Faculty reflect upon their fathers’ influence on their academic careers

Father’s Day is a time our thoughts turn to our dads, the unique relationship we enjoyed with them as children and the ways they helped make us who we are today. Here, seven USC Dornsife faculty from a wide range of disciplines reflect on their fathers’ influences on their lives and how their dads helped shape and inspire their academic careers.

William Deverell, professor of history, chair of history and director of the USC–Huntington Institute on California and the West, writes about his father, William F. Deverell Sr.

“My father, for whom I am named, is a retired orthopedic surgeon who spent the first 20 years of his medical career as an officer in the United States Air Force. Growing up a military brat, I’ve learned since boyhood, is a little strange and outside the borders of more conventional, civilian life. But my sister and I knew nothing else, so it seemed entirely normal to us.

“I grew up in houses on Air Force bases in Japan, California, and Colorado. They shared a certain “base housing” exterior sameness, even drabness. On the inside, they shared books. Packed bookcases: medical texts, of course, (The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery by the dozens), travel books, biographies, Great American novels, and, always, history.

“My father has always been drawn to history, and he is deeply well read. His books called to me as a kid, and my constant borrowing of them no doubt shaped my life and my thinking for the better. I went off to college thinking I wanted to be a surgeon; I left college knowing I wanted to be a history professor. In no small way, that journey is motivated by the imprint of a father’s curiosity on a son. We share more than a name, and I’m ever grateful for all of it.”

Lanita Jacobs, associate professor of anthropology and American studies and ethnicity, celebrates her stepfather, Jackie L. Stewart Sr., a retired machinist and church pastor.

“I was in the sixth grade when my dad entered my life. He’d recently found God and fell hard for my mom. I eyed him warily; I didn’t know what to make of this recently converted preacher and single-father of five. Soon, his and my family merged and I inherited four sisters, a brother and a new dad —and two more sisters as our family steadily grew. We were a black ‘Brady Bunch’ with no ‘Alice’; I sulked to the point of disrespect.

“Then, I grew to love him. I knew it when, five months into blended familyhood, I dreamt my new dad had died. I remember waking up in a panic and searching to find and hug him. He said, ‘Don’t worry about it Nita. I’m still here.’

“My dad has held me many times since. When my marriage failed and my world unraveled, my dad said two things that righted me: ‘I understand you baby’ and ‘Forgive yourself because God does.’ He saw me in my vulnerability (priceless), loved me, and inspires my classes on the fraught subject of black love and respectability.

“My dad didn’t graduate high school. In the past five years, he’s earned his B.A. and later M.A. at a seminary. I didn’t make it to his most recent graduation for reasons I can’t defend. When I apologized for my absence, he replied, ‘That’s okay. I know you love me.’ And I do. I do. I do. I do.”

Robert Shrum, Carmen H. and Louis Warschaw Chair in Practical Politics and professor of the practice of political science, pays tribute to his father, Clarence Shrum.

“My parents were part of the great westward migration of the 1950s. They left behind a place where my father’s family had lived for nearly two centuries and brought my 6-year-old sister Barbara and me — I was 8 — to the better life of the new America that was California, with its booming growth and perpetual sunshine.

“But there was another reason for the move: No one in my father’s family had ever gone to college and he was determined that Barbara and I would. My mother taught me to read before kindergarten. My father worried that we wouldn’t have a chance to go to the best schools from a small coal town in Western Pennsylvania. So he drove us across the continent in his 1948 Chevy in search of education.

“He and my mom always found the money for the books I yearned to buy — and then for my tuition at Loyola High School. They put off buying a house until I graduated from Georgetown.

“My father — and the wife he adored — made it their life’s work to lift our lives. My dad told me he loved me, but for him that love was not a just a feeling; it was a mission. And he was quietly proud in his 90s of what his children had done — and though he never said it, what he had done for us.

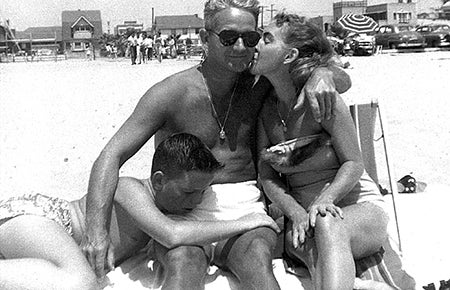

“I often look at a favorite photo, taken on Venice beach soon after we arrived in Culver City. It tells the truth of our relationship far better than any words.”

Megan Luke, assistant professor of art history, on her father, Richard Luke.

“My dad is my first and most avid reader. He reads everything I write (he even read my doctoral dissertation!), and he always understands just what I am trying to do with any given text. My father is a sculptor, a builder and an architect, so he has a high tolerance for art history, but he’s also a passionate self-taught reader of literature and philosophy — and poetry is what he likes reading best. At key moments in my studies, he would introduce me to a writer or an artist and I, in turn, would take up the challenge to write about them.

“Once, when I was in high school, I asked him to read a paper I had written for English class on one of his favorite poets, William Bronk, and he read it as he would a text by any ‘real’ writer. It was the first time my words had received such a demanding audience, and I vividly remember that being the moment when I realized the responsibility that comes with writing — a responsibility to write well and with conviction. To this day, I always begin writing with the aim that the result would be something he would want to read, and the best thing is, he always does.”

James Heft, Alton M. Brooks Professor of Religion, remembers his father, Berl Ramsey Heft, a farmer and warehouse manager.

“My father was a Protestant; I was raised Catholic, the faith of my mother. For the first 36 years of his life, my dad was a farmer; I’ve spent my life in cities. My father never went past the eighth grade; I got a Ph.D. My dad didn’t go to church with me and the rest of the family that often; we went every Sunday and more. My father was 5-foot-8 inches tall; I am 6-foot-5. So, how did my father influence my career as an academic and a Catholic priest?

“Though my father was not Catholic, he was a loving and good man. As a child, I never doubted that he would go to heaven, and as a second-grader in a Catholic school in Cleveland, Ohio, I stood up and spoke out against a teacher who said that only Catholics would go to heaven. Though he had little formal education, he was bright, very bright, and verbally quick. He told great stories. He supported the private education of my four siblings and me. I guess you could say that for much of his life he was deeply spiritual then, but not so religious — ahead of his time.

“He influenced me profoundly even though we might seem to have been very different. Towards the end of his life, shortly after I had told my family what I wanted to do with my life, he became a Catholic. Perhaps I influenced him a little, too.”

Laura Baker, professor of psychology, remembers her father, John P. Baker.

“As long as I can remember, my focus in life has been on figuring out how things work — including people’s behavior. I have to attribute this, at least in part, to my father, who was a civil engineer and a handyman extraordinaire. Early memories include having Dad help me with math homework and visiting his civil engineering office, where I was fascinated by the rooms full of computers, whirring tape decks — and yes, punch card machines — that filled an entire air-conditioned floor of the high-rise building where he worked. There were plenty of opportunities to figure things out on my own, growing up in a house with seven other siblings.

“My father also remodeled his home with his own hands and came to Los Angeles to help me and my husband restore a little Victorian house near USC. As my own research in behavioral genetics shows, Dad’s influence was undoubtedly a combination of genes and environment. Regardless of the etiology, I have my father to thank for my problem-solving skills, and for a determination to get things done and never give up until I am satisfied.”

Alison Dundes Renteln, professor of political science, anthropology, public policy and law, pays tribute to her late father, Alan Dundes, a professor of anthropology and folklore at the University of California, Berkeley.

“My father was a professor for more than 40 years. From him I learned the great joy of exploring libraries, conducting interdisciplinary research, and mentoring students. I also saw the benefits of belonging to a vibrant intellectual community.

“It is important, he often said, to pursue a career one enjoys. He certainly loved his work. A Freudian Folklorist, he believed that the psychoanalytic approach, making the unconscious conscious, could enable us to change our ways.

“Some of the data my father analyzed was difficult, dangerous, and unpleasant. But he was strongly opposed to censorship and considered no topic taboo. When I accompanied him to the former Soviet Union in the early 1970s, and he tried to give out copies of a paper analyzing anti-Soviet jokes, his colleagues were afraid to accept it. This experience sparked my interest in political freedom and human rights, topics on which I continue to focus.

“My father shared his research with influential people to try to contribute to social change. He corresponded, for example, with President Bill Clinton about military policy banning gays and lesbians. From my father, I learned the importance of identifying ethnocentric attitudes, so we can be more compassionate and accepting of people who come from diverse backgrounds. My own research on the legal protection of cultural traditions reflects a commitment to this value. Inspired by my father, I encourage students to reconsider their tacit assumptions, appreciate different points of view, and empower them to use their research to make the world a better place.”