class, “Spycraft.”

Walder believes that women bring valuable qualities to intelligence gathering and leadership roles.

“I was reading an article from Mossad, the Israeli intelligence service, and [the writer] said that sometimes women make better spies because we listen differently and we tend to empathize more, and we’re better sensors of people,” she notes.

She also stresses the importance of hearing more women’s voices in foreign policy and foreign affairs. “Not because I think women are better,” she says, “but because I think they’re equal and they bring a different perspective to the table, and we need men and women’s perspectives.”

The importance of international cooperation

Walder is keen to emphasize that, contrary to what many people believe, most terrorist acts in the U.S. are not committed by foreigners, but by Americans.

To bring that point home to her students, Walder added a unit on domestic terrorism to her espionage course, covering attacks such as the Oklahoma City bombing, the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993, and the 1993 siege in Waco, Texas, in which 76 members of the Branch Davidian religious sect and four government agents died.

“Islamophobia comes from the idea that we think terrorism must come from ‘over there,’ when the reality is that in the U.S. more people probably die of domestic terrorism,” Walder says. “By not making domestic terrorism a prosecutable crime in our law, we’re basically validating that terrorism can only be in the Middle East, and that perpetuates Islamophobia.”

Walder is a firm believer in the importance of international cooperation to defeat terrorism.

“It’s essential. Terrorism affects almost every country, not just our country, and if we think that we’re isolated and globalization doesn’t exist, I think we’re sorely mistaken,” she says.

“Terrorists cross our borders all the time, and if we’re not all on the same page about what to do about it, that’s a problem.”