Cells send damaged ‘junk DNA’ to the emergency room for repair

The cell has its own paramedic team and emergency room to aid and repair damaged DNA, a new USC Dornsife study reveals.

The findings are timely, as scientists are delving into the potential of genome editing with the DNA-cutting enzyme CRISPR-Cas9 to treat diseases or to advance scientific knowledge about humans, plants, animals and other organisms, said Irene Chiolo, Gabilan Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences.

Genome editing has arrived before scientists have thoroughly studied the significance and impact of DNA damage and repair on aging and disease, such as cancer. Chiolo’s work has been revealing more about those processes.

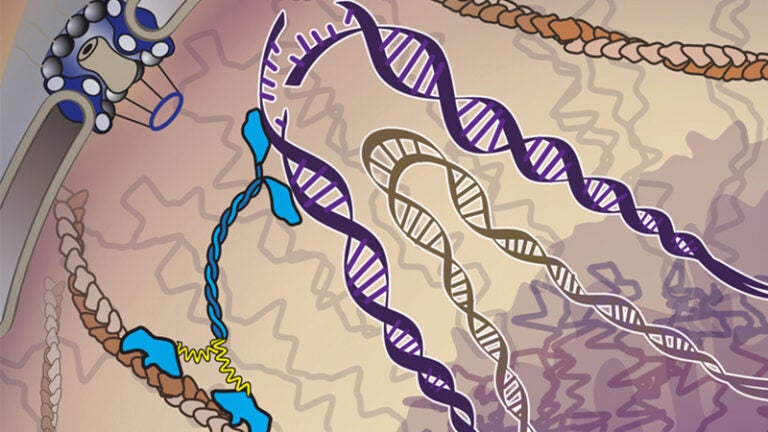

For the study published today in Nature, Chiolo and her team used fluorescent markers to track what happened when DNA was damaged in fruit fly cells and mouse cells. They saw how the cells launch an emergency response to repair broken DNA strands from a type of tightly-packed DNA called heterochromatin.

“Heterochromatin is also referred to as the ‘dark matter of the genome’ because so little is known about it,” said Chiolo. “But DNA damage in heterochromatin is likely a major driving force for cancer formation.”

Don’t call it junk

Repeated DNA sequences have had a bad nickname, “junk DNA,” for about 20 years. Scientists decoding the genome called it junk because they were initially focused on understanding the functions of individual genes.

Since then, studies have shown that repeated DNA sequences are in fact essential for many nuclear activities, but their defective repair is also linked to aging and disease.

“Heterochromatin is mostly composed of repeated DNA sequences,” Chiolo said. “The low gene content is part of the reason why these sequences are less characterized.”

In fact, mutations that compromise heterochromatin repair result in massive chromosome rearrangements affecting the entire genome.

First responders take a walk

The scientists found that after the DNA strands are broken, the cell prompts a series of threads — nuclear actin filaments — to assemble and create a temporary highway to the edge of the nucleus. Then come the paramedics — proteins known as myosins.

“Myosins are conveyed as a walking molecule because they have two legs,” Chiolo said. “One [leg] is attached and the other moves. It’s like a molecular machine that walks along the filaments.”

The myosins pick up the injured DNA, walk along the filament road and then reach the emergency room, a pore at the boundary of the nucleus.

“We knew, based on our prior study, that there was an emergency room — the nuclear pore where the cell fixes its broken DNA strands. Now, we have discovered how the damaged DNA travels there,” Chiolo said. “What we think is happening here is that the damage triggers a defense mechanism that quickly builds the road, the actin filament, while also turning on an ambulance, the myosin.”

The researchers plan further studies examining the repair of DNA in heterochromatin.

“I’m excited to see how the molecular mechanisms we uncovered work in humans, as well as in plants that have much larger heterochromatin. It will be fascinating to see how such a complex repair mechanism functions and evolves over time and what aspects of the mechanisms may be adapted for other functions,” said Christopher Caridi, a co-lead author for the study and a postdoctoral researcher in Chiolo’s lab at USC Dornsife.

About the study

Other study co-authors were Carla D’Agostino (co-lead author), as well as Taehyun Ryu, Grzegorz Zapotoczny, Laetitia Delabaere, Xiao Li, Varandt Y. Khodaverdian, Emily Lin and Alesandra Rau, all at USC Dornsife’s Department of Molecular and Computational Biology. Co-author Nuno Amaral, formerly of the department, is at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden.

The study was supported by a grant from the USC Gold Family and Research Enhancement Fellowships to Taehyun Ryu as well as an NIH R01 grant (GM117376), a Mallinckrodt Foundation Award and a National Science Foundation Career grant (1751197) to Chiolo.